December 3, 2020.

Summary: An article arguing that a rake that disappeared in the Victorian era was the first Franklin relic ever found, that it's been hiding unidentified in two relic sketches, and that this rake most likely belonged to naturalist Harry Goodsir.

|

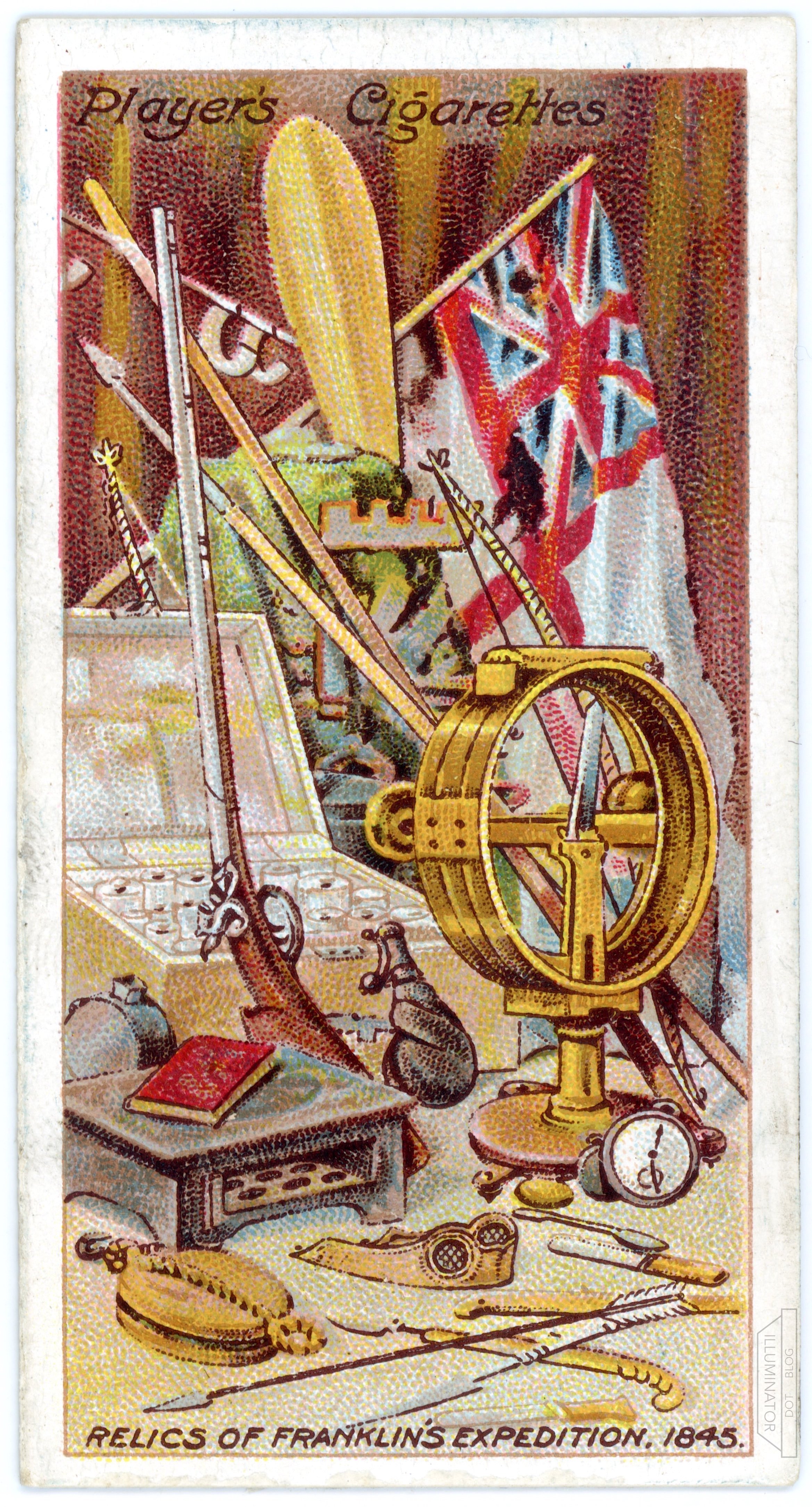

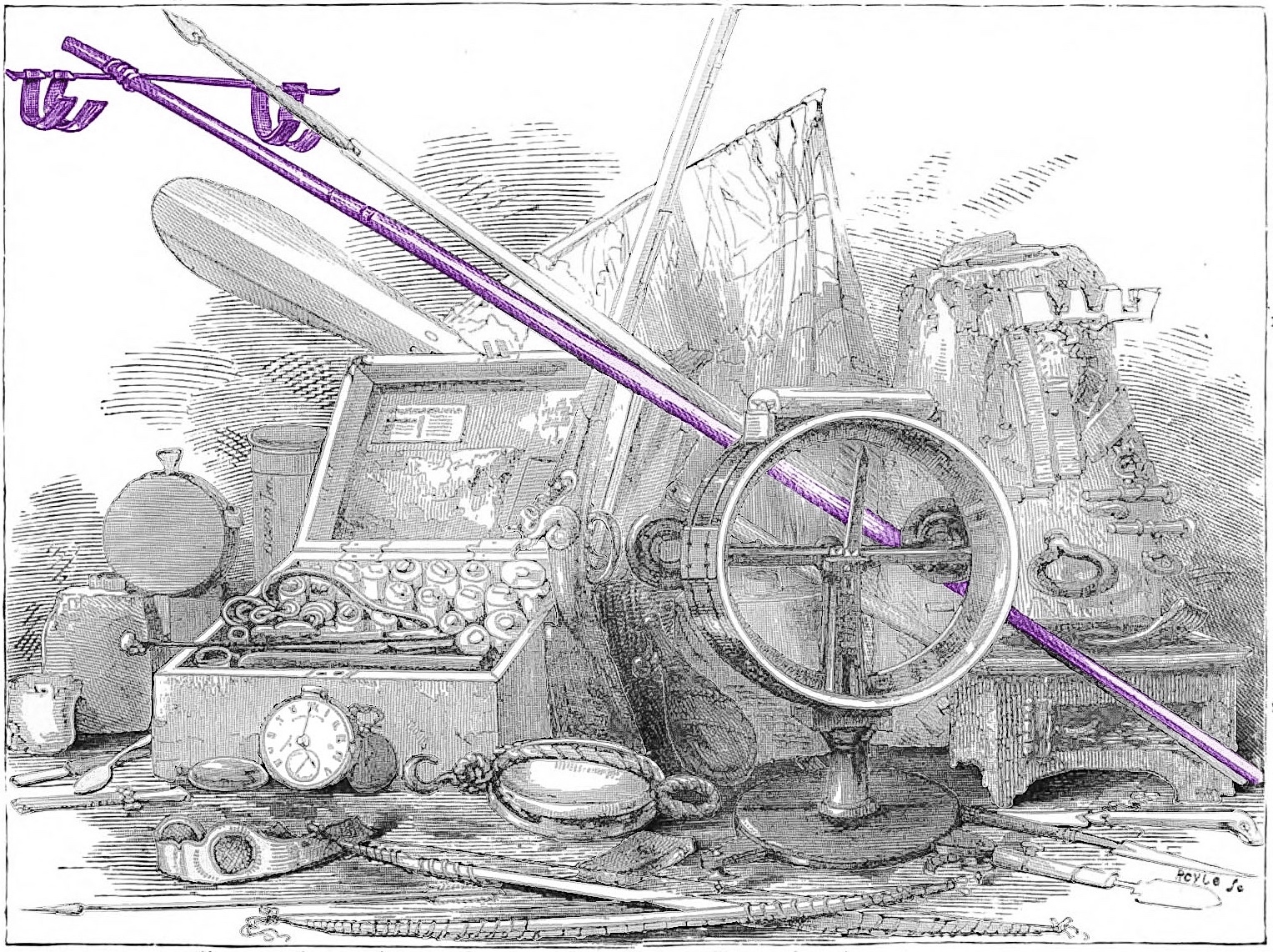

| Franklin relics, 1915 vs. 1878. |

How many relics appear twice, once in each of the sketches?

