By Logan Zachary & Alison Freebairn. December 11th, 2024.

A warning: it is 20,000 words attempting to pin down 80 words, and would take hours to read through. The following excerpts briefly present some of the more interesting finds from the final installment.

EXCERPT: TORRINGTON’S “F”.

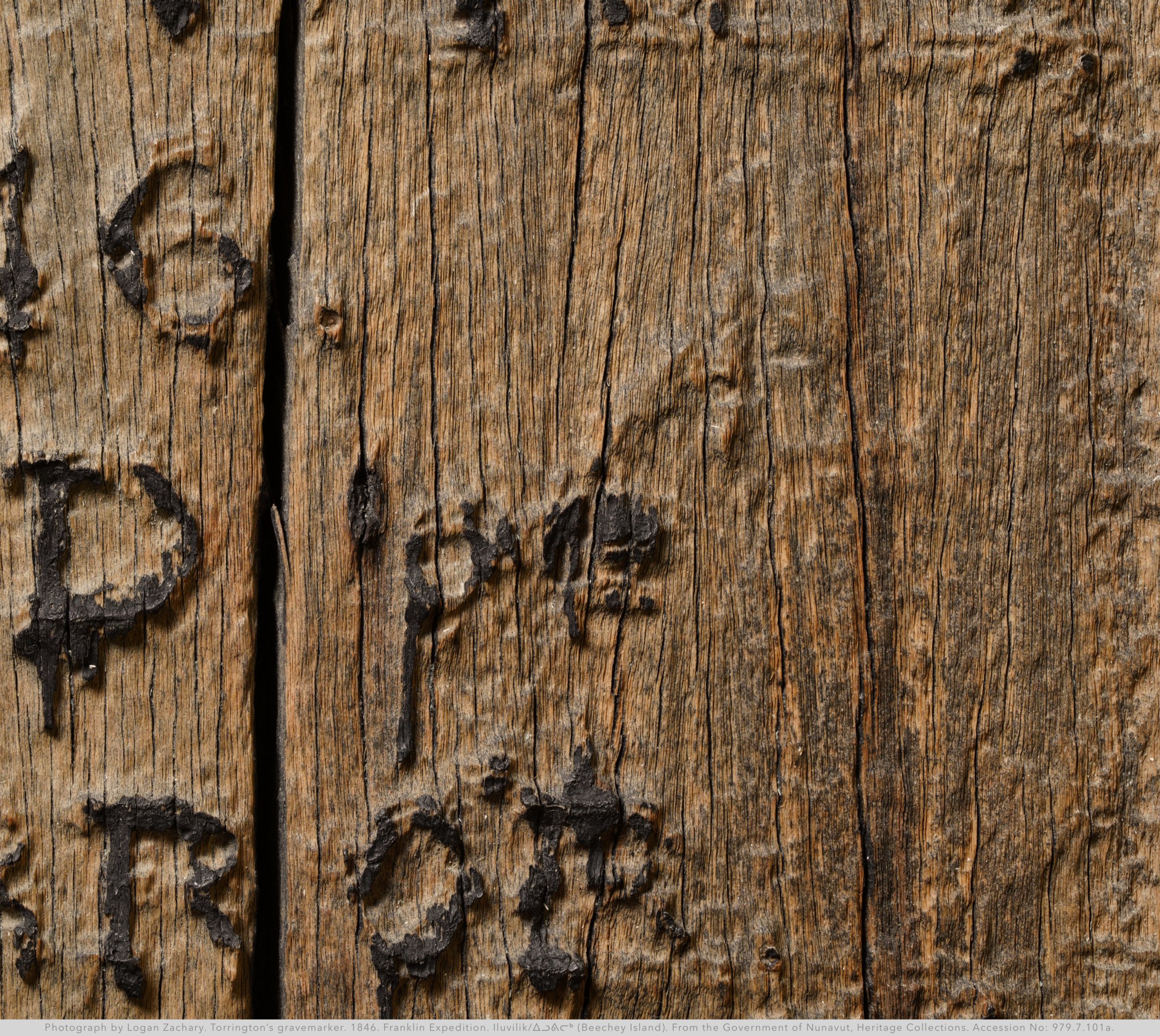

