December 11th, 2024 (1st installment: January 21st, 2024).

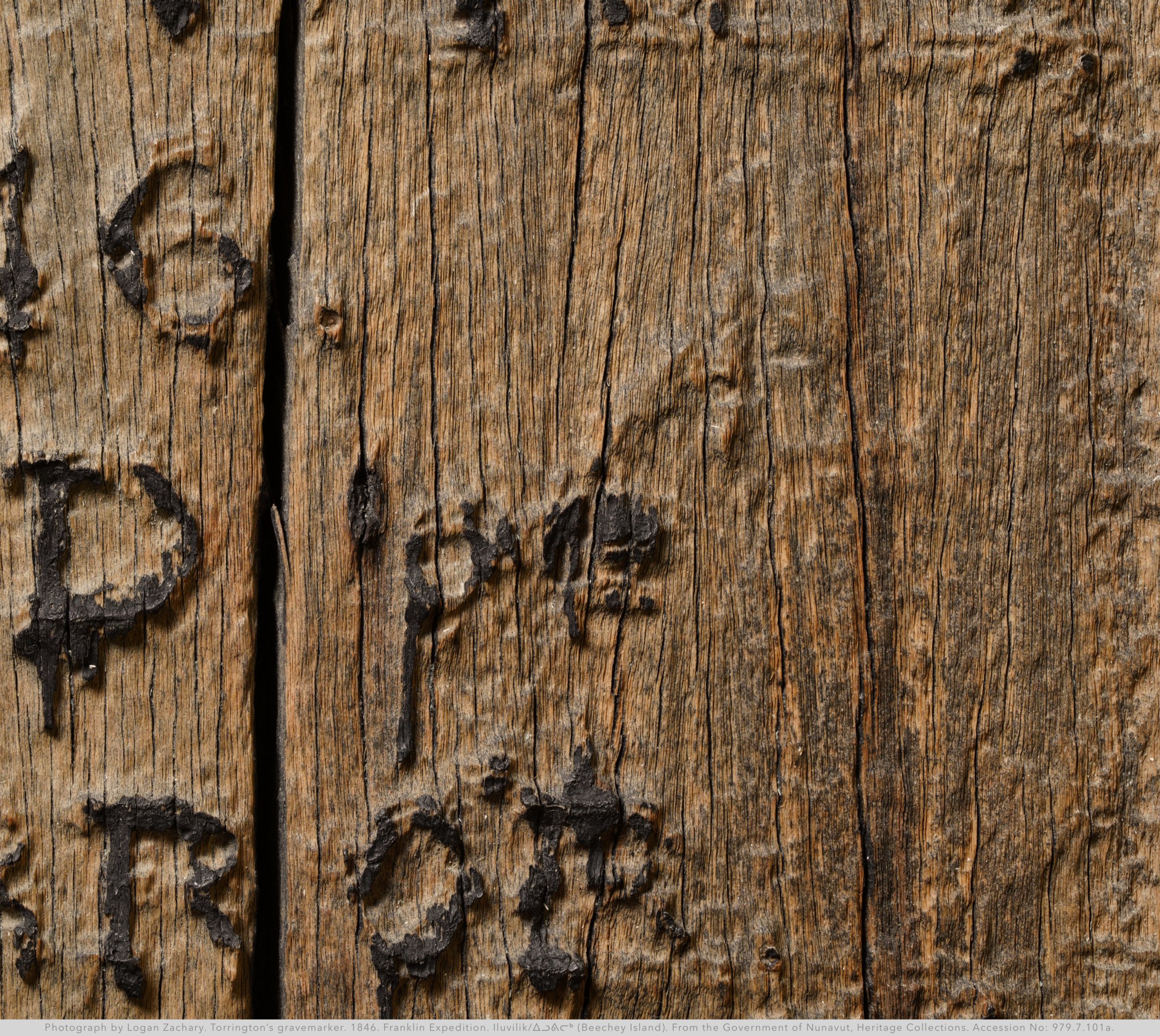

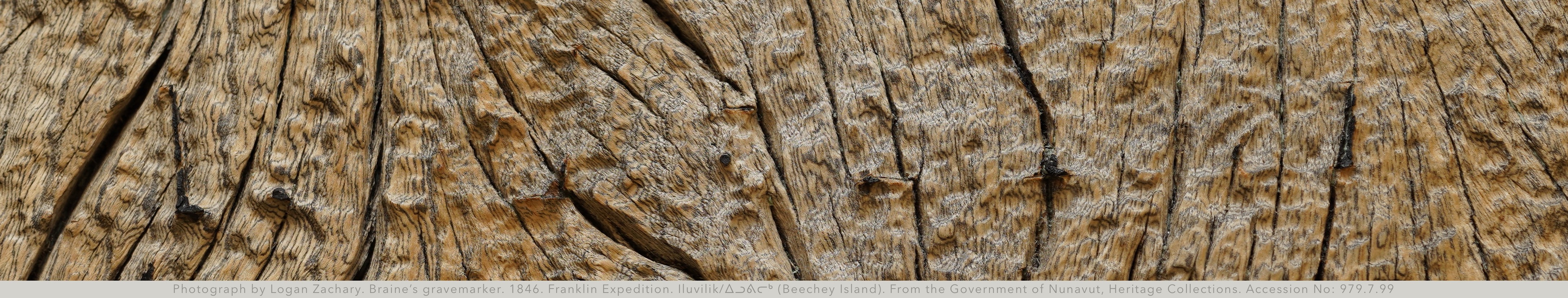

▽ Photographs by Logan Zachary. Braine, Hartnell, & Torrington’s gravemarkers. 1846. Franklin Expedition. Iluvilik/ᐃᓗᕕᓕᒃ (Beechey Island). From the Government of Nunavut, Heritage Collections. Accession Nos: 979.7.99, -.47, -.101a.

Summary: This article demonstrates that the most accurate Beechey gravemarkers transcriber, not previously recognized, was Peter Cormac Sutherland. Anyone understandably dubious of new gravemarker transcriptions coming in 2024 should in future be quoting from and citing Sutherland. However, additional analysis of the Derbyshire graves photograph and the surviving wooden gravemarkers in Canada suggests further refinement of Sutherland’s work.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Transcriptions.Introduction.Sutherland.Hartnell.Torrington.Braine.Select Conclusions.Acknowledgements.Appendices.Bibliography.

The 1st installment of this article (Sutherland and Hartnell) was published on January 21st, 2024. The 2nd and final installment of this article (Torrington and Braine) was published on December 11th, 2024.

TRANSCRIPTIONS.

Note on punctuation: The transcriptions below only present punctuation that we saw some evidence for (with one exception, noted for Braine). The early transcribers of the 1850s all added their own novel punctuation for publishing clarity; likewise, no modern writer should feel prohibited from doing so here.

John Torrington’s gravemarker inscription:

SACRED

TO

THE MEMORY OF

JOHN TORRINGTON,

WHO DEPARTED

THIS

LIFE JANUARY 1st

AD.1846,

ON BOARD of

H·M·SHIP TERROR,

AGED 20 YEARS

Without line breaks: SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF JOHN TORRINGTON, WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE JANUARY 1st AD.1846, ON BOARD of H·M·SHIP TERROR, AGED 20 YEARS

If supported in publishing (the gravemarker inscription), the ordinal suffix of “1st” should be written in superscript, underlined and with two dots beneath.

John Torrington’s coffin plate inscription:

JOHN

TORRINGTON

DIED

JANUARY 1ST

1846

AGED

20 YEARS

Without line breaks: JOHN TORRINGTON DIED JANUARY 1ST 1846 AGED 20 YEARS

If supported in publishing (the coffin plate inscription):

1. The ordinal suffix of “1st” should be written in superscript, underlined and possibly with a dot or two beneath.

2. The first letter of each word in “JOHN TORRINGTON” should be larger in size, effectively using a small caps font.

John Hartnell’s gravemarker inscription:

SACRED

to the

MEMORY OF

JOHN HARTNELL

AB OF H.M.S *

EREBUS

died January 4th 1846 *

Aged 25 years *

Haggai C1. V7.

Thus saith the Lord of hosts

Consider your ways. *

Without line breaks: SACRED to the MEMORY OF JOHN HARTNELL AB OF H.M.S. * EREBUS died January 4th 1846 * Aged 25 years * Haggai C1. V7. Thus saith the Lord of hosts Consider your ways. *

Four asterisks have been added to mark the unidentified symbols in the inscription, and may be removed according to taste.

If supported in publishing:

1. The ordinal suffix of “4th” should likely be written in superscript.

2. The first letter of each word in “JOHN HARTNELL” should be larger in size, effectively using a small caps font.

John Hartnell’s coffin plate inscription:

Unknown — missing. Taken by Edward Augustus Inglefield in 1852. It is hoped that the coffin plate may still survive with one of his descendants today.

William Braine’s gravemarker inscription:

SACRED

to the

MEMORY

of

W. BRAINE : R.M.

H.M.S. EREBUS,

Died April 3rd 1846

Aged 32 Years

Choose you this day whom ye will serve

Joshua C24 Part of the 15V

Without line breaks: SACRED to the MEMORY of W. BRAINE : R.M. H.M.S. EREBUS, Died April 3rd 1846 Aged 32 Years Choose you this day whom ye will serve. Joshua C24 Part of the 15V

If supported in publishing (the gravemarker inscription):

1. The ordinal suffix of “3rd” should be written in superscript.

2. The first letters of the words “SACRED”, “MEMORY”, and “W. BRAINE” should be larger in size, effectively using a small caps font.

For publishing clarity, in the version without line breaks, we have placed a period after “serve,” to avoid the misleading appearance that “Joshua” is being addressed. Sutherland (and most other transcribers) placed punctuation there as well.

William Braine’s coffin plate inscription:

W. BRAINE

R.M. 8 CO. W.D

H.M.S. EREBUS

DIED APRIL 3RD 1846

AGED

33

YEARS

Without line breaks: W. BRAINE R.M. 8 CO. W.D H.M.S. EREBUS DIED APRIL 3RD 1846 AGED 33 YEARS

If supported in publishing (the coffin plate inscription), the ordinal suffix of “3rd” should be written in superscript. If additional accuracy is desired, the letter “d” of that ordinal suffix should be in lowercase, with the letter “R” as a small capital. If maximum accuracy is desired, the figure “4” in “1846” should be horizontally reversed.

INTRODUCTION.

“...the still, quiet desolation of all around me was unbroken, save by... the loud beating of my heart and quick-drawn breathing, ere I could gather courage to advance and read the inscriptions...”— Robert A. Goodsir, at the discovery of the Beechey graves.