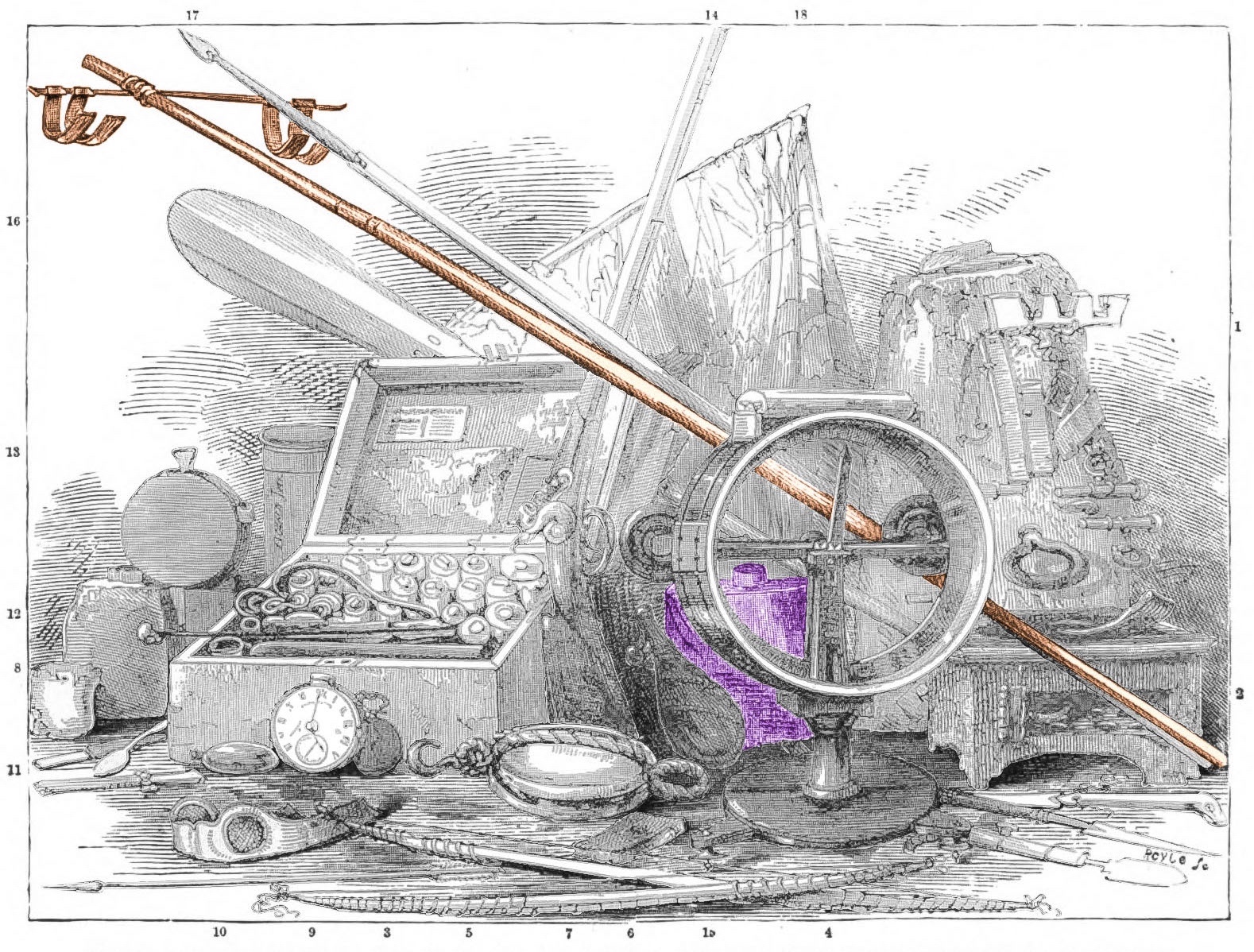

Two Franklin relic sketches drawn a generation apart – 1878 (black and white) and 1915 (color). One appeared in books, the other came with a pack of cigarettes.

And yet, when you compare them relic-for-relic, a remarkable number of similarities start to appear. I believe these are, in fact, the same sketch. Despite a few position changes, everything is drawn in a similar (even copycat) manner. The Players Cigarettes artist in 1915 must have used the older sketch as a template, squeezing the relics still life into the upright 'portrait' frame. [One clue: The expedition flag had been too fragile to hang from a staff even 20 years earlier, yet both sketches depict it in this same idealized manner.]

By my count there are 31 total relics here, and 29 of those 31 are in both sketches. [One of the sketches has 2 relics that the other does not; one is very debatable. More on this further down.]