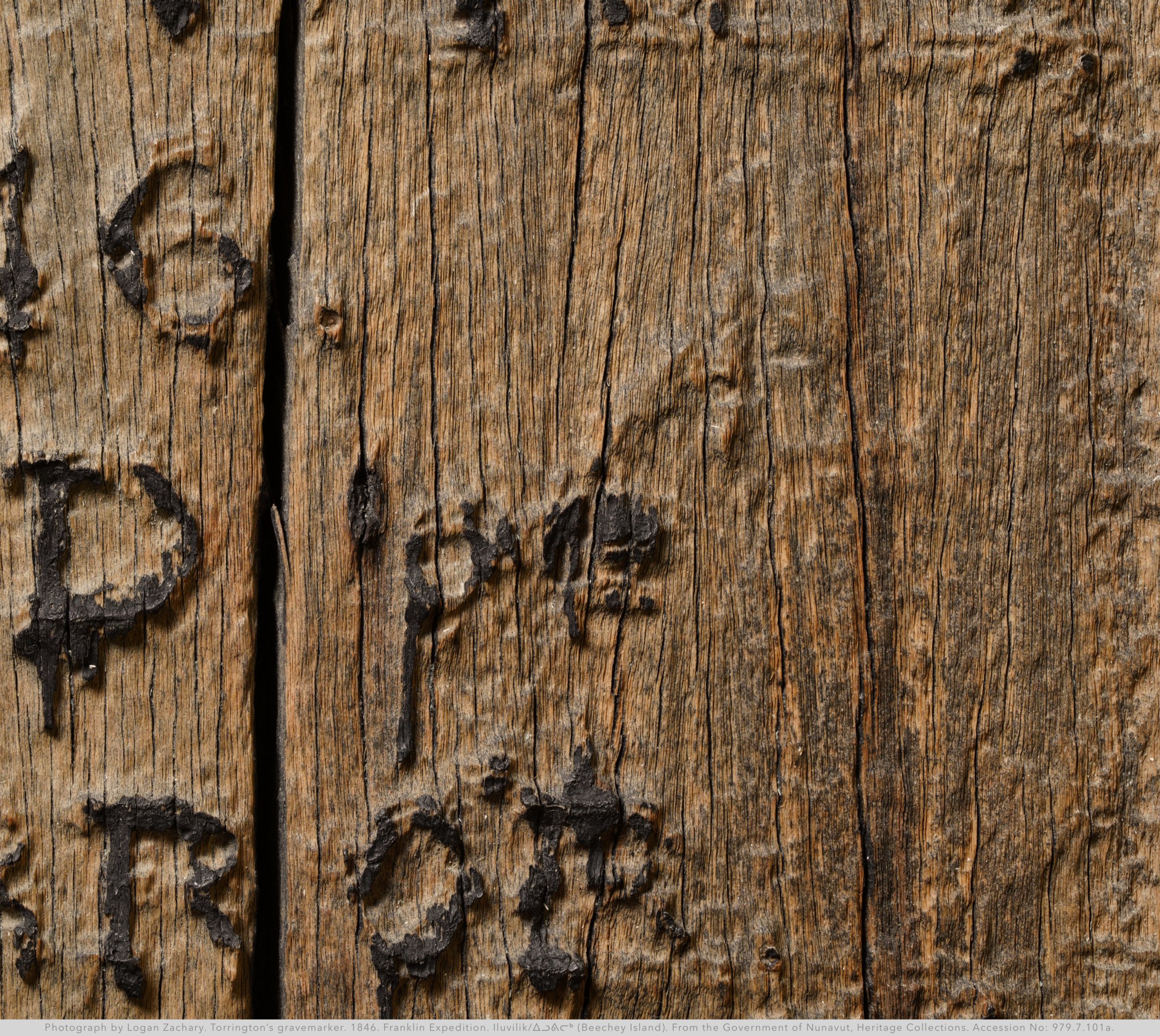

And here is the word photographed with a raking light:

By casting a raking light from one side, we can illuminate a previously hidden ridge on the gravemarker, matching the long swooping letter “f” from the Derbyshire photograph. And it indeed reaches down and touches the word “TERROR” beneath it.