{ ▽ “HM SHIP.” Torrington’s gravemarker. }

“Sacred to the memory of John Torrington.” “Consider your ways.” “Choose ye this day whom ye will serve.” The inscriptions from the Beechey Island gravemarkers are some of the most oft-repeated and instantly recognizable phrases in the history of the Franklin Expedition. And little wonder: with so little paper ever recovered from the lost expedition, these gravemarker inscriptions represent a significant proportion of what writing has survived — lengthier than the first entry on the Victory Point Record.

For example, they happen to tell us where leading stoker John Torrington died: “on board HMS Terror”.

Or, was it written as “on board of HMS Terror”? Or was it written “on board of HM Ship Terror”?

In fact, depending on who you consult, all of the above phrasings are correct. Because despite the prominence and continued repetition of these gravemarker inscriptions, there has never been any consensus on their exact wording. The substance of the inscriptions isn’t in question, but the spellings and even minor word choices become debatable as one looks closer. For Braine’s Bible verse alone, there are four wording variations to choose from.

You may return to primary sources, the first accounts of the 1850–51 searchers who discovered Franklin’s winter camp and its graveyard. But there you are confronted with the problem of deciding which one of those early gravemarker transcribers to trust.

{ ▽ Some early gravemarker transcribers: Kane, Markham, Osborn. }

Cyriax used Osborn’s transcriptions. The modern replacement gravemarkers use Kane. The most recent scholarship recommends McDougall. And this study will advance another: Sutherland.

The issue is further confused by nearly all historians not citing which transcription they are presenting — and further, by mixing in their own custom alterations. Beattie & Geiger’s landmark Frozen In Time appears to have utilized Kane leavened with Osborn, but does not comment on the decision. Even the great Cyriax altered his usage of Osborn’s transcriptions, with modifications as frivolous as writing out “25” as “twenty-five” (Hartnell’s age).

It was only after three bodies had been raised, autopsied, and reburied on Beechey Island that researchers began to articulate a much simpler question: What, precisely, was the nature and history of the above-ground memorials on the island? This seemingly straightforward query has engendered a half dozen research articles since 1993 (Hobson), with the most recent coming in 2017 (Hansen).

Even then, the spotlight did not swing towards the Franklin inscriptions themselves until 2010. In that year, researcher Todd Hansen had published an article analyzing the Beechey Island memorials in Polar Record. Then, later that October, Hansen did something novel: he wrote back to Polar Record and changed his mind. Hansen switched his evaluation of the most authoritative gravemarker transcriber from Kane to McDougall:

“...comparison of the inscriptions with both Kane and the photo of the Torrington headboard in Powell now lead me to conclude that McDougall’s rather than Kane’s version of the Franklin headboards inscriptions are probably the most accurate of the contemporary accounts.”[Hansen 2012.]

To the present authors’ knowledge, this was the first example of published comparative analysis of the Beechey gravemarker transcriptions. Nor did Hansen stop there. For his following article, Hansen travelled to a Government of Nunavut archive in Yellowknife for the next logical step: to attempt to bring the original gravemarkers into his analysis.

{ ▽ Photograph from Allen Young’s 1875 Pandora expedition. }

One would initially think that these wooden tablets might be ‘the last word’ on the subject. But though removed from Beechey Island for preservation in the 1970s, the original wooden gravemarkers are today significantly weathered and worn. They endured over a century exposed to the Arctic climate and Arctic fauna (a searcher in 1852 reported a huge polar bear “continually sitting on one of the graves”), with questionable re-paintings and possibly re-carvings of their vanishing inscriptions by later visitors.

Nonetheless, wielding “a flashlight at a shallow angle,” in 2016 Hansen was able to discern enough to correct two words in McDougall’s transcriptions, and to demonstrate a flaw in Kane’s transcriptions. Hansen’s new findings were published in 2017. But rather than the first of such attempts, in a way Hansen’s would be the lone example of its kind, completed just before a significant shift in the landscape. Just two years later, a paramount new source would come to light, found on the other side of the planet from Beechey Island.

In the English Midlands, in the county of Derbyshire, sits the county town of Matlock. Here at the county’s record office resides a collection of Franklin family possessions, bequeathed by the descendants of Franklin’s daughter Eleanor. In 2019, Assistant Conservator Clare Mosley at the Derbyshire Record Office recognized something of significance in one of the Franklin scrapbooks: a very early photograph of the Beechey Island gravemarkers — with their inscriptions visible.

{ ▽ Derbyshire Record Office, D8760/F/LIB/10/1/1. }

Mosley had the photograph published online through the Derbyshire Record Office, and it immediately became the subject of a Russell Potter article at Visions of the North (Potter 2019b). Potter dwelt in particular on the photograph’s upending of modern visualizations of the gravemarkers, as being either white-painted or bare wood. In the Derbyshire photograph, the gravemarkers appear black against the lighter rocks of the island’s shore — just as sources close to the discovery had reported they were.

The door was thus open for a new evaluation of the Beechey gravemarker inscriptions, repeating Hansen’s attempt to decipher the original gravemarkers in person, but now with the Derbyshire photograph as a map to the missing words. For this study, the present authors have travelled to Canada and Britain, interviewed Claire Mosley in Matlock about her discovery, and watched as Flora Davidson removed the protective travel packaging from the original gravemarkers currently held outside Ottawa — unstudied since Hansen’s initial effort over half a decade earlier. Like Hansen, our analysis has been observational only: as practiced whilst searching for Northwest Passage graves in London’s Kensal Green Cemetery, we employed nothing more technical than “a flashlight at a shallow angle.”

SUTHERLAND.

{ Markham’s private journal, making several errors. }

At first glance, the Derbyshire photograph is so revealing, one wonders if this exercise might most resemble the correcting of written exams. The Derbyshire schoolmaster calls each of the early gravemarker transcribers forward, holding their works aloft before the class, every mistake in turn rapped crisply with the pointing rod.

Some of what follows resembles just that. But the exam results need to be addressed here, before proceeding. They do not show that sometimes we must listen to Kane, and other times to Osborn; that Markham’s version of Hartnell is best, but that McDougall should be consulted for Torrington, etc. The results reveal something different: a star pupil.

{ Peter Cormac Sutherland (1822-1900). }

For each gravemarker, we assembled the best transcriptions we could find. In each contest, it came down to a single word, a photo finish. And yet each time, the laurel wreath went to the same person, a name we hadn’t ever seen preferred before: Peter Cormac Sutherland.

Looking at his biographical details, such a conclusion might have been guessed at sooner. Sutherland wasn’t Royal Navy. He was a physician, a geologist, a naturalist, a surveyor — in short, someone trained to observe the world just as it is. His book alone presents his Beechey graves transcriptions in situ: written onto their respective gravemarkers, the graves in the correct left-to-right order, mounds of rock circling their bases. His “transcript” even records that two posts held up Braine’s gravemarker — a detail missed in the scene sketch by Sutherland’s closest transcriptions rival, the artist McDougall.

{ ▽ Sutherland’s published journal. }

{ ▽ Sutherland’s gravemarker transcriptions. }

{ ▽ McDougall’s scene sketch, Illustrated London News, 4 Oct 1851. }

{ Note no posts beneath Braine’s gravemarker. }

Sutherland was surgeon on the Sophia during the big 1850–51 Franklin search, meaning that he was present on the morning that the Beechey graves were discovered. He was then 28 years old. He came back for another Franklin search the following year, as surgeon on the Isabel. Though not a familiar name, most eyes reading these words will have seen Sutherland walk across the stage of this story before. In Beattie & Geiger’s classic Frozen In Time, the authors highlight that one surgeon had wished to conduct an exhumation of the Beechey graves immediately, on the same 1850–51 search that had discovered them. That surgeon was Peter Cormac Sutherland.

And when Hartnell’s grave was exhumed in the 1980s, Owen Beattie and his team discovered that Hartnell had in fact already been exhumed, by someone in the past. Their research later revealed that Captain Inglefield of the Isabel had ordered a quiet midnight exhumation of Hartnell in 1852. The man at Inglefield’s side for that exhumation, his ship’s surgeon, was Peter Cormac Sutherland — fulfilling his wish from his previous search.

Thus we already know Peter Sutherland, as the early advocate of exhuming the graves on Beechey Island, as well as the surgeon at the actual exhumation of Hartnell in 1852. To this, we can now add that Peter Sutherland was also the most authoritative transcriber of the Beechey gravemarker inscriptions.

But how much authority is he due? What happens in a situation where Sutherland, the Derbyshire photograph, and the surviving gravemarkers are in disagreement with one another?

Conversely, how much weight can we place on those other two sources? Despite stretches of legibility, neither the Derbyshire photograph nor the surviving wooden gravemarkers present an unobstructed read through the inscriptions. Consider also that we do not know if the surviving gravemarkers are showing us the letters as originally carved, or if later visitors found it necessary to re-carve them at some point. The black-painted letters on them today are certainly later work, commonly attributed to Bernier’s visit in 1906. Similarly, we do not know precisely when the Derbyshire photograph was taken. Does it show us the gravemarkers as they were originally found in 1850? Or does it show them after T.C. Pullen’s repainting of the gravemarkers (SPRI GB15) in 1853? Or later? And did any alterations creep in to Pullen’s repainting? The photograph in Derbyshire was found tipped in amidst newspaper articles from 1851, which is certainly suggestive, though not enough for a conclusive dating. In that photograph, are we seeing paintwork that looks crisp and fresh? Or does it look like it just survived half a decade (1846–50) exposed to Arctic weather? The former seems more plausible, and we do know that Beechey Island photography without snow on the ground was taken during the Belcher search (Wamsley & Barr 1996).

{ ▽ Elisha Kent Kane at the graves (Wellcome Collection, 1858). }

This study cannot address these questions at the outset. It will proceed attempting to balance the weight of all three sources: the surviving gravemarkers currently held outside Ottawa, the photograph in Derbyshire, and the works of the early gravemarker transcribers, led by Peter Sutherland.

As a forecast for the sections that follow: Hartnell will prove complex but manageable, Torrington will be brief to deal with, and then Braine is where significant issues arise.

HARTNELL.

{ Hartnell’s gravemarker, the Derbyshire photograph. Edited for clarity. }

The biggest visual shock of the Derbyshire photograph arguably wasn’t the jet-black coats of paint, which in fact had been recorded in multiple early sources. What was completely unexpected, left unremarked in every known description and illustration of the graves, was sitting atop Hartnell’s inscription.

A decorative element. A tree.

{ Hartnell’s gravemarker, decoration detail. }

Or is it a tree? The “trunk” appears split at the base — as if it is in fact two branches, crossed above the letter “R” in “SACRED”.

John Hartnell was not alone on the expedition: his brother Thomas Hartnell was with him on board HMS Erebus, both as Able Seamen. If this symbol is two branches crossed, they most likely symbolize the two brothers.

