Entries by Logan Zachary. 2018–2022.

A Bestiary of Victory Point Record Facsimiles.

Who Wrote the Victory Point Record?

Lost Letters of the Victory Point Record.

Tuesday / After.

Fingerprint.

Underlined All Well.

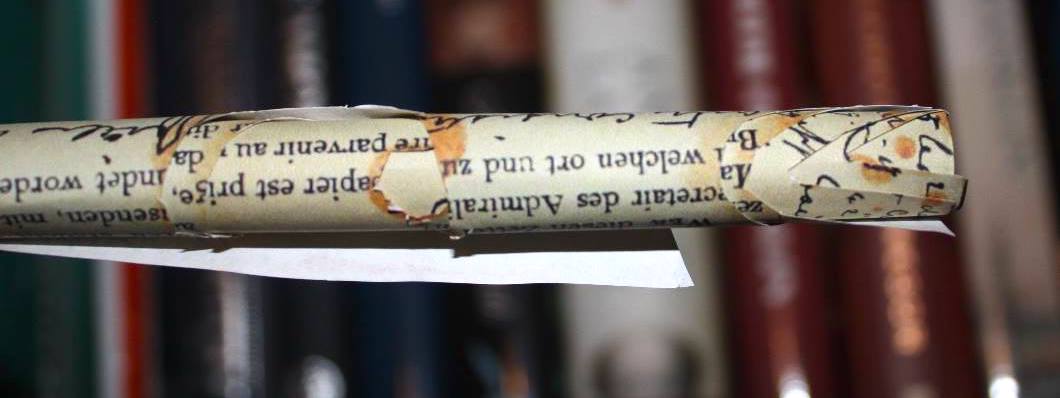

Cylinders.

Transcript.

* * *

A BESTIARY OF VICTORY POINT RECORD FACSIMILES

The 1859 Netherclift was used again the next year for the 2nd edition of The Voyage of the Fox. It was replaced at the end of the decade for the 3rd edition (1869), with a new facsimile by Netherclift.

WHO WROTE THE VICTORY POINT RECORD?