* * *

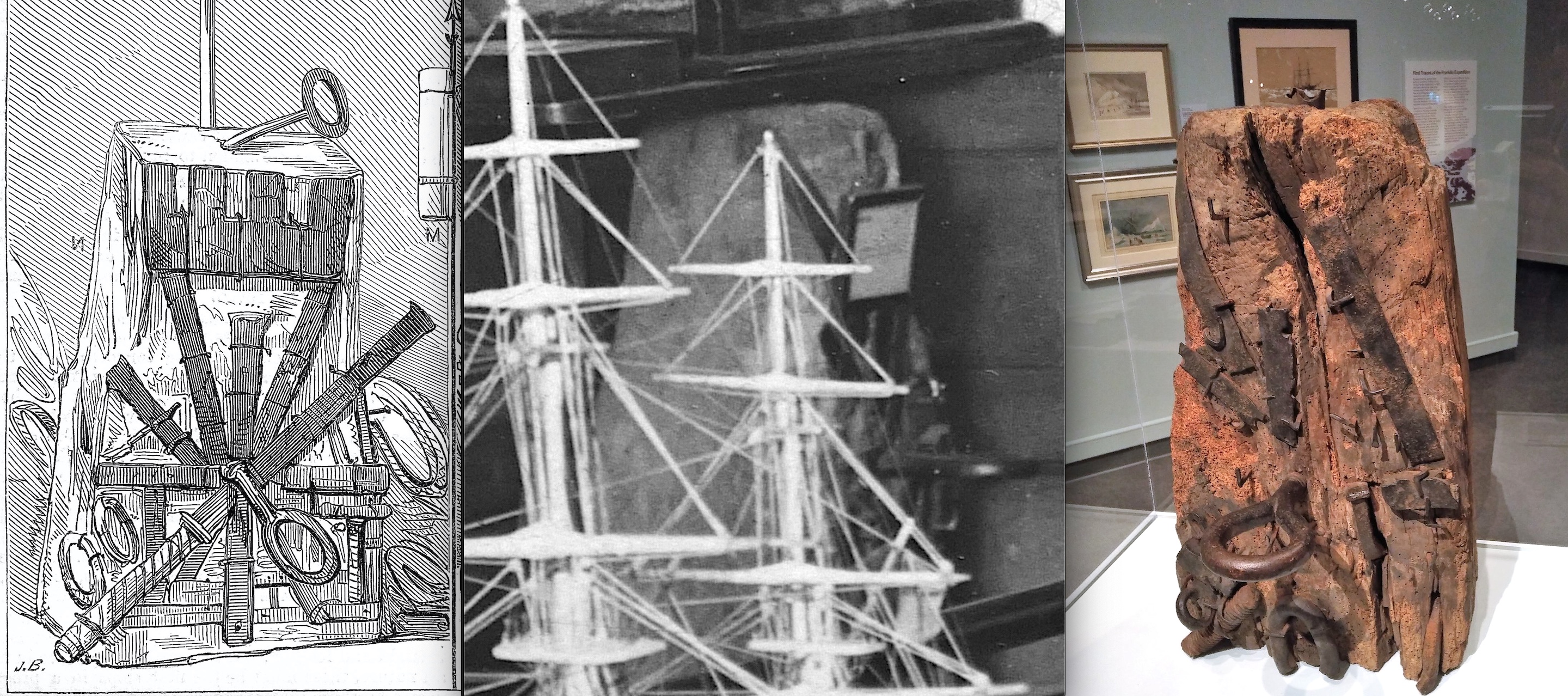

|

| The 1878 sketch, one relic highlighted. |

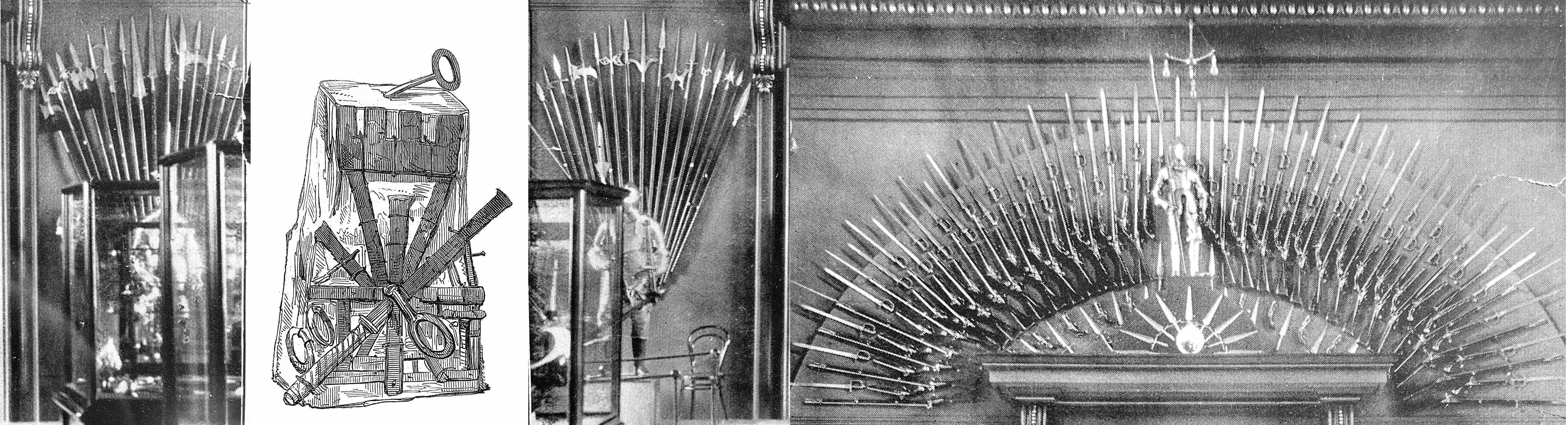

That same sketch produced a surprise in 2015, when illustrator Kristina Gehrmann questioned what the bizarre relic on the far right could be. [A Victorian dalek or R2-D2, as Kat Stoetzel put it.] Dozens began jackhammering at the question in a thread on RtFE. This went on for nearly a month, until Regina Koellner solved the puzzle: it was the Beechey Island Anvil, in the RUSI Museum, with the iron ornaments (its disguise).

In the years since, much of the story has been filled in. Russell Potter found a sketch showing the original configuration of those iron ornaments. This website found the earliest known photograph of the Anvil, from 1927. Most remarkably, the Anvil itself has survived and been found. Regina Koellner’s sketch identification ended up in Garth Walpole’s book of relics, and that book would be consulted in 2018 when the Anvil was located in Canada. It had been hidden for half a century in the Glenbow Museum’s storage, in Calgary. By the end of that year, the Anvil would be the star of a Glenbow exhibition. [For further Anvil details, see Appendix 5.]

In the years since, much of the story has been filled in. Russell Potter found a sketch showing the original configuration of those iron ornaments. This website found the earliest known photograph of the Anvil, from 1927. Most remarkably, the Anvil itself has survived and been found. Regina Koellner’s sketch identification ended up in Garth Walpole’s book of relics, and that book would be consulted in 2018 when the Anvil was located in Canada. It had been hidden for half a century in the Glenbow Museum’s storage, in Calgary. By the end of that year, the Anvil would be the star of a Glenbow exhibition. [For further Anvil details, see Appendix 5.]

|

| The Beechey Island Anvil: 1858, 1927, 2018 |

The whole story is a favorite of mine, particularly the crowdsourced analysis in the original 200-comment thread – a model for what a possessed history club can accomplish as a mob.

In that same sketch, I have identified another lost relic. Unlike the Anvil, it will almost certainly never be rediscovered. It is the only depiction we have of a once famous Franklin relic – one that would point the way to Beechey Island.

* * *

The first step is to use this particular printing of the sketch, revealing the relics' location as the lost 'RUSI Museum' in London. Beneath that caption, this version has a numbered description of eighteen relics in the sketch, from Anvil (1st) to Ensign (18th).

Then we count through the numbers, identifying the relics:

As we cross off identifications, something unusual happens: the list runs out, while two relics remain unnamed.

One is the pocket flask recovered by McClintock – the curve along the top edge gives it away. It was first identified as Greenwich's Flask AAA2168 by Don Noble in 2015, in the original thread debating the Anvil relic.

With the flask identified, just one relic remains.

What is this? What was it for? Why didn’t the sketch have a name for it?

* * *

|

| The RUSI Library, upper gallery, winter 2019. |

The 1878 relic sketch was drawn at London's lost RUSI Museum. While their collection is gone, the RUSI institution still exists, at the Museum's final location on Whitehall, London. Their library holds the minutes from over a century of RUSI meetings, and these allow one to trace the Franklin relics as they entered the museum.

Here is the entry for the first Franklin relic received, in late 1851:

|

| 'An Implement resembling a Rake' |

There are none before this. Before Rae, and long before McClintock, it was this Capt. E. Ommanney who discovered the first traces of Franklin. We think of Beechey Island as the place where relics were first found, but it was this discovery of relics at Cape Riley – just across the bay – that led searchers to discover the secret at Beechey Island.

Later, Capt. Ommanney would donate more of the Franklin relics he'd found to the RUSI Museum. But after returning home in late 1851, he began by donating just this one. This notice then is the birth certificate of all Franklin museum collections today. What would eventually become a multi-national collection, touring the modern world as Death In The Ice, started at one London museum with one relic on display: “An Implement resembling a Rake.”

And Ommanney's donation note gives it quite a designation: “the first trace found.” Not 'among' the first traces – the first. The first Franklin relic.

This is tragic; no Franklin 'rake' is listed in any museum collection today. It's lost. We have neither photo nor sketch of this lost rake relic.