* * *

* * *

* * *

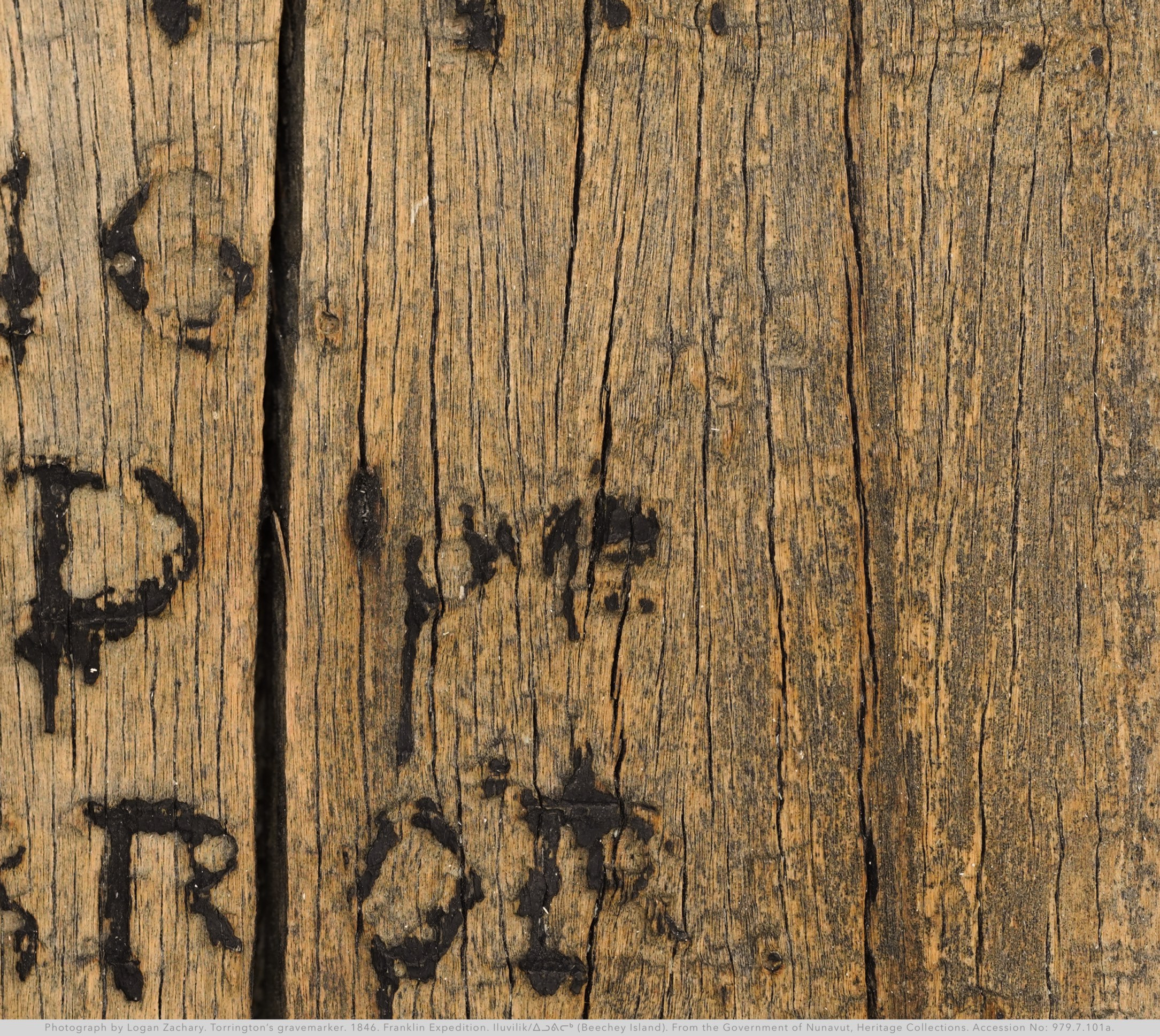

However, across that line, there are clusters of very small horizontal cuts – not half the width of your fingernail – with nothing apparent connecting them.