It is also notable that the gravemarker’s bright border line seems to widen significantly – on both sides – just above where the branches approach it (see arrows on image below). This intimation of moving beyond the gravemarker’s edge raises another possibility: that this is a portrayal of the bottom curve of a wreath. The laurel wreath as a symbol commonly shows two branches crossed at its base.

{ Hartnell’s gravemarker, widened border line marked by arrows. }

The wreath is classically a symbol of victory. While we are unaware of any episode in John Hartnell’s life to warrant such a symbol, it is also notable that we know nothing about the final six months of his life as an individual. Nor would his be the only Franklin Expedition gravemarker with a laurel wreath. The gravemarker later built for HMS Terror’s John Irving in Edinburgh features a laurel wreath with crossed branches — symbolizing 2nd place in a summer mathematics competition in Greenwich (see Zachary 2020 for photography).

Of perhaps particular relevance is the gravemarker of HMS Resolute’s George Malcolm on nearby Griffith Island, which features a small crossed-branches wreath near the top. Malcolm died on the same 1850-51 search that had discovered the graves, and thus the Resolute’s men created this design after having recently seen Hartnell’s gravemarker.

[Note the shallow groove along the edge in these photos, presumably where the bright border line was painted.]

They may have been intended to balance the centering of the lines. But if so, then it is unusual that the 6th line of the inscription (“EREBUS”) did not receive one, as it is centered too far to the left. [Unless, of course, we are seeing later paintwork which missed it. We looked for a trace in the wood, but saw nothing conclusive. Nor would we necessarily, if it had been lost so early on.]

TORRINGTON.

And here is the word photographed with a raking light:

By casting a raking light from one side, we can illuminate a previously hidden ridge on the gravemarker, matching the long swooping letter “f” from the Derbyshire photograph. And it indeed reaches down and touches the word “TERROR” beneath it.

Regarding punctuation, the environment that we started with from Hartnell is reversed: Torrington’s punctuation is almost impossible to see in the Derbyshire photograph, yet is starkly visible on the surviving wooden gravemarker. Whether a comma or a dot or a period, a similar punched or drilled hole seems to have marked each, and is readily apparent in the wood today: no continuous grain lines run through their centers, and they feature a slight reddish discoloration around their edges.

In line 8, “AD 1846,” all early transcribers put a period between “A” and “D”. But the gravemarker shows not a hint of a mark in that location, nor any space to have ever included one. Meanwhile the two other punctuation marks in the line are unambiguous.

At “H.M. SHIP”, the two punctuation marks accompanying “HM” are seen to be distinctly centered dots raised above the baseline, as in a Latin inscription, and not mere abbreviation periods. No transcriber, early or modern, previously recorded this detail.

Working backwards, it is possible to assign the final cluster of letters to “will serve” (see below), with the taller ascender strokes of the double lowercase letters “LL” hazily suggested. This allows previous shapes in the line to be discerned as “whom ye”, with the taller ascender stroke of the letter “h” suggested — and a fairly distinct “ye”, not “you”, identifiable.

However, across that line, there are clusters of very small horizontal cuts – not half the width of your fingernail – with nothing apparent connecting them.

From that same highlighted section above, consider the following discrete area.

The position of “day” is clear, and the position of the letters “hi” in “this”. But here we reach the most bizarre observation contained in this study. Earlier in this section, when examining the Derbyshire photograph, we had commented that: “...the position for “this” rather looks like a word beginning with a capital letter “C”.” Such a letter was so out of place, we dropped the photograph and turned to the surviving gravemarker to try to explain it. Now the serif marks have carried us to that same position on the gravemarker. And there, in the wood itself, we can observe... a prominent knot, also resembling a capital letter “C” (see above for clarity, see below for position and comparison).

This potential letter “u” lines up well with the Derbyshire photograph. In the image below, the arrow marking the potential letter “u” is in precisely the same position over the wood as in the image above. From that position, it does indeed mark where the first pronoun had ended in Derbyshire’s photograph.

Focusing our attention on the date of death, we see precisely what the Derbyshire photograph had indicated: a half-height numeral “3” with a superscript notation above it.

The image below isolates the superscript figures at high resolution. [Inside the cracks of the wood are light blue elements, presumably artifacts from when casts of the Franklin gravemarkers were made in the 1970s.]

Like Torrington, Braine’s coffin plate inscription is noticeably a reduced version of his gravemarker inscription (see comparison below). Unlike Torrington, there is one significant addition of information. After “R.M.”, for “Royal Marine”, the 2nd line of Braine’s coffin plate adds “8CO.W.D”, for “8th Company, Woolwich Division” (Lloyd-Jones 2004).

How did Braine’s coffin plate render the date of death? It is written “3rd” — but with an odd twist.

BRAINE 3 of 3: The Bible verse citation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.

{ ▽ Malcolm’s gravemarker, wreath detail. }

Malcolm’s gravemarker. 1851. Franklin search expedition, 1850–51. Qikiqtaaluk/ᕿᑭᖅᑖᓗᒃ (Griffith Island). From the Government of Nunavut, Heritage Collections. Accession No: 979.95.1.

{ ▽ Malcolm’s gravemarker, inscription detail. }

What is most unusual about Hartnell’s branches is that, while the left branch stretches out and upward, part of the right branch seems to slump back down into the word “SACRED”. Why is it not symmetrical? Or, are the branches indeed symmetrical, and we are in fact seeing additional figures above the “ED” in “SACRED”? Could they be letters? If so, they have escaped every transcription of Hartnell’s gravemarker, and this would seem unlikely.

Given these questions, a search for traces of this decorative element was a priority for our inspection of the original gravemarker. However we found no significant remnants of the “crossed branches” decoration. There is a faint line that matches well with the position of the upward curve of the right branch; this was the only trace we felt confident in identifying as likely having been a part of the lost decoration.

{ Hartnell’s gravemarker. Photograph by Alison Freebairn. }

[Note the shallow groove along the edge in these photos, presumably where the bright border line was painted.]

{ GIF of Hartnell’s gravemarker, Derbyshire juxtaposed with today. }

{ ▽ Hartnell’s gravemarker, tree/branches area. }

It is possible that the crossed branches decoration was never carved quite as deeply as the lettering, or perhaps never re-carved back into the wood by later visitors to the island. Or, perhaps it was only painted on, never carved in — however, other lettering on the gravemarker has been equally worn to this degree. For now, the Derbyshire photograph remains the most effective way of studying this decoration, despite the questions it leaves unanswered.

As a decorative element, the crossed branches are not alone on Hartnell’s gravemarker. They join an unusual number of decorations that Hartnell alone received, whilst Torrington and Braine did not.

Two survive prominently. A line (with curves at each end) is still depicted on the gravemarker, the lower remnant of what Derbyshire’s photograph shows us was once a full border line closing in the inscription. As well, though all three Franklin gravemarkers feature a similar sloped top, Hartnell’s alone has additional pointed peaks near the base of the slope, resembling horns or ears on the gravemarker. Hansen’s physical descriptions of the gravemarkers (2017) leaves this detail unremarked; nor did we notice them in person, only spotting the unique feature in our photography after having left Canada. However, Hartnell’s “ears” have not been forgotten. They were faithfully maintained for the 1993 replacement gravemarkers on Beechey Island. Despite the almost uniform modern design employed, they make Hartnell’s instantly recognizable: once you see them, you never fail to notice them again.

{ ▽ Hartnell’s gravemarker: “ears” shown by arrows. }

{ Russell Potter’s photograph of Hartnell’s replacement gravemarker, 2004. }

{ Russell Potter’s photograph of Hartnell’s replacement gravemarker, 2004. }

The final decorative element of Hartnell’s gravemarker is only discoverable when one works through the inscription in the Derbyshire photograph. Four of the lines seem to close with unknown extra characters, unrelated to the wording. We do not know what they are or what their function is.

One characteristic that some and perhaps all of them have in common: they slant to the right.

{ Hartnell’s gravemarker: four extra characters marked. }

They may have been intended to balance the centering of the lines. But if so, then it is unusual that the 6th line of the inscription (“EREBUS”) did not receive one, as it is centered too far to the left. [Unless, of course, we are seeing later paintwork which missed it. We looked for a trace in the wood, but saw nothing conclusive. Nor would we necessarily, if it had been lost so early on.]

{ ▽ “...C1 V7”; “...Lord of hosts”; “...ways.*” }

{ One unidentified mark is just after “ways.” }

{ ▽ Detail of unknown mark, end of line 11. }

Unfortunately, like the crossed branches, our study of the original gravemarker only found traces of these marks — not enough for us to determine what they are. The best preserved seemed to be the mark in the final line, closing the inscription (image above).

The most compelling proposal was made later in 2019, when researcher Natalie Martz created a physical mock-up of the gravemarkers. In this work, Martz was the first to suggest that what looked like a tree may instead be crossed branches — and, that the extra characters in the inscription may be decorative leaves, matching the theme from the branches at the top. Building off Martz’s thematic idea, a similar possibility is acorns; the plinth of Franklin’s memorial statue in Waterloo Place, London, for example, is ringed by acorns and oak leaves in bronze.

Perhaps their greatest significance today is to suggest that, where they survive, we are seeing original 1846 inscription carving. For if someone in the past had decided that the inscription was so faint as to need to be re-carved into the wood, there would be a natural tendency to neglect fading figures with no apparent connection to the wording of the inscription.

Whatever these four symbols in the inscription are, they were apparently never remarked upon or recorded in contemporary descriptions. Their positions will be represented in our transcription by asterisks.

Distinguishing these marks is necessary to working through Hartnell’s inscription. However, having listed the new decorative elements revealed by the Derbyshire photograph, it is worth a short digression to analyze their significance.

From what we knew before, it was Hartnell and Braine’s graves that received a greater level of attention, whilst Torrington’s was more spartan. The obvious explanation is that Torrington was from Terror, whilst the other two were from Erebus, and this must simply have been how their respective carpenters and crew went about memorializing a shipmate. Frozen In Time makes this distinction in regard to the design of the larger rocks placed on the graves (chapter: “The Face of Death”; cf. McCormick 1884), but it equally applies to the gravemarkers. Furthermore, Torrington died first, and therefore the novelties we see with Hartnell and Braine – custom Bible verses and three-piece gravemarker constructions – might also be viewed as a natural inflation of design elements.

But now the further decorations we see in the Derbyshire photograph, lavished on Hartnell alone, have muddled these rationales. Hartnell had died second, not last. Yet when Braine dies four months after Hartnell, the Erebus carpenters only give him a simplified, reduced version of Hartnell’s gravemarker. Gone are the crossed branches, the decorative marks inside the inscription, the bright border line around it all, the extra pointed peaks atop the gravemarker. Though he did receive a Bible verse, Braine’s lone painted decoration is a short line at the bottom of his inscription, resembling a moustache in shape. This is more reminiscent of Torrington, not Hartnell, with his simple flat diamond shape closing his inscription.