|

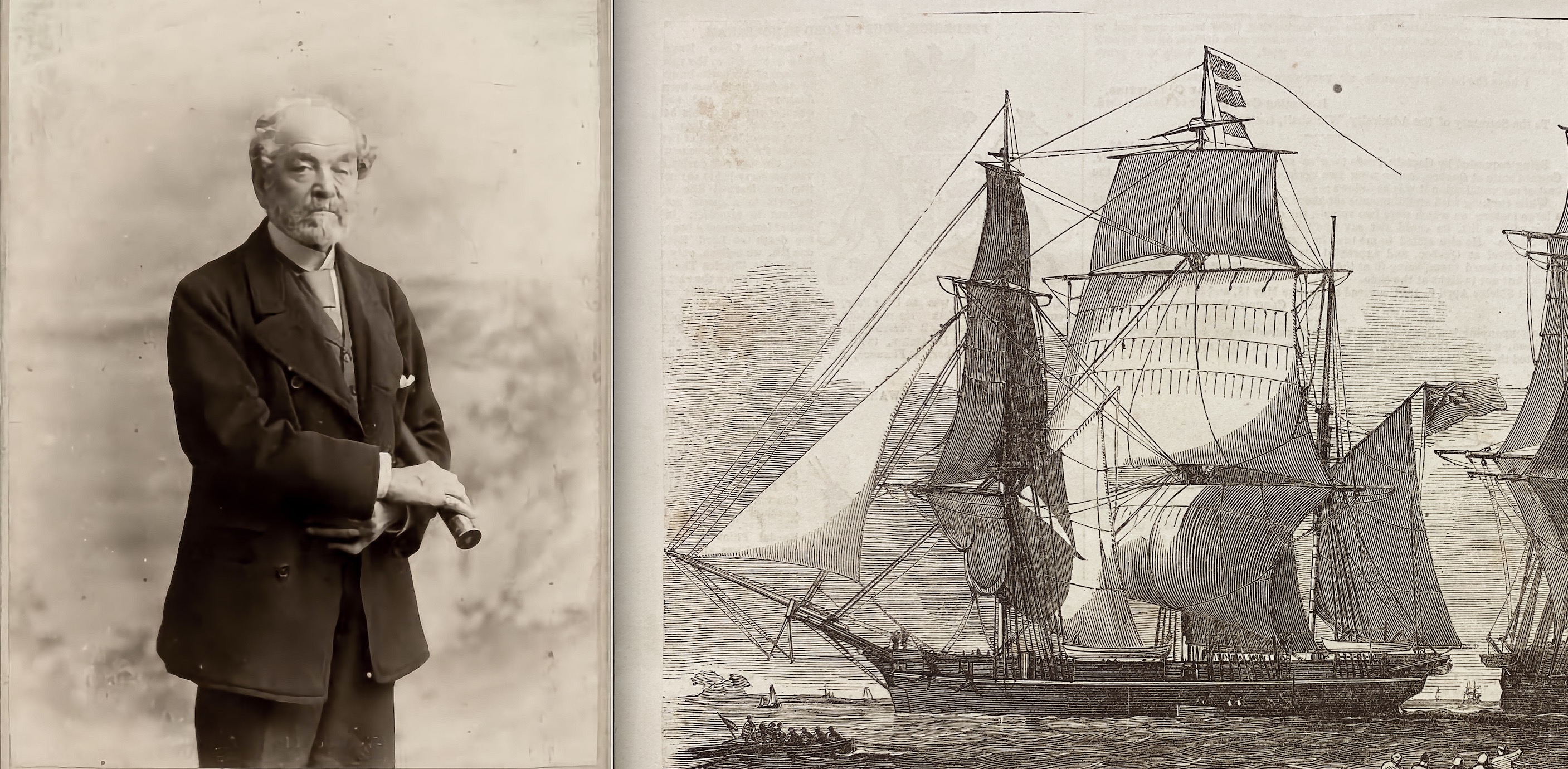

| Capt. Erasmus Ommanney and his search ship HMS Assistance. |

Nor is the RUSI's acquisition notice the only attestation of the Rake as First Relic. Returning from his search for Franklin, Ommanney's ship HMS Assistance arrived in London on October 6th, 1851. Of all the relics he brought back, the newspaper report on his arrival mentioned only one:

Captain Ommanney has brought home the first relic that was found by him of the traces of Sir John Franklin’s party at Cape Riley. It appears in the form of a rake, such as are used by persons employed in collecting seaweed. (Woolwich, 6 Oct 1851)The italics are mine. Here a different source has spoken to Capt. Ommanney, and – like the RUSI Museum – they have come away from Ommanney with the same story: that the Rake was the first Franklin relic found.

The newspaper also gives an assessment (presumably Ommanney’s) of what the Rake was for: “such as are used by persons employed in collecting seaweed.” Who collects seaweed? The same person who would catch phenomena in a bucket: an expedition naturalist.

|

| The (current) Royal Geographical Society headquarters in London. |

That opinion would be echoed six weeks later at the Royal Geographical Society. Capt. Ommanney spoke there on November 24th about his search. He seems to have only brought one relic to his talk – the Rake, stood in the corner. Two newspaper accounts reported it as a naturalist's tool:

...the spar exhibited in the corner ... was afterwards explained to be a rake used by the naturalists for bringing up weeds or other substances from the sea. (The Morning Chronicle, Nov 25 1851)The long naturalist’s rake, which was among the articles found, was here exhibited to the meeting, and was much and curiously examined. (The Daily News, Nov 25 1851)

“The long naturalist’s rake.”

* * *

Could the unidentified relic in the sketch be that 'long naturalist's rake' then, the rake found at Cape Riley? No one has seen the Cape Riley Rake since the Victorian era. There is neither photo nor sketch to compare to.

We do, however, have written descriptions of the Rake.

a ash pole with a cross head attached to it there from some hooks of bent iron. (Ommanney's journal, 23 Aug 1850)a long staff, with a cross piece attached to it. On the cross piece were lashed four bits of iron hoop, bent like hooks. (Clements Markham, 1853, Franklin's Footsteps)An Implement like a Rake, having a very long handle, and a rude cross-piece of hoop-iron, with hooks of the same material, fastened at the end. (Parker Snow 1858)The handle is about twelve feet long, and the gathering part about two feet six inches long, on which six teeth have been fixed about five inches each in length, formed of narrow hoop iron curved inwards. (Woolwich, 6 Oct 1851)

Two identifying details stand out from these descriptions: teeth and dimensions.

Markham wrote that the Rake had four teeth; the reporter in Woolwich said six. Our mystery relic in the sketch has four teeth. One can argue that Markham would be the more reliable account. Young Clements Markham was actually serving on Ommanney's ship on this expedition; he would have been looking at the Rake all winter on board HMS Assistance. But it's notable that the Woolwich report is only off by two – one tooth on each side; it’s not off by, say, 5 or 10 teeth. The Woolwich writer evidently saw the rake, and is within a reasonable range of error.

The other identifying detail is the Woolwich report's dimensions: they write that the Cape Riley Rake was “about twelve feet long” with a crosspiece “about two feet six inches long.” If you set the sketched relic’s length for 12 feet, you'll get a cross piece of 2 ft 10 in wide. This also is within a reasonable range of error.

To put this unusual ratio in everyday terms: the crosspiece of the push broom in your garage is probably two to three feet wide, just like the Cape Riley Rake's. That means your garage broom is now 12 feet high, about double your height standing next to you.

Given that unusual ratio, the physical descriptions, the four teeth counted by Markham, and the sketch's stated location at the RUSI Museum, we can be confident that this unnamed mystery relic is indeed the Cape Riley Rake. No other Franklin rake was ever recovered. There was one Rake, it was donated to the RUSI Museum, and here is a sketch of a rake identified with Franklin at that same museum. The shock is that it hasn't been identified before – not even in the sketch's list of relics.

* * *

Despite this identification, and despite vanishing a century ago, the most intriguing mystery regarding the Rake relic is still this: that it puzzled the searchers who found it. "Many conjectures were formed at the time as to what this had been used for," recalled Robert Goodsir, younger brother of the Erebus' Harry Goodsir and a member of the Arctic search squadron when the Rake was discovered.

Markham would write, "For what this [rake] could have been used no one has been able to conjecture." Capt. Ommanney at first wrote that it was for fishing, later said it was for collecting seaweed. Capt. Belcher argued that it was for finding edible algae, then said it was for objects of natural history. The RUSI acquisition notice wouldn't even outright label it a rake; it was written as, "Implement resembling a Rake."

What is missing here is more notable than what is said. No one is coming forward to say, "I recognize this object, we used such things on Ross/Parry's voyages, for X purpose." The consensus ended at a naturalist's tool, but – between all the Arctic veterans and all their firsthand Victorian sailing knowledge – no one recognized this device.

Therefore someone on the Franklin Expedition was doing something new. If a naturalist, then it would be someone eager to make new discoveries and determined enough to be trying new methods. It's hard not to suspect the Erebus' Assistant-Surgeon Harry Goodsir. Though others were involved in the natural history work, Goodsir held a position of prominence; he wrote home that his shipmates were “all very active in assisting me” obtain specimens (emphasis mine), including his own Commander Fitzjames. Harry had authored numerous papers on natural history. He only went as Assistant-Surgeon as there wasn't a dedicated position as Naturalist. Commander Fitzjames’ writings are littered with vignettes of Harry Goodsir catching phenomena in a bucket, being in eccstacies about hauling up a bag full of blubber, etc. Indeed, Harry had shown a zeal for this work since childhood. If anyone on the Franklin Expedition was constructing a new, unfamiliar device for natural history work, Harry Goodsir tops the list of suspects.