From that same highlighted section above, consider the following discrete area.

EXCERPT: TORRINGTON’S “F”.

…With all of these issues, how can we be certain that we are not looking at a well-crafted replica?

The Derbyshire photograph has revealed one unusual twist in the typography of the inscription, which may answer Powell’s question of authenticity for Torrington’s gravemarker.

{ Lines 8, 9 & 10. }

Torrington’s inscription tells us that he died “on board of HM Ship Terror,” with the words “on board of” set into a single line.

But that word “of” on the gravemarker does not resemble the word “of.”

{ Apostrophe “pe”...? }

We only know this word as “of” from the early transcribers. The final letter looks like an “e”. And indeed, a recent on-camera reading of the gravemarker’s inscription mistook this word as “the.” Interestingly, that is how A.P. Low had recorded the word as long ago as 1904: “ON BOARD THE HMS TERROR.”

However, nearly all the gravemarker transcribers of the 1850s recorded this little word as “of” (it is also the more grammatically correct reading, given the meaning of “H.M.S.”).

With the Derbyshire photograph, we can now observe how this word was originally written.

{ Derbyshire photograph vs. 2024. }

It is revealed to have been fairly unusual: it appears as the only lowercase word in the entire inscription — and with a long swooping stroke for the letter “f”. Indeed, the swoop of the stroke seems to reach down to touch the word “TERROR” in the next line.

Finally, taking this bit of knowledge back to the surviving gravemarker, we can look past the daub of black paint for the remains of the original letter.