{ ▽ Derbyshire Record Office, D8760/F/LIB/10/1/1. }

What was the reason for this? Why was more effort put into Hartnell’s gravemarker, a matter of mere days after Torrington’s? And why then did these same Erebus ship carpenters put significantly less effort into Braine’s gravemarker?

The obvious reason would be that John Hartnell’s brother Thomas was present.

However, was Thomas Hartnell himself even still alive when John Hartnell died? An almost universal assumption has been that: because only three graves were found on Beechey Island, therefore only three men died in the first year of the Franklin Expedition (Cyriax 1939). But Beechey Island is hundreds of miles past where whalers last encountered Franklin’s ships. Someone could have died and been buried anywhere on the shores of Lancaster Sound and Barrow Strait, their gravemarker erased by ice or animals long before ever being found (as has potentially happened with any Franklin Expedition graveyard on King William Island). Or perhaps men were lost into the water, as the searcher Bellot would later be in Wellington Channel. Curiously, John Hartnell was buried wearing a shirt that bore two red embroidered figures resembling his brother’s initials: “TH”. One possible explanation is that: John had Thomas’ shirt on because Thomas was no longer alive.

But reversing the question here is illustrative: Would this much extra effort be put into John Hartnell’s gravemarker, if his brother Thomas wasn’t alive and present for the burial? This would seem to be the significance of what the photograph is showing us. While it is circumstantial evidence, we suggest that the higher level of decoration revealed by the Derbyshire photograph may be read as an indication that Thomas Hartnell had indeed survived the first year of the Franklin Expedition.

Returning to the gravemarker then, with all decorative elements identified, and the four unknown marks within the text put aside, we can begin to work through the inscription itself.

In Derbyshire’s photograph, the third line from the bottom has a fairly distinct “C1 V7”, after a word starting with “H”. This would be the citation for Hartnell’s Bible verse: the Book of Haggai, chapter 1 verse 7, written as “Haggai C1. V7.”

{ Hartnell’s gravemarker, last lines of inscription. }

We can use this line to sort out which transcribers failed to record the Bible citation correctly: Kane and Osborn, who both moved it down to the final line and removed the letters “C” and “V” (see graphic below).

As well, Kane’s attempt at showing the proper line breaks for Hartnell was more misleading than helpful. Osborn, meanwhile, does not even attempt to record the original line breaks. But Osborn accurately transcribes Hartnell’s death date, “died January 4th, 1846” — a line which Kane misses entirely.

{ The Hartnell transcriptions compared. }

McDougall and Markham do not make these mistakes. They correctly put the Bible citation ahead of the Bible verse, and do a far better job at delineating where the line breaks are. Still, on this last point, they do make some deviations — and they both write “Jan. 4” for the death date, when it is discernible in the Derbyshire photograph that “January 4th” was written out, unabbreviated and with the two-letter ordinal suffix.

The Illustrated Arctic News’ transcription is more accurate than all of these. A shipboard newspaper published on board HMS Resolute during the 1850–51 search (with Osborn and McDougall as its editors), its superior gravemarker transcriptions appeared in the first issue, October 31st, 1850. Every line break is in the correct position, at which point its only competitor is Sutherland. But it abbreviates “January” to “Jan.y”, its lone deviation — and thus Sutherland’s transcription, by one word, appears as the most accurate for Hartnell’s gravemarker. He has every word, every letter, and every line break just as we see them in the Derbyshire photograph.

Not that Sutherland doesn’t have deviations. However he only does so – as we will see repeatedly with him – regarding letter case and punctuation, not wording and spelling. For the Hartnell inscription, in six of eleven lines Sutherland deviates on letter case. Admittedly, this still puts him closer to the Derbyshire photograph’s letter case scheme than any other transcriber. He even does a fairly faithful replication of the changing glyph sizes from one line to the next — something no other transcriber attempted to record.

But which source should we prioritize? What if the Derbyshire photograph is showing us a later repainted inscription, after alterations had crept in? If so, then Sutherland should have priority.

And here the argument might have deadlocked. Yet there is one more source to consult.

{ The Derbyshire photograph vs. today. }

At just a glance, one can understand why this task was neglected for so long. The aging wooden gravemarker appears to have reduced John Hartnell’s complex inscription to just eight words: SACRED – MEMORY OF – JOHN HARTNEL – OF HMS – EREBUS.

But when one looks closer, it gets worse. Initially we can discern a rough similarity of the letter positions. But in the line “AB OF H.M.S”, the letters “HMS” noticeably occupy different positions today than they did in the Derbyshire photograph (see below). Where once they covered the space beneath the letters “ARTNE” in “HARTNELL”, they now fit entirely beneath “ART”.

{ “HMS” comparison, Derbyshire vs. today. }

Thus we have an example of today’s black-painted letters not merely being absent, but marking novel positions.

However, unlike all modern attempts to read these gravemarkers, we now have the Derbyshire photograph to guide us as a map. In 2017, Hansen had noted that “AB” was missing on the surviving gravemarker. He speculated that perhaps “OF” had originally been “AB”. But he also noted that space was available for “AB” to have been located off to the left. The Derbyshire photograph shows us that the latter was indeed the case — and that now, knowing where to look, the faint impressions of a nearly vanished “AB” can still be discerned.

{ ▽ Remnants of “AB” location. }

Thus, with the Derbyshire photograph as a guide, the remains of otherwise vanished letters can still be found — whilst the black painted letters are shown, in the “HMS” example, to at times be significantly unfaithful to the past inscription.

Another example is right in the line above: “JOHN HARTNELL”. In Hansen’s 2016 in-person study of the gravemarkers, he commented that there simply wasn’t space available for a second “L” after HARTNEL-. In the Derbyshire photograph, we can see that a second “L” was indeed present — but that Hansen’s observation wasn’t inaccurate, as that 2nd “L” was squeezed very tightly against the border line.

Using a light source from the left on the original gravemarker, in March 2023 we were able to make the faint depression of the 2nd “L” reappear, despite some significantly ridged grain lines.

{ The missing 2nd “L” of HARTNELL. }

This 2nd “L” noticeably lacks any black paint. And here it is interesting to consider a much later transcription. In 1904, A. P. Low visited Beechey Island in the Neptune. In a cairn note he left on the island (Bernier 1909), he included a transcription of impressive accuracy, ignoring line breaks but otherwise matching Sutherland and the Derbyshire photograph word-for-word on Hartnell’s inscription. With one exception: Bernier records Low spelling Hartnell with only one “L”.

We believe all of these observations fit together. They demonstrate the possibility that the faint depression of a missing letter on the wooden gravemarker may still be found, even when it was otherwise considered invisible – and apparently ceased to be painted in – more than a century in the past.

And here – after these same letters “LL” which we see pressed tightly against the edge – Sutherland’s transcription would tell us that a comma then closed the line. Yet we see a carving of the letters that contradicts Sutherland and corroborates the Derbyshire photograph: there is no room left for closing punctuation between “LL” and where the border line would have lain. Indeed, it is so tight that Low/Bernier and Hansen would drop the 2nd “L”.

In general, Sutherland appears to have been profligate with punctuation, as were the other transcribers. For example, in the Derbyshire photograph, we see only two periods in “H.M.S”, whilst not a single transcriber resisted adding a third period to properly close the abbreviation. However, other than this one unusual circumstance after “JOHN HARTNELL”, the deterioration of the wood makes it too subjective to try to identify punctuation – or a lack thereof – on the surviving wooden gravemarker.

If punctuation were the only dispute to be measured, this would leave us with just one instance on which to judge Sutherland vs. the Derbyshire photograph. But turning to letter case, several more comparisons can be drawn.

{ ▽ Detail showing “SACRED” in uppercase. }

Two letter case disputes are readily visible. Sutherland wrote “Sacred” for the inscription’s first line, but the surviving gravemarker confirms the Derbyshire photograph’s rendition as “SACRED”, all uppercase. Then at the Bible verse, where Sutherland wrote “Hosts”, the surviving letter carving confirms the Derbyshire photograph’s version as “hosts”, all lowercase.

At which point, all remaining letter case disputes are in lines that are missing: that Hansen in 2017 reported as unreadable.

Again the Derbyshire photograph can be followed as a map. At the otherwise lost Bible citation line, we can identify the edges of the word “Haggai,” followed by a capitalized “C1. V7.” — contradicting Sutherland’s lowercase rendering. As well, though most of line 8 (“Aged 25 years”) is indeed gone, we can find the distinct remains of the word “years” at its end — and it is lowercase, again contradicting Sutherland.

{ ▽ Hartnell, remnants of lines highlighted. }

{ The Derbyshire photograph. }

{ ▽ Hartnell, remnants of lines highlighted. }

In sum, Sutherland deviates six times from the Derbyshire photograph regarding letter case. In four of those six, we are still able to read the surviving wooden gravemarker. Each time, the surviving gravemarker agrees with the Derbyshire photograph, contradicting Sutherland. Furthermore: on this question of letter case, all surviving letters on the gravemarker are a match for the Derbyshire photograph. There are no deviations between the two.

With that perfect agreement on letter case, as well as Sutherland appearing to be overruled in the one instance where we can check his punctuation against the wooden gravemarker (line 4: “JOHN HARTNELL,”), we believe that such agreement between the Derbyshire photograph and the surviving gravemarker should have priority over Sutherland.

This suggests a new transcription for John Hartnell’s gravemarker: to follow the perfect agreement of the Derbyshire photograph, the surviving gravemarker, and Peter Sutherland regarding words, spellings, and line breaks, but then to prioritize the first two sources regarding letter case and punctuation. That formula results in the following alterations to Sutherland’s 1852 transcription.

Letter case changes from Sutherland:

Line 1, from “Sacred” to “SACRED”.

Line 2, from “TO THE” to “to the”.

Line 7, from “Died” to “died”.

Line 8, from “AGED 25 YEARS” to “Aged 25 years”.

Line 9, from “c. I. v. 7.” to “C1. V7.”

Line 10, from “Hosts” to “hosts”.

Sutherland’s punctuation where confirmed by the Derbyshire photograph:

Line 5, two abbreviation periods in “H.M.S”.

Line 9, two periods in “C1. V7.”

Line 11, period following “Consider your ways.”

New Hartnell gravemarker transcription:

SACRED

to the

MEMORY OF

JOHN HARTNELL

AB OF H.M.S *

EREBUS

died January 4th 1846 *

Aged 25 years *

Haggai C1. V7.