It's been speculated that Franklin's men left their winter camp in a great hurry, an early breakup of the ice being more important than leaving a cairn note. On that day – like a sailor grabbing for a ring he'd forgotten on shore – the owner of the Rake may have turned to look back as Erebus and Terror sailed, realizing he'd left something at Cape Riley. The long and straight Rake would lay unseen on a rocky beach for four winters, until one day – an ash pole in a land without trees – it caught the eye of a search party landing under Capt. Ommanney. The discovery of the Rake and other scattered relics at Cape Riley would focus the 1850 search squadron extremely close to an island named Beechey. On a morning four days later, another search party would crest a rise coming from the west side of that island. Someone would yell and they would begin to run "at headlong speed" down the beach, Harry Goodsir’s younger brother Robert in the lead – throwing his Dollond telescope and then peacoat off his shoulders, seeing relics we would recognize today passing under his feet, crossing the inner shore of Beechey Island toward the discovery of the three graves.

Perhaps Parks Canada will recover journals that explain what the Cape Riley Rake had been made for, and who had used it. Perhaps their dive team will come across another such rake, 12 feet long with 4 iron hoop teeth, still aboard one of the ships.

– L.Z. December 3, 2020.

Robert Goodsir’s unique eyewitness account of the discovery of the Beechey graves was located in 2018 by Alison Freebairn, in a pseudonymous 1880 Australian newspaper article (link to transcript at Finger-Post.blog).

|

| The sighting of the graves. (Illustrated London News, Nov 29 1851, p. 637) |

* * *

Appendix 1: What happened to the Rake?

The Cape Riley Rake's last sighting appears to have been at the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition in Chelsea, London. That was likely the first time it had left the RUSI Museum since arriving in 1851. Not many years later, the Rake is missing from the RUSI Museum's own catalogue (1908). It does not appear in Greenwich's Royal Naval Museum catalogue in 1913, nor in the Arctic liquidation records when the RUSI Museum closes in the 1960s (link to Illuminator article).

Therefore when the Cape Riley Rake appeared on packs of Player's Cigarettes in 1915, it was already a missing relic.

Perhaps a workman cleaning up the 1891 exhibition grabbed it for some task; a 12 foot hook can come in handy. That height is the most damning piece of evidence in hoping that it might be found: it's not easy to hide a 12 foot rake, even in a museum archive. If Greenwich had it, they'd probably already know about it. Therefore the 1878 (and 1915) sketch is likely to be our only view of the Cape Riley Rake (it's not visible in the photographs of the Franklin Gallery from the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition).

[Note: I stated that the 1908 RUSI Museum catalogue doesn't list the Rake. Yet it does have a catalogue entry for a group of Ommanney-Franklin relics, which are not enumerated. We can be certain, however, that the Rake is not in that group (article forthcoming – add link here, Logan).]

Appendix 2: Harry Goodsir’s Rake?

Could this really be Harry Goodsir’s naturalist rake, something he used while wintering at Beechey Island? It's worth breaking this argument into two parts.

Connecting a "naturalist's rake" to Harry Goodsir is my own call; no one said it at the time. Similar to my argument connecting the McClintock Toy Sledge to Erebus’ timbers not Terror's, it’s likely but unverifiable. Certainly other people on the expedition were involved in collecting specimens; there’s evidence of this in the letters sent home from Disko Bay. Harry Goodsir is merely the most likely person to be involved, based on circumstantial reasons like his particular zeal, his preeminence in the specimen collecting on Erebus, the fact that the rake struck the Victorians as an unknown/new method, etc. A stove pot most likely belongs to the cook.

But the other half of this argument – that this bizarre rake was used for collecting natural history specimens – is not my argument. It’s theirs, the Victorian searchers. This is a bigger leap than proposing that a naturalist's tool would be associated with the most ardent naturalist. I would have guessed that there might be 1,000 uses for a rake on an Arctic expedition; if we put this question to people today, they’d probably all say the rake was for fishing up something sunk in the water. And yet we have two Royal Navy men – captains no less, of the Victorian era – going public saying they don't recognize this device. Ommanney had been in the navy since age 12, Belcher since he was 13. They had lived their entire adult lives around ships, harbors, and shores. They would have seen or used every imaginable tool in their trade – certainly anything you might fish something out of the water with. Yet Captain Ommanney stands up in front of the Royal Geographical Society and can't identify this thing – says that it must have been a naturalist's tool. Captain Belcher (in his 1855 book) was still debating with the rake's purpose even half a decade after its discovery.

Nor can I find anyone contradicting the "naturalist's tool" identification. If the Rake had resembled a recognizable tool to pull, say, a rope out of the water, there would have been a long queue to mock two Royal Navy ship captains for missing that fact. People as disputatious as Old John Ross and Richard King are out there, and they’re apparently silent on this topic. Clements Markham and Robert Goodsir both report that the rake's purpose was a much-debated topic (and Belcher's initial comment alludes to this: "Again, for what use was that rake?"). Whatever we might conjecture about this object today, we have to start by accepting that the Victorian Royal Navy emphatically didn’t recognize it, didn't think it belonged to their trade. And they generally concluded that it must be the tool of a naturalist. And notably, so did Harry’s brother Robert Goodsir, from a family where dredging things up from the water had been going on since childhood. He wrote that the rake looked to him like, "something between a long grappling iron and a naturalist's dredge."

Appendix 3: First Relic – Additional Arguments.

Implement found on Cape Riley, (The first trace of the missing Expedition, by Capt. Ommanney.)– from the ‘Kelly Catalogue’ of the 1859 McClintock relics exhibition.

"The first trace." This is a 3rd source listing the Rake as the first Franklin relic. It's from a catalogue written years later when the McClintock relics arrived at the RUSI Museum (for more detail, see the Appendix at the end of this linked list).

On one hand, we can reasonably dismiss this source as just an echo of the Rake's original RUSI acquisition notice from 1851. The catalogue author is noting down the museum's info card, and that info card would logically have been written from the museum's acquisition notes (the word "implement" has survived, as it did in Snow's 1858 list). Therefore this "3rd source" is likely a mere repetition of the 2nd source.

On the other hand, the year is now 1859. That means that the Rake has been listed as "the first trace" at a public museum for 8 years. And for 8 years, evidently no one has contradicted this – not the other sailors on the Assistance, nor the Admiralty, nor the other searchers. This fact alone is a strong argument for concluding that the Cape Riley Rake was indeed the first Franklin relic. That generation of Victorian searchers evidently accepted it as such. [Which makes it all the more disconcerting that it was later lost.]

What are the arguments against the Rake as First Relic?

I believe the other contender is Bottle AAA2031. In 1908, the RUSI Museum Catalogue had listed it as "the first trace." However prior to that, in 1891 (RNE Souvenir illustration) and 1858 (Parker Snow), it was merely listed as being in "the first traces" group. [If I'm missing an earlier attestation of the Bottle as the first relic, please send it to me.] So the Bottle has a claim, but it seems a weaker (and much later) claim than the Rake's.

[As an aside– That Bottle AAA2031 is often listed as a Beechey Island relic – including by Greenwich, from as far back as Ann Savours 1999 relic list up to the museum website (link) as of this writing. This should be changed to Cape Riley. Ommanney's journal (23 Aug 1850) reports "bottles" found at Cape Riley, but no bottles found at Beechey Island. Referring to "Beechey Island" as a catch-all geographical term that includes Cape Riley was as much of a habit for Victorians as it is for us today. Indeed the Rake is also sometimes referred to as a Beechey Island relic. These statements are true in a messy general sense, but in an exact sense, Ommanney's journal splits the hairs of where each was found. Further, being considered part of the "first traces" relic group implies Cape Riley in and of itself.

As a further aside– In his book, Elisha Kent Kane even argues for dropping the Island and just saying "Beechey," a habit indulged in to this day. "I drop the Island." – Kane.]