LOST LETTERS OF THE VICTORY POINT RECORD

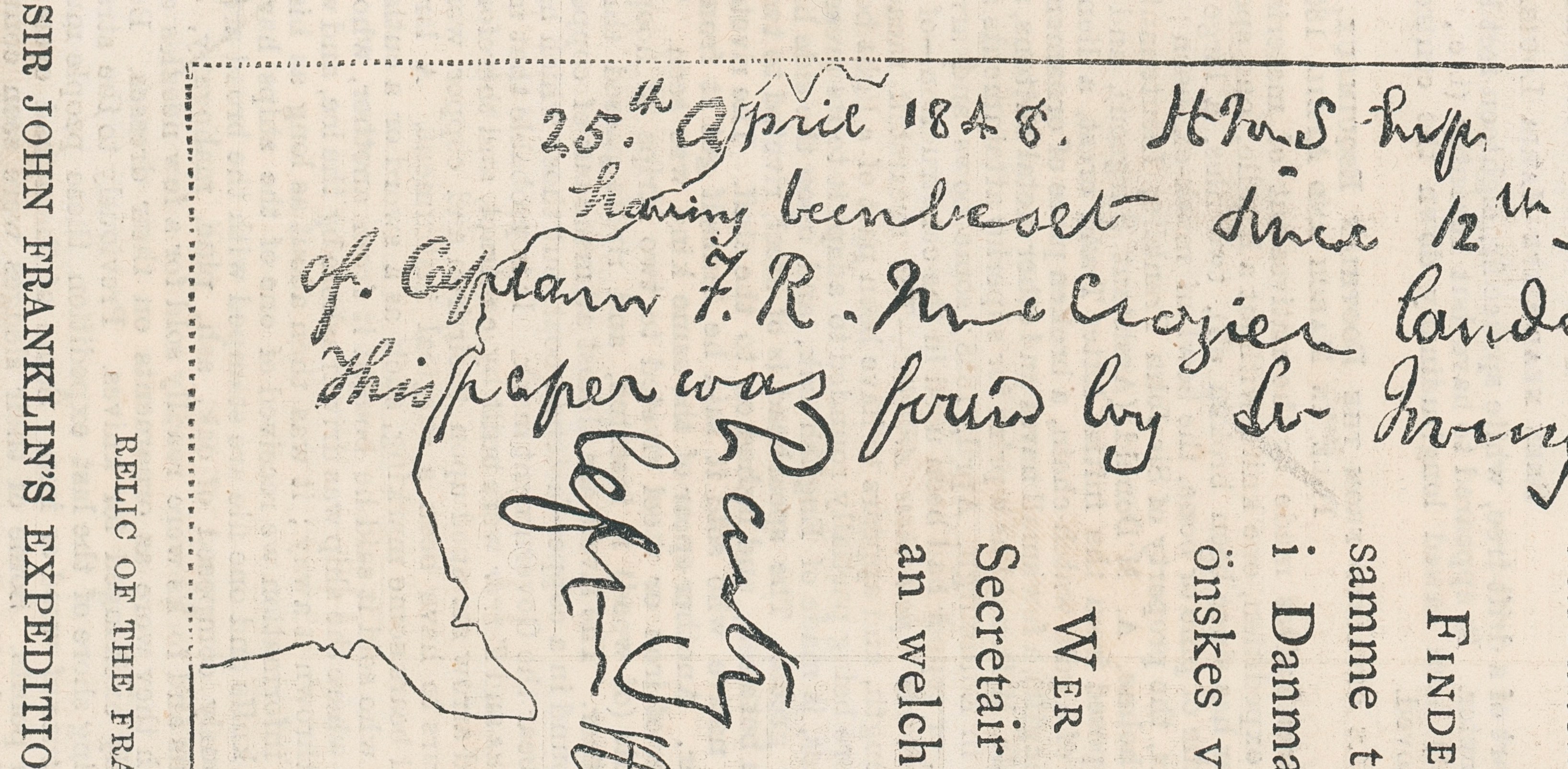

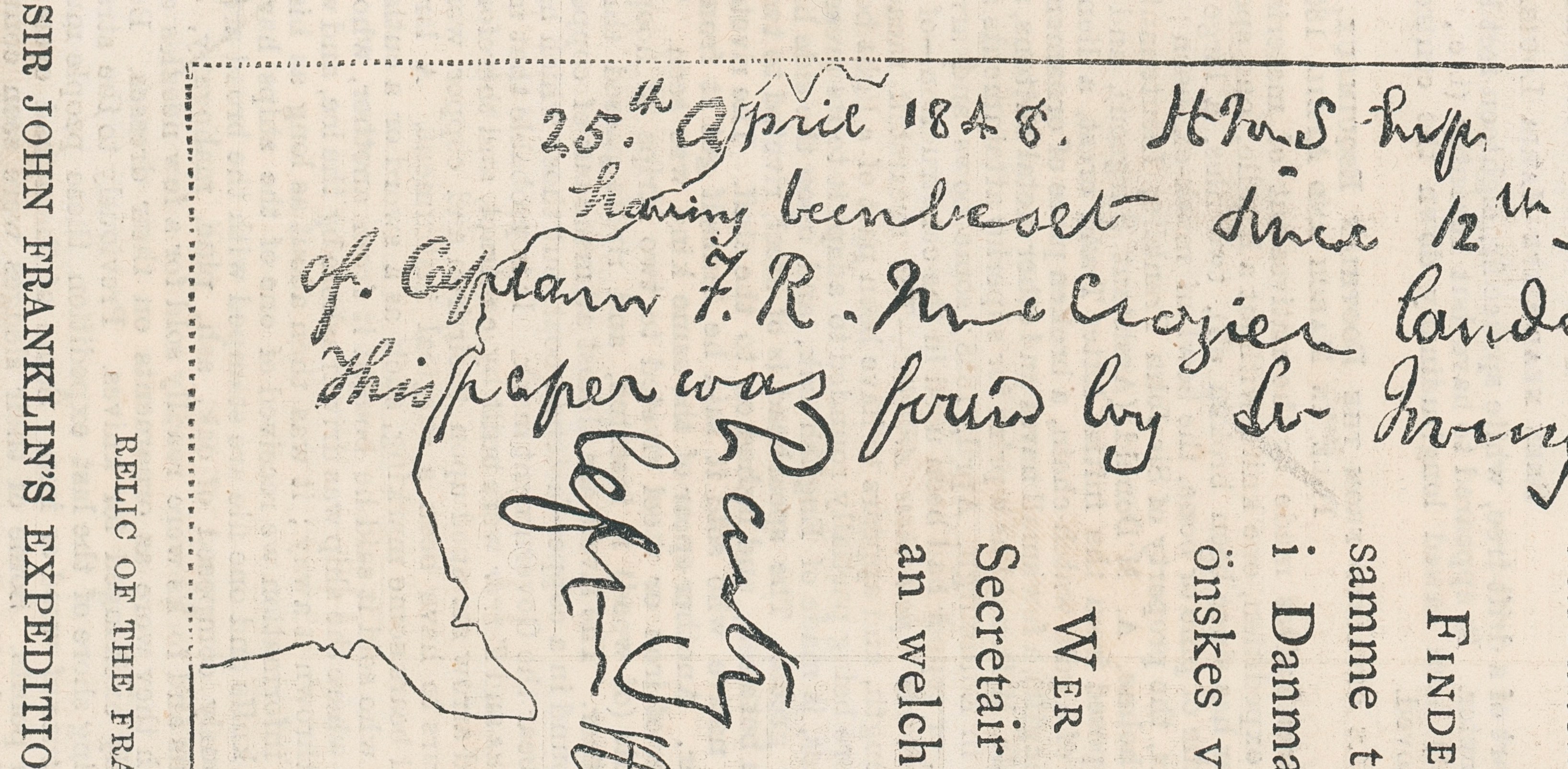

A rare early photograph of the Victory Point Record, dated about 1859, by John Powles Cheyne. (Click pic for full resolution.)