Thus saith the Lord of hosts

Consider your ways. *

{ New Hartnell transcription, 2024. }

Without line breaks: SACRED to the MEMORY OF JOHN HARTNELL AB OF H.M.S. * EREBUS died January 4th 1846 * Aged 25 years * Haggai C1. V7. Thus saith the Lord of hosts Consider your ways. *

Asterisks have been added to mark the unidentified symbols in the inscription.

If supported in publishing:

1. The ordinal suffix of “4th” should likely be written in superscript.

2. The first letter of each word in “JOHN HARTNELL” should be larger in size, effectively using a small caps font.

End of 1st installment, January 21st, 2024.

Start of 2nd installment, December 11th, 2024.

TORRINGTON.

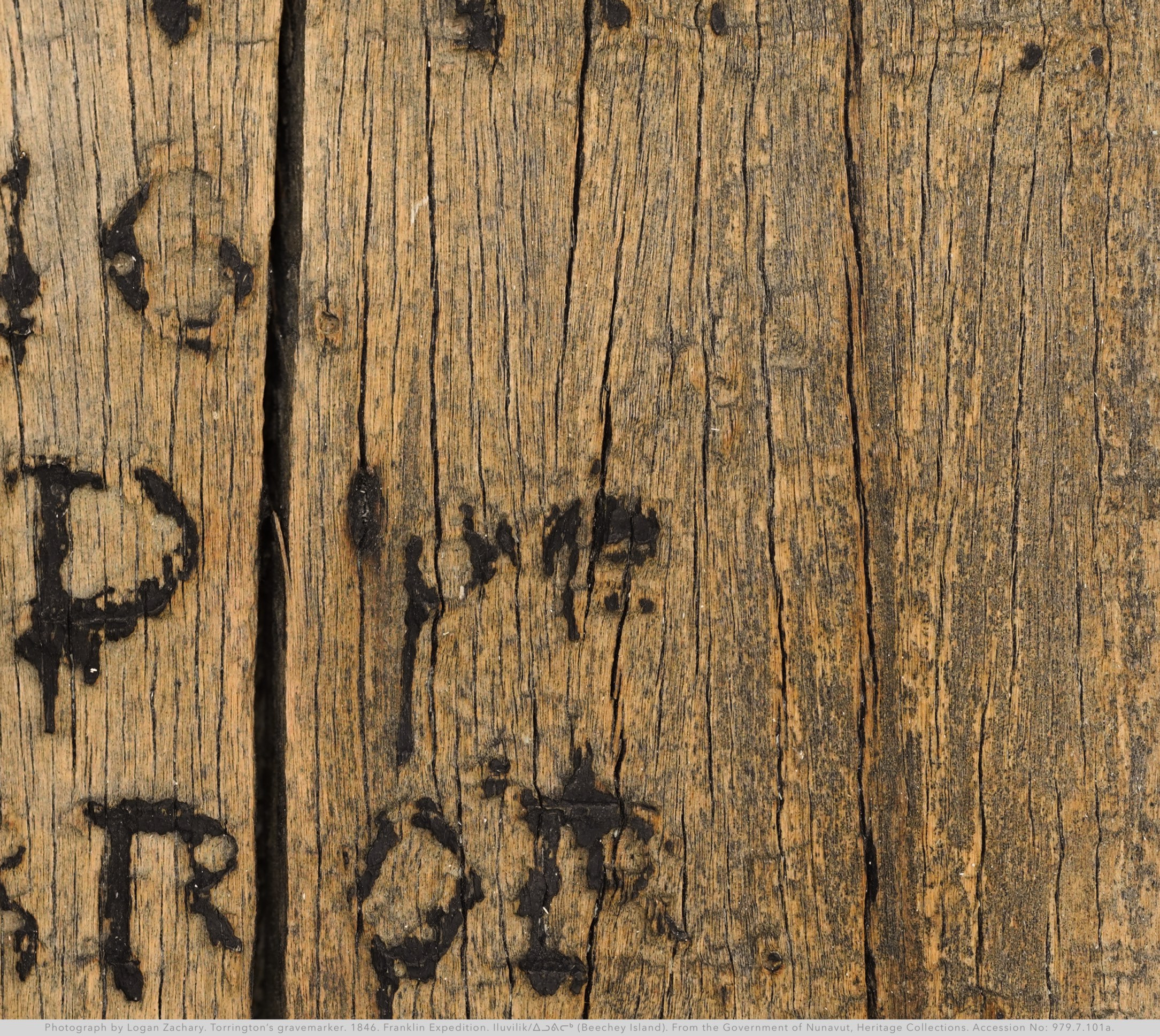

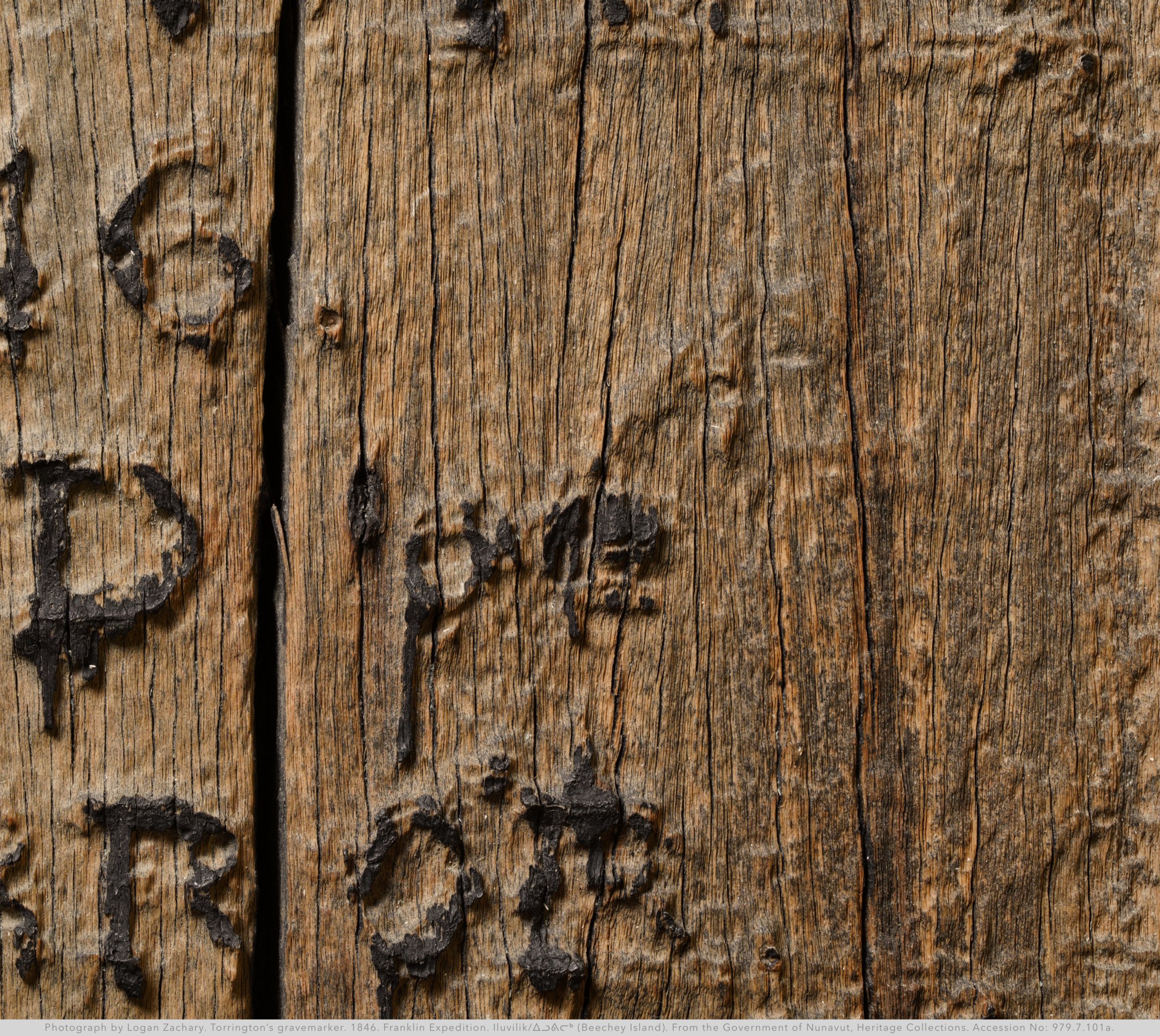

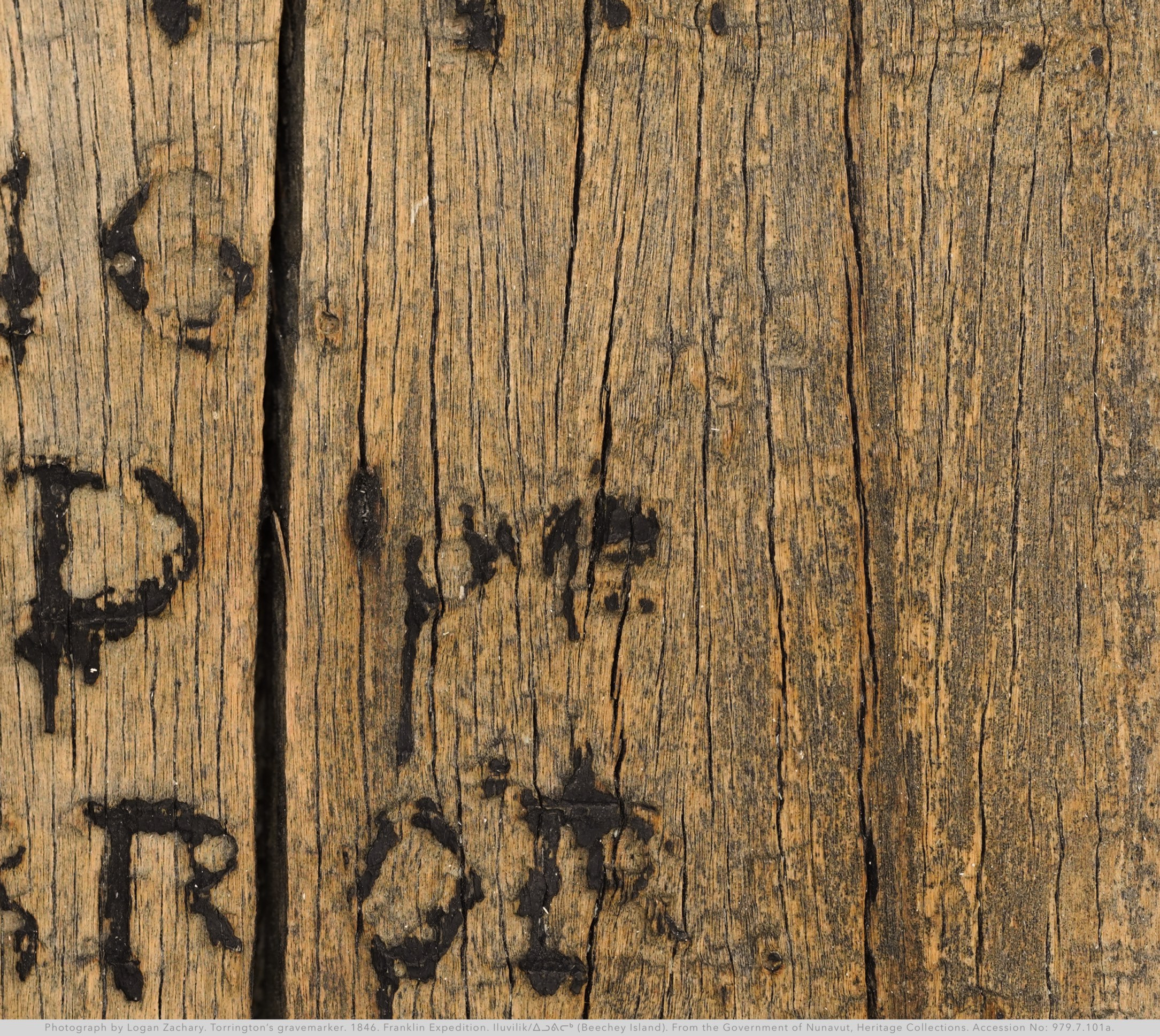

{ Torrington’s gravemarker. }

In the Derbyshire photograph, Torrington’s inscription is less legible than Braine’s or Hartnell’s, as his gravemarker was situated furthest from the camera’s lens.

But by a fortunate coincidence, Torrington’s surviving gravemarker is today the most legible of the three, and by a wide margin.

{ ▽ Torrington’s surviving gravemarker; Ottawa, 2024. }

This legibility has meant that, prior to the discovery of the Derbyshire photograph, Torrington’s surviving gravemarker was the only yardstick by which to measure the early transcribers.

Kane benefited unfairly from this. For despite his significant errors with Braine and Hartnell, Kane got every word of Torrington’s inscription correct — a feat unequalled here by Osborn, Markham, M’Dougall, and even The Illustrated Arctic News (all of whom stumbled at minimum on “HM SHIP”). This likely led to the preference for Kane, e.g. in Beattie & Geiger’s Frozen In Time (1987), in Powell’s 2006 paper on Beechey Island memorials, and on the current replacement gravemarkers standing on Beechey Island today.

{ Russell Potter’s photography of Torrington’s replacement gravemarker, 2004. }

{ The Torrington transcriptions compared. }

But one transcriber bettered Kane. While they match each other word for word, Kane makes several line break errors, while Sutherland continues to pitch a perfect game in this regard.

From this example alone, Sutherland might have been recognized decades ago as the preeminent Beechey gravemarkers transcriber. Kane – now that we can hold the rest of his work up against the Derbyshire photograph – turns out not to have been even in the top three of the early transcribers.

{ ▽ Torrington inscriptions triptych. }

Turning to letter case, we find the same situation that we saw with Hartnell: where Sutherland deviates, the surviving gravemarker and the Derbyshire photograph appear to be in agreement with each other, contradicting him. Sutherland writes “Life January” in line 7, while the surviving gravemarker shows “LIFE JANUARY”. Consulting the Derbyshire photograph – otherwise nearly unreadable here – indicates a match for the wooden gravemarker’s uppercase rendition, not Sutherland’s title case.

Indeed, Torrington’s inscription is almost entirely in uppercase. Sutherland himself doesn’t suggest lowercase letters outside of lines 1 & 7. What about the surviving gravemarker and the Derbyshire photograph? Do they suggest lowercase letters anywhere at all?

The answer to this minor point – Where are the lowercase letters? – turns out to have a bearing on larger questions regarding the gravemarkers.

In a 2006 paper for Polar Record, researcher Brian Powell raised the question of whether the surviving wooden gravemarkers held in Canada are the authentic originals, i.e., the gravemarkers created by the Franklin Expedition itself. He thus cautiously referred to today’s surviving gravemarkers throughout his paper as “the presumed originals.” It is an unsettling question to have posed, for three blocks of wood that went largely unobserved in the Arctic for more than a century.

Even a decade later, Hansen’s 2017 paper would devote most of its “General Discussion” section to answering Powell’s question of authenticity. Today, after 2019, just a glance at the Derbyshire photograph is enough to have reasonable confidence that Braine and Hartnell, with their more complex gravemarker constructions, are a match for what survives in the Government of Nunavut’s storage. Torrington’s, however, is different. It consists of only a single upright board, whose shape could have been conceivably replicated with little more effort than mimicking the slope along its top.

{ Torrington’s raised lettering. }

Examining the inscription magnifies the problem. In a striking difference from Hartnell and Braine, the lettering on the Torrington gravemarker is today consistently protruding up from the wood, not carved down into it. And while this could simply be different weathering characteristics due to the type of wood used (interacting with paint in the grooves to better protect the letters from wear), it is not the most concerning issue.

That most concerning issue is simply that Torrington’s inscription has by far the least complex typography of the three. It therefore would have been the easiest Franklin gravemarker for someone in the past to have made a convincing replica of, and thus taken the original away as a souvenir. [And this, then, would be a ready explanation for Torrington’s unusual raised lettering and overall excellent condition.]

In sum, when we consider Powell’s question of authenticity, suspicion falls heaviest on Torrington’s gravemarker. It has the least complex gravemarker design, the least complex typography, the least deteriorated inscription — and the most unusual weathering characteristics for that inscription. [Not incidentally, it also exhibits the most unusual paintwork changes in historical Beechey photography, leading us years ago to refer to it as “the David Bowie of Beechey gravemarkers.”]