But in making an argument against the Rake as First Relic, the issue isn't the Bottle, or any other relic. The issue is that Capt. Ommanney was evidently a man of few words. Nowhere in his ship's journal does he say which relic was spotted first, or narrate that first moment of discovery. Other searchers (Snow, Penny, the Americans) were frustrated with – even suspicious of – the thin explanations in Ommanney's cairn note, which doesn't enumerate a single relic. Ommanney never clarified the narrative in his expedition book, because he never wrote an expedition book.

Ommanney, in his defense, was looking for men, not relics. When Ommanney shot off west to Cape Hotham, it looks like a blunder to history, missing the discovery of the full Beechey camp and its three graves. But record cairns weren't built hidden behind islands. Immediately after Cape Riley, Ommanney took apart a cairn on top of Beechey Island that he knew Franklin's men had built; he had every reason to believe the next point of land west, Cape Hotham, could have another cairn – and this time with written records inside. Ommanney's last concern in late August 1850 was journaling about how exactly he had found a rake on a beach, or which exactly of the traces at Cape Riley was spotted first. He couldn't have known that his first discoveries would be his last discoveries, some of the only clues we have over a century and a half later.

It's possible that Ommanney feared his relic-less superior officer (Captain Austin on HMS Resolute) appropriating his relics as leader of the overall expedition. Or he may have feared others stealing his story, as did somewhat happen. [Capt. Forsyth of the Prince Albert – displaying exactly this kind of secrecy – concealed the story of Ommanney's first traces discovery from HMS North Star, then raced home and broke the news of Cape Riley back in Britain, a year before Ommanney himself would return. See Ross 2019.] Ommanney at Cape Riley wrote a cairn note detailing not a single relic he'd discovered. Then on September 10th, he wrote an official report (Blue Book 1852a) of his discoveries to his superior Capt. Austin, mentioning tins, stores, and clothing – and no rake. Yet when Ommanney reaches London next October, he's brandishing the Rake at a reporter as he docks at Woolwich, making it the star relic of his November presentation at the Royal Geographical Society, and then (before that year is up) graciously donating it and it alone – as the first Franklin relic found – to become the first Franklin relic entering a London museum.

We would probably know much more if Ommanney's first discoveries hadn't been outshone by Capt. Penny, whose men discovered the full winter camp and its graves. Or if Ommanney hadn't been beat to London by Penny, his relics appearing as handsome newspaper sketches 48 hours before Ommanney could dock. Or, indeed, if Forsyth hadn't turned tail for home in 1850, making Ommanney's Cape Riley discovery into very old news by the time the Rake arrived in London. Or if Ommanney had been a better salesman of his story – or had written a book. For whatever motive, Ommanney doesn't seem to have trumpeted the Rake as the first relic until the moment he reached London. By that point, the public story had moved on. No newspaper seems to have even sketched what Capt. Ommanney was identifying as the first Franklin relic ever found. After the Anvil, the iconic Fingerpost, and the haunting Beechey graves, a rake isn't a headliner. Everybody owns a rake.

And there's a simple enough explanation why the Rake didn't seem important to Ommanney until it crossed the Atlantic: the search had failed. No men and no records were coming home. The Cape Riley Rake was no longer a mere stepping stone to greater things; rather, it was the single most important discovery Ommanney had made, the key that had unlocked Beechey. The Rake became First Relic, primus inter pares, in the mystery that had just thrown back an armada of search ships.

[As a piece of circumstantial evidence– In the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition catalogue, no single relic is identified as 'the first relic.' There's a label for some relics as "the first traces," but it is inaccurate (e.g., the Anvil is in there). However – in a catalogue organized fairly chronologically, from Ommanney to Schwatka – the very first relic of the first section is indeed the Rake. It's listed alone in its own paragraph, followed by its sister relics from 1850-51 all grouped into the 2nd paragraph.]

Appendix 4: The "Cape Spencer rake" – a 2nd Rake?

Was a 2nd rake discovered?

There was a search party that walked the shore near Cape Spencer, a few days after the Cape Riley Rake was picked up. One man in that party said he’d found a rake that day. Another man said the Cape Spencer search party told him they'd found a rake.

These accounts seem to confirm each other. I’m going to argue that both of these men were mistaken. They happen to be two of the most famous men on the 1850-51 search: Robert Anstruther Goodsir and Elisha Kent Kane.

Robert Goodsir (brother of Harry) had wrote that he, “picked up a nondescript sort of apparatus made of hoop iron, something between a long grappling iron and a naturalist's dredge.” This occurred on “the day previous to” the discovery of the graves – which is the day Goodsir was on the Cape Spencer search party.

Of that Cape Spencer search party, Elisha Kent Kane would write that, “They told us, too, that among the articles found by Captain Penny's men was a dredge, rudely fashioned of iron hoops beat round, with spikes inserted in them, and arranged for a long handle, as if to fish up missing articles.”

Both of these relic descriptions resemble the Cape Riley Rake: long handle, hoop iron, ambiguity about what it’s for.

For myself, I would find this highly interesting if another ‘Implement Resembling A Rake’ had been deployed in the opposite direction from Beechey as the Cape Riley Rake. I would use that to argue that this implies some sort of systematic expedition use, eliminating the chance that the Cape Riley Rake was constructed merely to solve one temporary or unusual problem encountered at Cape Riley.

But while Goodsir and Kane’s accounts seem to confirm each other, they break down when compared to the rest of the documentation. I believe they are each distorted recollections of the Cape Riley Rake.

The most critical detail about Robert Goodsir’s “2nd Rake” account is that he didn’t write it until 1880 – thirty years after the event. [What, dear reader, were you doing in 1990?] Therefore his memory will naturally have distortions. Goodsir doesn’t even recall finding his rake at Cape Spencer: he believes that he was at Cape Hotham that day. His recollection of that day before the discovery of the graves involves sailing across Wellington Channel to Assistance Harbour, then searching the coast on foot back to Cape Hotham, yet somehow arriving back at his ship – which he says sailed to Beechey Island whilst he searched. This would necessitate that Goodsir hiked north for an extremely long and dangerous ice crossing – or that he took the direct route walking on water – because separating Cape Hotham and Beechey Island is 30 miles of Wellington Channel.

Goodsir is combining several experiences into one single day, and muddling the geography. Still, it is without question that the elements of Goodsir’s 1880 account are true: the day before the discovery of the graves, Goodsir was indeed searching land near a cape, a few relics were found, and he slept the night near Beechey Island. The cape searched was Cape Spencer, not Cape Hotham.

But was Robert Goodsir right that he had found a rake that day – the day before the graves were found, the day he followed his superior officer Captain Penny on a search of Cape Spencer?

Elisha Kent Kane states that someone on that Cape Spencer search party told him that they had found a rake: “They told us, too, that among the articles found by Captain Penny's men was a dredge, rudely fashioned of iron hoops beat round, with spikes inserted in them, and arranged for a long handle.” It's clear Kane wasn’t there himself, nor did he lay eyes on the relic; he’s recording both the story and the relic's description secondhand.

Very notably: Kane’s book never mentions a rake from Cape Riley. This “2nd rake” from Cape Spencer is the only rake in Kane’s book.

There’s a list of relics recovered by Captain Penny's ships in the Admiralty papers (Blue Book 1852c), including a section labelled Cape Spencer. No rake is listed there.

Regarding his rake discovery, Goodsir in 1880 would write that, “Many conjectures were formed at the time as to what this [rake] had been used for.” If true, then it’s unthinkable that Captain Penny left such a debated relic on the ground in the Arctic, considering what trifles of relics he did return with (coal bags, a bread bag, pieces of wood, etc).

And if true, why didn’t anyone else mention this ‘much-conjectured’ rake besides Kane the American? And Goodsir – but only after 30 years had passed?

Indeed, Goodsir would give an account of what was found at Cape Spencer to the Admiralty after the expedition was over (Blue Book 1852c). In it, Goodsir never mentions a rake. Sutherland (a surgeon under Penny) in his book also gave an account of the Cape Spencer discoveries – which he thanks Goodsir for helping him with – and yet this also never mentions a rake.