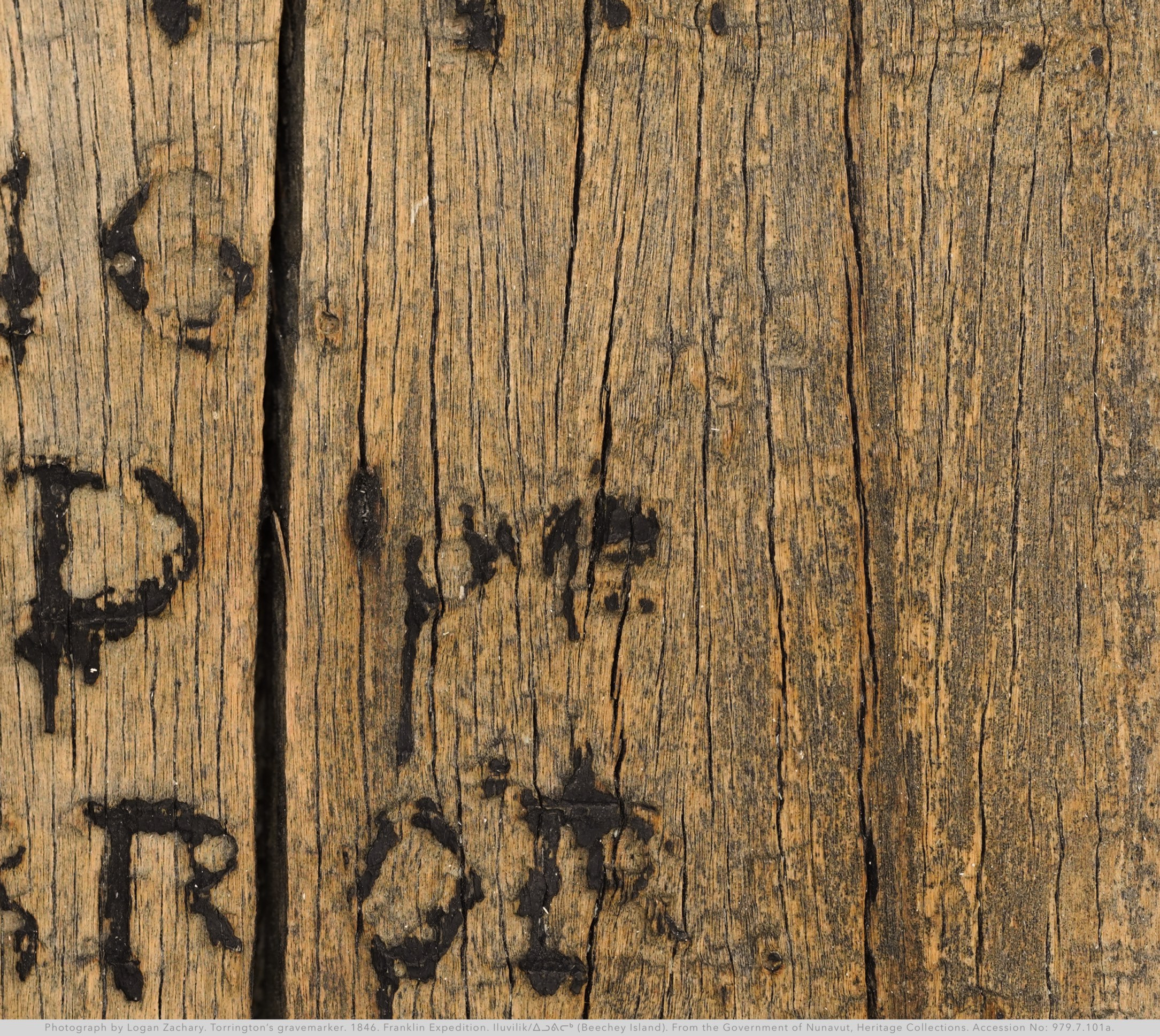

Here is the word photographed in direct light:

{ Direct light. }

And here is the word photographed with a raking light:

{ Raking light. }

By casting a raking light from one side, we can illuminate a previously hidden ridge on the gravemarker, matching the long swooping letter “f” from the Derbyshire photograph. And it indeed reaches down and touches the word “TERROR” beneath it.

{ The Derbyshire photograph. }

{ Left: Derbyshire photograph superimposed over the gravemarker. }

{ Right: raking light illumination of the lost letter. }

This is a critical survival. It could only have been identified now, with the Derbyshire photograph as a map pointing us to it. When would this letter have last been seen? The fact that the letter was apparently missed as early as 1904 (when Low recorded this word as “the”) would cordon off the 20th century, as well as some amount of time prior to 1904 as the letter began to fade.

We suggest that this is now the best answer to Powell’s question of authenticity regarding Torrington’s gravemarker: with the remains of that ridge still present – while also being hidden for at least 50 years, possibly more than 120 years – Torrington’s surviving wooden gravemarker has a claim to being as old as the Derbyshire photograph itself.

* * *

EXCERPT: WILLIAM BRAINE’S AGE.

…There is, nonetheless, a very good reason to believe that the same carpenter and crewmen did not create both Braine’s gravemarker and his coffin plate. They disagreed on his age. The gravemarker says that William’s age was 32, but the coffin plate says 33.

{ “Aged 32 Years”. }

{ “32”. }

We were unaware of anyone previously flagging this discrepancy, in the nearly forty years since the coffin plate was unearthed (cf. Beattie & Geiger 1987, Anonymous “Darling,” Lloyd-Jones 2004, Forst & Brown 2017). However, an essay by Torrington researcher Lauren Triola spotted the issue in 2019.

And this may not be a mere typo: Ralph Lloyd-Jones, in his 2004 paper on Franklin’s Royal Marines, wrote that William Braine “was either mistaken or he lied” regarding his age at enlistment. William had then given his age as 20 years old (at Christmas Eve 1833), but Lloyd-Jones believes he was born in March 1814, and was therefore only 19 — a difference of one year.

And so, for some reason, this strange discrepancy was echoed in death. In William’s two inscriptions on Beechey Island, the one above ground said he was 32, but the one below ground said he was 33.

{ “33”. Photograph courtesy of Owen Beattie. }

* * *

EXCERPT: DATING THE DERBYSHIRE PHOTOGRAPH.