With all of these issues, how can we be certain that we are not looking at a well-crafted replica?

The Derbyshire photograph has revealed one unusual twist in the typography of the inscription, which may answer Powell’s question of authenticity for Torrington’s gravemarker.

{ Lines 8, 9 & 10. }

Torrington’s inscription tells us that he died “on board of HM Ship Terror,” with the words “on board of” set into a single line.

But that word “of” on the gravemarker does not resemble the word “of.”

{ Apostrophe “pe”...? }

We only know this word as “of” from the early transcribers. The final letter looks like an “e”. And indeed, a recent on-camera reading of the gravemarker’s inscription mistook this word as “the.” Interestingly, that is how A.P. Low had recorded the word as long ago as 1904: “ON BOARD THE HMS TERROR.”

However, nearly all the gravemarker transcribers of the 1850s recorded this little word as “of” (it is also the more grammatically correct reading, given the meaning of “H.M.S.”).

With the Derbyshire photograph, we can now observe how this word was originally written.

{ Derbyshire photograph vs. 2024. }

It is revealed to have been fairly unusual: it appears as the only lowercase word in the entire inscription — and with a long swooping stroke for the letter “f”. Indeed, the swoop of the stroke seems to reach down to touch the word “TERROR” in the next line.

Finally, taking this bit of knowledge back to the surviving gravemarker, we can look past the daub of black paint for the remains of the original letter.

Here is the word photographed in direct light:

{ ▽ Direct light. }

And here is the word photographed with a raking light:

{ ▽ Raking light. }

By casting a raking light from one side, we can illuminate a previously hidden ridge on the gravemarker, matching the long swooping letter “f” from the Derbyshire photograph. And it indeed reaches down and touches the word “TERROR” beneath it.

{ The Derbyshire photograph. }

{ Left: Derbyshire photograph superimposed over the gravemarker. }

{ Right: raking light illumination of the lost letter. }

This is a critical survival. It could only have been identified now, with the Derbyshire photograph as a map pointing us to it. When would this letter have last been seen? The fact that the letter was apparently missed as early as 1904 (when Low recorded this word as “the”) would cordon off the 20th century, as well as some amount of time prior to 1904 as the letter began to fade.

We suggest that this is now the best answer to Powell’s question of authenticity regarding Torrington’s gravemarker: with the remains of that ridge still present – while also being hidden for at least 50 years, possibly more than 120 years – Torrington’s surviving wooden gravemarker has a claim to being as old as the Derbyshire photograph itself.

Returning to the analysis of the transcriptions: Which, then, of the early transcribers faithfully preserved the style of this word “of”? None. Sutherland, otherwise the most accurate transcriber, published this word “of” in uppercase letters.

Thus, regarding Torrington’s letter case, the situation that we saw with Hartnell has been repeated. In all four disputed instances that we can compare – “SACRED”, “LIFE”, “JANUARY”, and “of” – the surviving gravemarker and the Derbyshire photograph are in agreement with each other, contradicting Sutherland.

{ Torrington punctuation examples. }

Regarding punctuation, the environment that we started with from Hartnell is reversed: Torrington’s punctuation is almost impossible to see in the Derbyshire photograph, yet is starkly visible on the surviving wooden gravemarker. Whether a comma or a dot or a period, a similar punched or drilled hole seems to have marked each, and is readily apparent in the wood today: no continuous grain lines run through their centers, and they feature a slight reddish discoloration around their edges.

{ “AD.1846.” punctuation. }

In line 8, “AD 1846,” all early transcribers put a period between “A” and “D”. But the gravemarker shows not a hint of a mark in that location, nor any space to have ever included one. Meanwhile the two other punctuation marks in the line are unambiguous.

{ ▽ Overview of Torrington’s closing lines. }

{ ▽ H·M·SHIP. }

At “H.M. SHIP”, the two punctuation marks accompanying “HM” are seen to be distinctly centered dots raised above the baseline, as in a Latin inscription, and not mere abbreviation periods. No transcriber, early or modern, previously recorded this detail.

Further in this same line is something else unusual: there appears to be punctuation after the word “SHIP”.

A comparison to other Torrington punctuation reveals this mark to be unusually superficial: it is the only mark shallow enough to fully observe the grain lines running through it.

The inverse of the previous situation is found at the very end of the inscription, closing line 11. All of the early transcribers placed a period here. However the characteristic circular mark seen elsewhere on the gravemarker is nowhere evident. [A nearby example of one is just above, at the close of line 10, a mark which Sutherland and others agreed was a comma.]

We looked for a trace of the diamond shape on the surviving wooden gravemarker, but found no indication of carving. [This lends weight to the possibility that Hartnell’s “crossed branches” were only painted on, never carved in.]

{ ▽ Faint mark after “SHIP” in line 10. }

A comparison to other Torrington punctuation reveals this mark to be unusually superficial: it is the only mark shallow enough to fully observe the grain lines running through it.