How do we resolve all these contradictions?

The following paragraph outlines what I think happened:

On August 25th 1850, the day before the search party at Cape Spencer, we know that Captain Penny had gone aboard HMS Assistance in Wellington Channel. Here Penny saw Ommanney’s Cape Riley Rake with his own eyes. As Ommanney journaled, "[Penny] was quite overcome when I produced the relic which I had discovered at Cape Riley." The next day – when Penny led Goodsir and others to search Cape Spencer – the rake that Penny had seen would have been the main topic of discussion as they walked. In the days before the discovery of the graves, it was conjectured that the first traces were evidence not of a winter camp, but of a party fleeing their abandoned ships. Penny's men would have listened to him recount what Ommanney had said in person, asked questions clarifying the Cape Riley Rake's physical characteristics, and all engaged in debating the rake’s purpose and potential meaning. A few decades later, Goodsir's memory of contemplating that rake during the Cape Spencer walk was so strong, he actually believed he himself had picked it up that day. And when the Cape Spencer party returned and spoke to Elisha Kent Kane, they naturally spoke about the much-conjectured rake that Penny had been telling them about, and Kane mistook this as part of the Cape Spencer story.

Otherwise, it is unthinkable that Penny didn’t collect his own mysterious rake – the day after seeing Ommanney’s, and at a time when a shipwreck was still being debated. Unthinkable that Goodsir didn't mention a rake during his Admiralty testimony regarding Cape Spencer. Unthinkable that Kane the American would be told about the rake, but not Surgeon Peter Sutherland – one of Penny’s own men – who wrote about the Cape Spencer discoveries with Goodsir’s direct help.

Indeed, why would the Cape Spencer party tell Kane about a rake they had found, without mentioning that it very much resembled the one that their leader Capt. Penny had seen aboard HMS Assistance not 24 hours earlier? And why would Goodsir not compare his Cape Spencer rake to Ommanney's Cape Riley Rake, which he doubtlessly spoke with Capt. Penny about on that very same day?

Goodsir’s memory was clearly hazy with the distance of decades (as evidenced by his belief that these events occurred at Cape Hotham, all on one day, etc). Robert Goodsir can hardly be blamed for this: his journals had been seized and thrown down a bottomless pit by the Admiralty immediately after the expedition, as part of their feud with his superior officer Captain Penny.

But no such excuse of access to journals or decades of time apply to Elisha Kent Kane. Why did Kane never mention the Cape Riley Rake in his book? He certainly had all winter in the Arctic to have learned about it.

This misdemeanor by Kane may have a motive. As W. Gillies Ross lays out in Hunters on the Track (2019), Kane would dispute that Capt. Ommanney had alone discovered Cape Riley's traces; Kane argued (wrongly) that Ommanney co-discovered the Cape Riley traces with an American ship. This was actually Ommanney's 2nd stop at Cape Riley, and W. Gillies Ross argues that Kane certainly would have learned this fact over the winter. [Another British vs. Americans dispute would flare up over place-names in Wellington Channel.] When considering Kane's apparently invented allegations about who discovered the first traces at Cape Riley, I find it highly suspicious that in Kane's book, the 'first relic' of Ommanney's Cape Riley discovery gets taken away from him, teleported north of Beechey Island to be discovered by others. Kane’s “Cape Spencer Rake” story may have been a convenient way to mishear what he had been told, and thereby dispose of some inconvenient evidence that benefited Capt. Ommanney and scuttled Kane's own allegations.

The wrinkle is that, after enough time had passed, Robert Goodsir believed there had indeed been a rake found that day – that he Robert Goodsir had found it.

I have used the term "2nd rake" throughout this argument. No one did at the time. Even Kane and Goodsir agree with every other account on this point: there was only one rake. Their "Cape Spencer rake" recollections must be distortions of everyone else's Cape Riley Rake – an example from the kabloonas of what Louie Kamookak would have called a "mixed story" (Potter 2016).

[Robert Goodsir's account comes from a pseudonymous 1880 Australian newspaper article (link to transcript at Finger-Post.blog).]

[As an aside– Kane's rake account describes spikes on the rake: "iron hoops beat round, with spikes inserted in them." No other account describes these, and no spikes are evident on the rake in the 1878 sketch.]

Appendix 5: Notes on the Beechey Island Anvil.

There's a news article out there from as late as last year with the Glenbow Museum saying they'd eventually, "like to find out who brought [the Anvil] back." That is without question Captain Penny of the ship Lady Franklin, attested in a number of sources, the simplest of which to cite is the Illustrated London News Oct 4 1851. The date is as informative as the text: the ILN article featured a sketch of the Penny Anvil in print before much of the searching squadron had reached London (Ommanney, as mentioned earlier, arrived on Oct 6).

Who put the iron ornaments on the Anvil? Parker Snow, in his 1858 catalogue of the Franklin relics at the RUSI Museum, helpfully noted that, "The scraps of iron, eye-bolts, &c., have been fastened on to the block, since arrival at the Museum."

Historic photographs of the RUSI Museum show various examples of the 'upward fan of blades'-style of decoration, typical for military museums of that era. I believe that motif is what we are seeing in the Anvil's central pattern (5 Jan 2019 RtFE), which would corroborate Parker Snow's assertion.

How did the Anvil's ornaments get trashed? One might have suspected that this happened on the field trip to Chelsea for the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition; that was almost certainly the first time the Anvil left the RUSI Museum since arriving in 1852. However the '1878 sketch' shows us that over a decade before the RNE, the Anvil's ornaments were already well-scrambled. The 'eye-bolt' worn as a hat and the 'diagonal tool with handle' (likely to be a file, identified by Matthew Betts 31 Dec 2018 RtFE) are already missing by 1878. The 4-toothed crenellated piece worn as a visor, however, is still hanging on in 1878; by the 1927 photograph, it too is missing.

Some of the Anvil's ornaments might not be so much missing as misaligned. I drew this reconstruction (31 Dec 2018 RtFE) to show that – excepting the 'file' – most of the original fan-of-blades pattern may still be there, out of order (and in one case, hammered backwards).

Link to VotN coverage of the Anvil discovery.

Link to the CBC article on the Anvil's exhibition.

Appendix 6: Captain Belcher's Savage Adaptation of Rakes

Again, for what use was that rake? Not to take objects of natural history, but to detach the edible fuci, which my men and officers have repeatedly seen me seek, and eat with satisfaction. The inner low-water beach and rocks, immediately under the point at Cape Riley, furnish this fucus.… only in August, or later, when thaw had removed the ice, would we find men groping, with savage adaptation of rakes, in searching the bottom for objects of natural history.– Captain Belcher, The Last Of The Arctic Voyages, 1855.

This makes Belcher the only person saying he knows what the rake is for – on the grounds that he himself has used such a device, to consume seaweed, while his men and officers watched (presumably with mouths agape). Then a page later he reverses his argument; he says the rake was for natural history work, just a page after saying it wasn't. I find Belcher to be an unreliable narrator; I generally trust that he has the setting right (e.g., that the rake's purpose was debated just like this) but that his facts and conclusions may be distorted. These rake observations come in a section where he's arguing as late as 1855 against the idea that Erebus and Terror wintered in Erebus & Terror Bay. He says he collected a pile of relics to prove his argument, but then lost them.

Appendix 7: Bibliography

From Appendix 3 above: "Other searchers (Snow, Penny, the Americans) were frustrated with – even suspicious of – the thin explanations in Ommanney's cairn note..."

The frustration in Snow's book (1851) is couched in politeness: "most anxiously did I hope, at the time, we should communicate with the "Assistance," to get from her increased information. As we did not communicate with Captain Ommanney, the news here gleaned was all that we could gather: and, however vague and unsatisfactory such information of the missing ones might be, still it was something..." For the unvarnished reactions of Penny and the Americans, see Robert Randolph Carter’s Journal entry for August 27 1850 (“Penny swears to shoot him.”), also available where I first read it in W. Gillies Ross' Hunters on the Track. Also: Snow's book has Ommanney's cairn note transcribed.