…A combined conclusion would therefore be that the Derbyshire photograph was taken after T.C. Pullen’s 1853 repainting: that Pullen’s repainting had been done with the intention to not modify anything about the original inscription (“4Part”), but that as a later repainting it did produce one unintentional error (“Chis day”).

{ ▽ Left: Derbyshire. Middle/Right: McClintock, August 1854. }

{ McClintock’s photographs courtesy of Douglas Wamsley. }

Such an idea, combined with the Derbyshire photograph’s basic similarity in appearance to McClintock’s two known 1854 Beechey Island photographs (above; Wamsley & Barr 1996) — as well as the lack of snow on the island in those same photographs — suggests that the Derbyshire photograph was most likely taken during August of 1854 by Leopold McClintock.

This is a very thin chain of logic, but plausible. It is, for the moment, a stronger overall argument than the fact that the Derbyshire photograph was tipped in to a scrapbook amidst newspaper clippings from 1851 (which are themselves out of order; left to right: November, June, September).

Hopefully the future will bring more evidence to bear on this topic.

* * *

EXCERPT: BRAINE’S MISSING INSCRIPTION.

…Here, we would hope to be able to turn to the original wooden gravemarker for a third opinion.

But in 2017, while Hansen identified the remains of this line, he concluded that “no letters are readable.” Attempting to use the Derbyshire photograph as a map, in 2023 we were only able to improve on that assessment with a single word: from the closing “...whom ye will serve”, the word “will” is still just discernible when a raking light is cast across it.

{ The remains of “will” (line 9). }

The letters are faint, but they are in the correct position indicated by the Derbyshire photograph (just down diagonally from the last letter of the word “Years” in the line above).

Having exhausted what a flashlight at a shallow angle could do, even with the aid of the Derbyshire photograph, we believed the search was over. However, months after having left Canada, in the summer of 2023 we found in our photographs a new method for reading the Beechey gravemarkers.

{ Letters written with (black) and without (red) serifs. }

{ Serifs marked in red. }

A serif is an extra flourish to a letter, a small extra mark at the end of a primary stroke. Not all typefaces have serifs, but it is evident from the Derbyshire photograph that the Beechey gravemarkers used serifs extensively. They may well have been useful in establishing a boundary from which a letter could be carved out — thus making them the deepest cuts of all into the wood.

The photograph below spotlights where line 9 (Braine’s Bible verse) should be. The word “will” is on the far right. Here a search for other readable words and letters – even with a flashlight at a shallow angle – was defeated by the irregular deterioration of the wood.

{ Line 9 spotlighted. }

However, across that line, there are clusters of very small horizontal cuts – not half the width of your fingernail – with nothing apparent connecting them.

{ Three small horizontal cuts. }

For some reason, they all exhibit a slight orange hue. That bit of color was what first caused us to notice them.

Individually, they appear unconnected and random. And so we initially ignored them, amidst the many other various marks on the aging gravemarker.

But when these particular little orange cuts are separated out as their own group, their distribution does not seem random.

{ Line 9 horizontal cuts circled. }

From that same highlighted section above, consider the following discrete area.

{ Section of line 9. }

Here the irregular contours of the wood defeat the ability to recognize where the primary strokes of the letters once were, even with the use of a flashlight.

But with an eye towards focusing on potential serifs, this picture changes.

{ Potential serifs circled. }

When considered as serifs, one can convincingly draw in the missing letters. This is now a game of “connect the dots.” Most readers will have already guessed the solution to this word: this is “whom” from “Choose you this day whom ye will serve.” Knowing this, some diagonal cuts from the letter “w” are still discernible.

Meanwhile the letter “o” is today invisible, as that letter would naturally lack serif marks.

{ “whom” serifs. }

Thus a lost word from Braine’s Bible verse, unrecognized by Hansen in 2016 and ourselves in early 2023 — even with the Derbyshire photograph in hand — can be recovered by finding and connecting the remains of these tiny cuts.

Having identified “whom” and the word “will” earlier above, we can now look between these words to identify one of the two contested pronouns from Braine’s Bible verse…

* * *

End of excerpts preview. Link to full article (link).