{ Punctuation marks in Line 10; one more superficial than the others. }

How is this mark to be assessed? Recovering overlooked details such as this was precisely the point of this study. And yet to include this mark as punctuation requires then overlooking its unusually shallow and superficial nature — as well as the fact that none of the reliable early transcribers recorded punctuation here. Nor would a period or comma existing here serve any grammatical purpose.

Our assessment is that, while a mark was certainly made into the wood here, it was presumably made in error. No such mark is discernible in the Derbyshire photograph, and perhaps it was never painted in. We suggest that while a wooden replica of the gravemarker ought to retain this mark, a typed transcription ought to omit it.

{ ▽ Ends of lines 10 & 11. }

The inverse of the previous situation is found at the very end of the inscription, closing line 11. All of the early transcribers placed a period here. However the characteristic circular mark seen elsewhere on the gravemarker is nowhere evident. [A nearby example of one is just above, at the close of line 10, a mark which Sutherland and others agreed was a comma.]

{ ▽ Detail of the end of line 11. }

But there does appear to have been some kind of mark at the end of line 11 — perhaps one that was only ever painted on. This is, also, one of only two places in the Derbyshire photograph where Torrington’s punctuation appears to be visible; however, it could just as easily be mere photographic noise.

Like the previous example after “H·M·SHIP”, our transcription will omit recording punctuation here, while flagging the ambiguity of the evidence left in both of these locations.

Having reached this point, only one substantial question remains unresolved from Torrington’s inscription: the date of death. Specifically, how the date of death was written.

John Torrington died on New Year’s Day, 1846. Almost all the early gravemarker transcribers recorded that date as January “1st”, including Sutherland. However, Hansen in 2017 noted that the death date on the gravemarker appears as if it is written as January “18”. He suggested that the strange “8” symbol could be accidental blackening from Bernier’s repainting, or less likely a weathered “st”.

In 2019, working from Hansen’s verbal description and a low resolution photograph, we suggested two other possibilities (RtFE 2019). The “8” figure may be only the first letter of an “ST” suffix (with the following letter “T” lost to wear), or even a superscript ring (as “1º”), signifying an ordinal number in countries such as Italy.

The following new photography shows what survives today, in 2024, at much higher resolution than has been available before.

{ ▽ The general area of the date of death. }

{ ▽ Torrington’s date of death. }

What is this strange symbol? It is certainly more than accidental blackening. Nor is it a letter “S”.

There is a discernible horizontal line drawn through the middle. This would suggest superscript writing above. Was that superscript notation an “ST”, or an ordinal ring? It is disconcerting how much it resembles a bit of both.

There is something else present here: beneath the horizontal line, there are two circular marks. They resemble the marks made for punctuation throughout Torrington’s inscription.

{ ▽ Two marks below the line. }

These particular marks are distinctly raised above the baseline.

A dot is sometimes placed beneath a superscript notation, as seen in examples on the Victory Point Record. Sometimes two dots are used. The American searcher Edwin De Haven (captain of Kane’s ship the Advance) twice recorded the death date from Torrington’s gravemarker in this manner: a superscript “st”, underlined, with two dots beneath [TNA ADM 7/192; USNA MS 211].

{ Underlines and double dots: one of De Haven’s handwritten graves transcriptions. }

{ Photograph by Alison Freebairn. TNA ADM 7/192. }

Considering the presence of the horizontal line and two dots, we believe there is sufficient evidence to conclude that Torrington’s death date was written with a superscript notation. Such a notation would most likely have been an “st” suffix, even if the carving is effectively unreadable on the gravemarker today.

However before closing this point, there is one final source to consult. These gravemarkers were not the only written memorials left on Beechey Island by the Franklin Expedition: hidden beneath the ground, each sailor was buried with a coffin plate inscription.

We could not consult this source for Hartnell. His coffin plate was taken away and lost in the 19th century (Beattie & Geiger 1987). But Torrington’s coffin plate had survived beneath the ground on Beechey Island. It was photographed in 1984 by Owen Beattie.

{ ▽ Torrington’s coffin plate, 1984. Photograph courtesy of Owen Beattie. }

The first observation to make is that there are a number of decorative elements here, in particular around the word “DIED”, but also at line 5 and after line 7.

This is surprising, as the Derbyshire photograph revealed that only a flat diamond shape had decorated Torrington’s gravemarker (and as the coffin plate would likely never be seen again). It raises the question as to how Hartnell’s missing coffin plate may have been decorated, as his above-ground grave and gravemarker received so much more attention than Torrington’s. [William Braine’s coffin plate is decorated only by a border line.]

{ ▽ Decorations comparison, gravemarker and coffin plate. }

We looked for a trace of the diamond shape on the surviving wooden gravemarker, but found no indication of carving. [This lends weight to the possibility that Hartnell’s “crossed branches” were only painted on, never carved in.]

{ ▽ Derbyshire photograph superimposed (left) to indicate the diamond’s position. }

The wording of the inscription on Torrington’s coffin plate is essentially a reduced version of what we saw on his gravemarker. The only novelty is that the phrase “departed this life” is simplified to “died”.

It is entirely possible and even likely that whoever composed the gravemarker inscription also composed the coffin plate inscription — and, that the same carpenter and crewmen from HMS Terror created both. Therefore, it is relevant to observe how the death date of New Year’s Day was written on the coffin plate.

{ The date of death line. }

{ The date of death. }

While most of Torrington’s coffin plate inscription is in excellent condition, there is significant corrosion on the right half. However, enough survives at the date of death to discern a horizontal line, again suggesting a superscript notation. A small mark, perhaps a dot, is visible just beneath the line. Above the line, there appear to be two characters. In particular, the lower half of a letter “s” seems to be visible on the left.

And so while the death date here has significantly deteriorated, the remains corroborate what we saw on the wooden gravemarker: the suggestion of a superscript notation, and that most likely being “st”.

That suffix is what nearly all the early gravemarker transcribers recorded, including Sutherland. Whether the letters were carved as uppercase or lowercase letters is beyond our reach. However, all early transcribers who recorded “st” did so in lowercase.

This final issue, the writing of Torrington’s date of death, had the potential to catch Sutherland making his first spelling error. But with the weight of evidence pointing towards “st”, Sutherland appears to have again faithfully recorded all words, spellings, and line breaks. And yet as we saw with Hartnell, Sutherland again has deviations regarding letter case and punctuation. In all four instances where Sutherland deviates on letter case (SACRED, LIFE, JANUARY, of), the Derbyshire photograph corroborates the surviving gravemarker, contradicting Sutherland. Regarding punctuation, the Derbyshire photograph is fuzzy, but the surviving gravemarker is surprisingly clear on where punctuation was and was not used: three times Sutherland is contradicted (lines 7, 8, & 11), and once his work is modified (line 10, “H.M.” to “H·M·”).

These observations suggest the identical conclusion that we reached with Hartnell: to follow the perfect agreement of the Derbyshire photograph, the surviving gravemarker, and Peter Sutherland regarding words, spellings, and line breaks, but then to prioritize the first two sources regarding letter case and punctuation. That formula results in the following alterations to Sutherland's 1852 transcription for Torrington.

Letter case changes from Sutherland:

Line 1, from “Sacred” to “SACRED”.

Line 7, from “Life January” to “LIFE JANUARY”.

Line 9, from “OF” to “of”.

Sutherland’s punctuation where confirmed by the surviving gravemarker:

Line 4, comma after “JOHN TORRINGTON”.

Line 8, period after “AD”, comma after “1846”.

Line 10, comma after “TERROR”, periods at “H.M.” raised to centered dots.

New Torrington gravemarker transcription:

SACRED

TO

THE MEMORY OF

JOHN TORRINGTON,

WHO DEPARTED

THIS

LIFE JANUARY 1st

AD.1846,

ON BOARD of

H·M·SHIP TERROR,

AGED 20 YEARS

Without line breaks: SACRED TO THE MEMORY OF JOHN TORRINGTON, WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE JANUARY 1st AD.1846, ON BOARD of H·M·SHIP TERROR, AGED 20 YEARS

If supported in publishing (the gravemarker inscription), the ordinal suffix of “1st” should be written in superscript, underlined and with two dots beneath.

Torrington’s coffin plate inscription:

JOHN

TORRINGTON

DIED

JANUARY 1ST

1846

AGED

20 YEARS

Without line breaks: JOHN TORRINGTON DIED JANUARY 1ST 1846 AGED 20 YEARS

If supported in publishing (the coffin plate inscription):

1. The ordinal suffix of “1st” should be written in superscript, underlined and possibly with a dot or two beneath.

2. The first letter of each word in “JOHN TORRINGTON” should be larger in size, effectively using a small caps font.

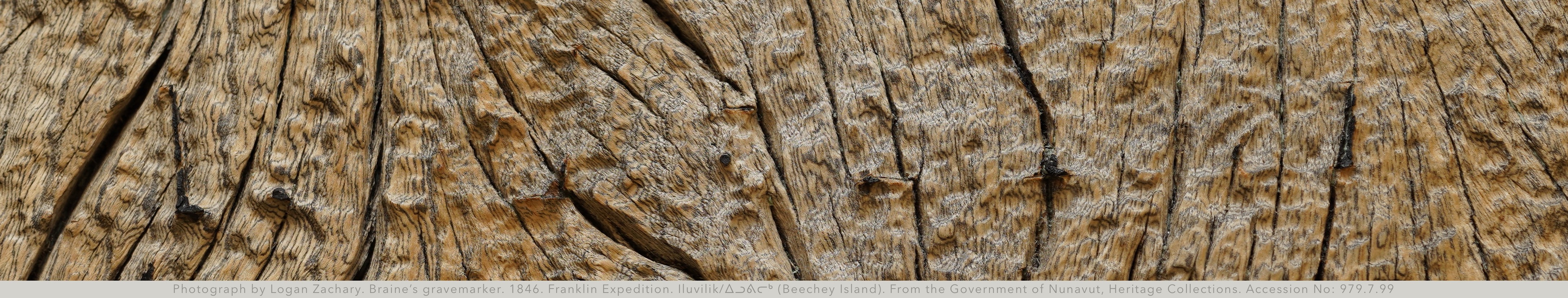

BRAINE.

“3D”. A curious detail from the replacement gravemarkers on Beechey Island today is that William Braine did not die on “April 3rd,” but on “April 3D.”

Answering these and other questions regarding Braine’s inscription is daunting. Even compared to Hartnell, Braine’s wooden gravemarker is today in the worst condition of the three. While Hartnell’s has merely worn down (and Torrington’s is still largely readable), Braine’s gravemarker has significantly split along the wood grains. Looking up close for Braine’s vanishing inscription today resembles searching for patterns across a mountain range, a range regularly broken by black chasms to the center of the planet.

Making matters worse, when we turn to Derbyshire, about a fifth of Braine’s inscription disappears off the left edge of the photograph. And yet: all of the contentious issues regarding the inscription do appear on the portion that is still visible to us.