Belcher, Edward. 1855. The Last of the Arctic Voyages. (See Appendix 6.)

Blue Book. 1852. 1852a/45227. Report of the Committee appointed by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty...

(p. xxxiii) fragments of naval stores, ragged portions of clothing, preserved meat tins, &c.

(p. 124) The handle of a rake brought home by Captain Ommanney from Beechey Island is much less weathered than the surface of Sir John Ross's stake...

Blue Book. 1852. 1852c/45229. Further Correspondence and Proceedings Connected with the Arctic Expedition. List of Penny’s relics: p. 120. Goodsir’s Cape Spencer notes: p. 114, Answer #8.

Hodder, Edwin. 1878. Heroes of Britain in Peace and War, Vol. 1.

Kane, Elisha Kent. 1853. The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin.

(p. 159) They told us, too, that among the articles found by Captain Penny's men was a dredge, rudely fashioned of iron hoops beat round, with spikes inserted in them, and arranged for a long handle, as if to fish up missing articles.

(p. 157) We were under weigh in the early morning of the 26th, and working along with our consort toward Beechy—I drop the "Island," for it is more strictly a peninsula or a promontory of limestone, as high and abrupt as that at Cape Riley, connected with what we call the main by a low isthmus. Still further on we passed Cape Spencer…

Markham, Clements. 1853. Franklin’s Footsteps.

(p. 62, footnote) Here also was found a long staff, with a cross piece attached to it. On the cross piece were lashed four bits of iron hoop, bent like hooks. For what this could have been used no one has been able to conjecture.

Ommanney, Erasmus. Journal written on HMS Assistance, 25 April 1850 to 31 August 1851. Glenbow Museum, Calgary.

(Aug 23, 1850) a ash pole with a cross head attached to it there from some hooks of bent iron --- apparently constructed for fishing

Potter, Russell A. 2016. Finding Franklin: The Untold Story of a 165-Year Search.

(RNE) Royal Naval Exhibition. 1891. Official Catalogue & Guide.

(p. 2) From Beechey Island— Pole, with a rudely-made Iron Rake, probably intended to rake up something from under water.

(RNE) Royal Naval Exhibition. 1891. The Illustrated Handbook and Souvenir.

(RNM) Royal Naval Museum. 1913. Catalogue of the Exhibits in the Royal Naval Museum, Greenwich.

Ross, W. Gillies. 2019. Hunters on the Track.

For Kane disputing Ommanney's sole discovery of Cape Riley, see Chapter 13 (Into Lancaster Sound), "A few years later, in his book The United States Grinnell Expedition..."

Not much further in this chapter is Forsyth concealing the news of Cape Riley from HMS North Star: "Off Bylot Island on the last day of August, the Prince Albert encountered HMS North Star, also on its way back to Britain..." Ross gives his source for this argument as Ian Stone's "Charles Codrington Forsyth (ca. 1810- 1873)" in Arctic 38, no. 4 (1985): 340-1.

(RUSI) Royal United Service Institution Museum. 1908. Official Catalogue of the Royal United Service Museum, 3rd Edition.

[Note: the 1st and 2nd editions of this catalogue seem to have been little more than the immediate early editions of the “3rd” edition, and are therefore unlikely to be of much value. However I cannot locate them; please contact me if you do. – LZ]

Savours, Ann. 1999. The Search for the Northwest Passage.

Snow, Parker. 1851. Voyage of the Prince Albert.

Snow, Parker. 1858. A Catalogue of the Arctic Collection.

Sutherland, Peter. 1852. Journal of a Voyage in Baffin’s Bay and Barrow Straits.

Walpole, Garth. 2017. Relics of the Franklin Expedition.

Woolwich, 1851, October 6. [Printed in The Times 8 Oct 1851, and many others.]

Captain Ommanney has brought home the first relic that was found by him of the traces of Sir John Franklin’s party at Cape Riley. It appears in the form of a rake, such as are used by persons employed in collecting sea-weed. The handle is about twelve feet long, and the gathering part about two feet six inches long, on which six teeth have been fixed about five inches each in length, formed of narrow hoop iron curved inwards.

Appendix 8: The sketch.

Where is the 1878 sketch from? The original identification was made in 2013 by Beatriz Garrido at RtFE, who helped Garth Walpole a number of times that summer (link1, link2) identify tricky relics sketches (for what would eventually become Walpole's book of relics). Garrido traced the sketch to The Sea (Vol 3) 1878 by Whymper.

However, the Whymper version doesn't mention the RUSI Museum location, and also lacks the numbered relics list. The only source I'm currently aware of that includes the numbered relic list is Edwin Hodder's Heroes of Britain in Peace and War, Vol. 1 – also from 1878.

I am tempted to call this ‘The 1878 Sketch,’ but it seems just as likely someone may discover it in an earlier publication.

Some versions of this sketch have a caption saying that these are McClintock relics. That is perfectly contradicted – without reference to the Rake – by the presence of the Beechey Island Anvil, a Penny relic.

Appendix 9: The relics in the sketches.

1. Anvil Block (Glenbow Museum, Calgary)

2. Portable Cooking Apparatus AAA2127.1

3. & 5. Inuit weapons and tools

4. Dipping needle AAA2223

6. Testament

7. Pulley block AAA2198

8. Medicine chest AAA2224

9. Chronometers AAA2203

• LZ notes: AAA2203 is the larger one, reading 4 o'clock. The other two resemble pocket watches (such as the five from the Boat Place, AAA2188-92), not the other two chronometers (Rae's 597 and Arnold 2020).

10. Snow-Goggles AAA2163

11. Knife and Spoon AAA2201 or AAA2207

12. Pemmican Canister AAA2196 (#31), Water-Can AAA2032 (presumably) (#12), &c.

13. Cylinder

• LZ notes: This seems twice as large as any of the Franklin Expedition cylinders I am aware of, and has writing on it.

14. Loaded Gun AAA2531 or AAA2612

15. Shot-Case AAA2169

16. Paddle AAA2194 (presumably)

17. Inuit spear

18. Fragment of Ensign AAA2128

Not listed originally/individually:

• LZ notes: This seems twice as large as any of the Franklin Expedition cylinders I am aware of, and has writing on it.

14. Loaded Gun AAA2531 or AAA2612

15. Shot-Case AAA2169

16. Paddle AAA2194 (presumably)

17. Inuit spear

18. Fragment of Ensign AAA2128

Not listed originally/individually:

21. Inuit bow

22. Spoon

24. Inuit snow knife

25. Inuit arrow

26. Pocket watch

27. Pocket watch

28. Jagged can

29. The Cape Riley Rake

30. Tea canister AAA2131

31. Pemmican Canister AAA2196 (mentioned in #12)

Numbered relic-for-relic 1878/1915 sketch comparison:

Numbered relic-for-relic 1878/1915 sketch comparison:

I count 31 relics total, two of which are in the 1878 sketch but not in the 1915 Players sketch: the tea canister (#30) and the pemmican canister (#31). The cylinder (#13) in the Players sketch, however, is very debatable if that's a cylinder at all.

Appendix 10: Cylinder

The cylinder in the 1878 sketch has two words written on the side. I can't figure out what they say. It's not the artist's name (that is in the lower right corner). It could be a badly mangled writing of "Record Tin." The size of this cylinder relative to the other relics in the sketch makes it much too large to match the known record tins, such as AAA2229, leaving open the possibility that this is a lost relic.

– L.Z. December 3, 2020.

– Update March 25, 2021. Alison Freebairn has pointed me to a first relic account contradicting Ommanney's, by Lt. Elliott: "I discovered the first traces myself. It was a piece of bottle found at Cape Riley. We searched further, and found a staff, iron bar, and other articles." A future updated version of this article will incorporate this detail. Also today have added the ILN reference for the "sighting of the graves" sketch (Nov 29 1851) and added the missing word "The" on one instance of Belcher's book title. A future update to this article will also point out that it's likely the rudely-fashioned hoop iron Rake would have been hammered out on the Anvil Block.