Due to that missing edge, we cannot see how William Braine’s first name was rendered. But everyone except Osborn tells us that it was simply “W.” The surviving gravemarker bears this out. [The abbreviation period is no longer entirely clear, however we do assume one was there given the significant character sizes, as well as the Derbyshire photograph showing other prominent punctuation marks in this same line.]

The early transcribers disagreed with each other the most at the last two lines of Braine’s inscription: the Bible verse and its unusual citation. Given this disagreement, it is therefore the best place to begin evaluating their transcriptions.

{ Russell Potter’s photograph of Braine’s replacement gravemarker, 2004. }

Many a modern visitor to Beechey Island has probably consulted their copy of Frozen In Time, and discovered that this “3D” is not a typo, but rather a delightfully strict adherence to the original inscription.

Or is it? Is “3D” correct? Some early transcribers of Braine’s inscription wrote “3rd”, not “3D”. Which did the original inscription use?

{ ▽ Braine’s surviving gravemarker; Ottawa, 2024. }

Answering these and other questions regarding Braine’s inscription is daunting. Even compared to Hartnell, Braine’s wooden gravemarker is today in the worst condition of the three. While Hartnell’s has merely worn down (and Torrington’s is still largely readable), Braine’s gravemarker has significantly split along the wood grains. Looking up close for Braine’s vanishing inscription today resembles searching for patterns across a mountain range, a range regularly broken by black chasms to the center of the planet.

{ ▽ The letters “-u th-” are technically present here (line 9). }

Making matters worse, when we turn to Derbyshire, about a fifth of Braine’s inscription disappears off the left edge of the photograph. And yet: all of the contentious issues regarding the inscription do appear on the portion that is still visible to us.

{ Braine’s gravemarker in the Derbyshire photograph. }

Due to that missing edge, we cannot see how William Braine’s first name was rendered. But everyone except Osborn tells us that it was simply “W.” The surviving gravemarker bears this out. [The abbreviation period is no longer entirely clear, however we do assume one was there given the significant character sizes, as well as the Derbyshire photograph showing other prominent punctuation marks in this same line.]

{ “W. Braine” (line 5). }

{ The Braine transcriptions compared. }

The early transcribers disagreed with each other the most at the last two lines of Braine’s inscription: the Bible verse and its unusual citation. Given this disagreement, it is therefore the best place to begin evaluating their transcriptions.

BRAINE 1 of 3: The Bible verse pronouns.

“Choose ye this day whom ye will serve.” The Bible verse from Braine’s gravemarker is familiar from any short history of the Franklin Expedition.

But how was it written? Was it, “Choose YE this day whom YE will serve”? Or was it rather, “Choose YOU this day whom YOU will serve”? Were these two pronouns “you,” or “ye” — or a combination of both?

Remarkably, the early transcribers collectively offer us every possible combination.

ye/ye – Sutherland.ye/ye – Kane.ye/ye – Osborn.you/you – Austin.you/you – Markham’s book.you/ye – McDougall.you/ye – The Illustrated Arctic News.ye/you – De Haven.

The Sutherland transcription tells us that the Bible verse was squeezed entirely into a single line of Braine’s inscription (on this point, Kane concurs). Unfortunately, that line of Braine’s inscription isn’t readily legible in the Derbyshire photograph.

{ Line 9 highlighted. }

Working backwards, it is possible to assign the final cluster of letters to “will serve” (see below), with the taller ascender strokes of the double lowercase letters “LL” hazily suggested. This allows previous shapes in the line to be discerned as “whom ye”, with the taller ascender stroke of the letter “h” suggested — and a fairly distinct “ye”, not “you”, identifiable.

{ Line 9 word proposals. }

However, continuing to work backwards, “day” is less distinct. Worse, the position for “this” rather looks like a word beginning with a capital letter “C” — at which point, one is left wondering if any of these tentative word assignments are correct.

Here, we would hope to be able to turn to the original wooden gravemarker for a third opinion.

But in 2017, while Hansen identified the remains of this line, he concluded that “no letters are readable.” Attempting to use the Derbyshire photograph as a map, in 2023 we were only able to improve on that assessment with a single word: from the closing “...whom ye will serve”, the word “will” is still just discernible when a raking light is cast across it.

{ ▽ The remains of “will” (line 9). }

The letters are faint, but they are in the correct position indicated by the Derbyshire photograph (just down diagonally from the last letter of the word “Years” in the line above).

Having exhausted what a flashlight at a shallow angle could do, even with the aid of the Derbyshire photograph, we believed the search was over. However, months after having left Canada, in the summer of 2023 we found in our photographs a new method for reading the Beechey gravemarkers.

{ Letters written with (black) and without (red) serifs. }

{ Serifs marked in red. }

A serif is an extra flourish to a letter, a small extra mark at the end of a primary stroke. Not all typefaces have serifs, but it is evident from the Derbyshire photograph that the Beechey gravemarkers used serifs extensively. They may well have been useful in establishing a boundary from which a letter could be carved out — thus making them the deepest cuts of all into the wood.

The photograph below spotlights where line 9 (Braine’s Bible verse) should be. The word “will” is on the far right. Here a search for other readable words and letters – even with a flashlight at a shallow angle – was defeated by the irregular deterioration of the wood.

{ ▽ Line 9 spotlighted. }

However, across that line, there are clusters of very small horizontal cuts – not half the width of your fingernail – with nothing apparent connecting them.

{ Three small horizontal cuts. }

For some reason, they all exhibit a slight orange hue. That bit of color was what first caused us to notice them.

Individually, they appear unconnected and random. And so we initially ignored them, amidst the many other various marks on the aging gravemarker.

But when these particular little orange cuts are separated out as their own group, their distribution does not seem random.

{ ▽ Line 9 horizontal cuts circled. }

From that same highlighted section above, consider the following discrete area.

{ ▽ Section of line 9. }

Here the irregular contours of the wood defeat the ability to recognize where the primary strokes of the letters once were, even with the use of a flashlight.

But with an eye towards focusing on potential serifs, this picture changes.

{ ▽ Potential serifs circled. }

When considered as serifs, one can convincingly draw in the missing letters. This is now a game of “connect the dots.” Most readers will have already guessed the solution to this word: this is “whom” from “Choose you this day whom ye will serve.” Knowing this, some diagonal cuts from the letter “w” are still discernible.

Meanwhile the letter “o” is today invisible, as that letter would naturally lack serif marks.

{ ▽ “whom” serifs. }

Thus a lost word from Braine’s Bible verse, unrecognized by Hansen in 2016 and ourselves in early 2023 — even with the Derbyshire photograph in hand — can be recovered by finding and connecting the remains of these tiny cuts.

Having identified “whom” and the word “will” earlier above, we can now look between these words to identify one of the two contested pronouns from Braine’s Bible verse.

{ ▽ Identifying the 2nd pronoun. }

This is distinctly “ye”, not “you” — just as the Derbyshire photograph had hazily suggested. Indeed, now that we know where to look, it is possible to still faintly discern the ridges of the entire letter “e”.

Thus the last part of the Bible verse was written, not “whom you will serve,” but “...whom ye will serve.” Sutherland had been right.

With this question answered, we can continue moving left through the serifs, to try to reach the 1st pronoun. Immediately preceding “whom ye” should be “this day”.

{ ▽ “this day”. }

The position of “day” is clear, and the position of the letters “hi” in “this”. But here we reach the most bizarre observation contained in this study. Earlier in this section, when examining the Derbyshire photograph, we had commented that: “...the position for “this” rather looks like a word beginning with a capital letter “C”.” Such a letter was so out of place, we dropped the photograph and turned to the surviving gravemarker to try to explain it. Now the serif marks have carried us to that same position on the gravemarker. And there, in the wood itself, we can observe... a prominent knot, also resembling a capital letter “C” (see above for clarity, see below for position and comparison).

{ The knot and the apparent letter “C”. }

Perhaps an illiterate or semiliterate painter, told to fill in the carved letters with white paint, mistook this knot for a carved letter. Such an idea could suggest that the photograph is showing us the post-1853 repainted graves, as less care attends maintenance than a debut.

This knot can also be read as a solution to Powell’s question of authenticity for Braine’s gravemarker. Without the Derbyshire photograph, there would be no reason to take notice of this knot in the wood — and, without the surviving gravemarker, there would be no explanation for the strange apparent letter “C” in the Derbyshire photograph. These two together seem to be the matching halves of a locket, their relationship suggesting that the block of wood in Nunavut’s storage is indeed the one seen in Derbyshire’s historical photograph.

Continuing further along the line, just ahead of “this day” we should find the answer to the question of the first pronoun: either “Choose ye” or “Choose you”.

However, here the trail of serifs begins to vanish. All that remain are two.

{ ▽ Two serifs remaining. }

These two serif marks must belong to the letter “y” from the pronoun, as the next word “Choose” would have not had serif marks at this (mean line) height. The word “Choose” seems to have been entirely obliterated.

And if that pair of serif marks must be a letter “y”, then the missing pronoun must have been “you”, not “ye”. The serif marks are simply too far away from the next word in the inscription (“this”). The word “ye”, consisting of just two letters, is not enough to have filled the space between.

It is also possible that part of the carving of a letter “u” has survived over a nearby knot (see arrow below).

{ ▽ Potential carving marked by arrow. }

This potential letter “u” lines up well with the Derbyshire photograph. In the image below, the arrow marking the potential letter “u” is in precisely the same position over the wood as in the image above. From that position, it does indeed mark where the first pronoun had ended in Derbyshire’s photograph.

{ Transparent Derbyshire photograph over the surviving gravemarker. }

Additionally corroborating this reading, the tail of the letter “y” may be just discernible at the very edge of Derbyshire’s photograph. [For those looking closely at this, note that there is a distinctly darker trough along the edge where letters across Braine’s inscription fade out before the photograph ends. It has been left opaque in the image above in order for its remains of letters to still be discernible, such as that which appears to be the tail of the pronoun’s letter “y”. This same “fading letters” effect occurs at lines 5 and 7.]

While these remains are scant, we believe in particular that the distance of the twin serifs from the next word are sufficient to conclude that the first pronoun must have been “you”, not “ye”. It is also, incidentally, the correct pronoun set from the verse in the King James Bible: “Choose YOU this day whom YE will serve.”

To admit this is to suggest that Sutherland – who otherwise had not placed a single letter wrong until now – has made his first mistake. This would, and did, give us pause. However, in the final two sections below, each will suggest further deviations by Sutherland on Braine’s gravemarker.

BRAINE 2 of 3: The date of death.

Armed with this strategy of looking for the surviving serifs, we can attempt to answer the question of Braine’s death date: Did Braine die on April “3rd”, or April “3d”?