It is so early that we can see letters of words that have rotted away since the note’s discovery.

Two little ‘chimneys’ near the damaged corner have gone missing. The right chimney is only visible on certain Cheyne #12 slides (such as Greenwich’s, above). But the left chimney is the important one.

“…the words ‘All well’ were not underlined.”

– Cyriax on the Gore Point Record (“The Two Franklin Expedition Records,” The Mariner’s Mirror, 1958).

I believe this remark by Cyriax was an error, causing an unnecessary amount of speculation on why the VPR’s All Well is underlined while the GPR’s is not. Zooming in on the publicly available image of the Gore Point Record, I can see a faint underline there. It is very faint – but it is faint just like the letter “p” in “Expedition” above it. The ink seems to have run out on the last letter “L” of “well”, just before Fitzjames drew the underline stroke.

Now that Regina Koellner has located the ‘3rd Note’ or Disko Bay Record (link), we can see that this All Well did not have a Fitzjames underline. On the other hand, this All Well is (unlike the other two) already sitting on a printed line, being several lines higher on the Admiralty form.

CYLINDERS

TRANSCRIPT

Commander.

Every now and then one of these [Victory Point Record] reprints, believed to be the original, is sent to the Admiralty by someone who considers it to be of great importance. I believe that the Scottish police once telegraphed that they had arrested, on general principles, the bearer of one of these documents, and were “holding him pending the receipt of Admiralty instructions.”– Rupert Gould, from a footnote in Oddities (1928).

The history of the Victory Point Record is intertwined with its facsimiles, the medium by which nearly everyone reading these words first encountered the document. This is not due simply to the limitations of Victorian printing. The words forever lost to the lower left corner damage, and those heavily obscured by stains, have forced every discussion of the VPR to resort to a facsimile.

In an alternate reality where the original Victory Point Record had been lost or stolen from the RUSI Museum, the evaluation and ranking of these facsimiles would be the scene of ferocious study and debate.

As it is, to my knowledge no one has ever written a study of these documents. The name “Netherclift” – the man who created the most accurate of all VPR facsimiles – has been forgotten. Two basic questions have gone unanswered: which VPR facsimiles are derived from the original, and which is the best.

{ Establishing family relations. }

I have presented no evidence for my conclusions here. The evidence I observed was overwhelming, but displaying it would also be overwhelming, requiring dozens of handwriting comparisons for each facsimile. I am therefore making all images available for anyone wishing to conduct their own investigation. A quirk or a squiggle is invented in one facsimile, a range of these are identified in that document, and then they either appear or disappear in the next facsimile, creating a straightforward “family tree” of identifiable idiosyncrasies.

What follows will be brief remarks on some of the most noteworthy early VPR facsimiles. Each image is clickable to download at high resolution.

{ The Illustrated London News facsimile. }

The Illustrated London News facsimile was the first mass-market facsimile of the Victory Point Record. For the British public unable to travel to the RUSI Museum in London, this was the VPR they first saw, held, and read.

In terms of handwriting and design accuracy, it is one of the least accurate. Its virtue was in its speed: it appeared in the Illustrated London News on October 1st 1859, just a week after the Fox had reached London.

Nevertheless it became the mother of future facsimiles, such as the American Harper’s Weekly facsimile (see next entry) — and even the VPR facsimile in Franklin searcher Carl Petersen’s 1860 book (link to image).

Technically, the Illustrated London News’ facsimile must share 1st Place with that same day’s issue of the Illustrated Times, an upstart rival newspaper. However it is unlikely that the ILN felt threatened: in addition to significant handwriting and design issues, the Illustrated Times’ VPR facsimile even gets a few words wrong — a rare sin.

{ Corner of the ILN facsimile. }

The ILN facsimile also made one extra move that put it ahead of the competition: it includes – in a script slightly faded – some inferred letters that are missing from the lower left corner. Given that this makes the document actually readable, it is unfortunate that this strategy wasn’t adopted for the Netherclift facsimile in McClintock’s book a few months later.

{ The Harper’s Weekly facsimile. }

The Harper’s Weekly facsimile. This is a facsimile of a facsimile: the United States newspaper Harper’s Weekly copied the Illustrated London News’ facsimile from earlier in the month, without crediting them. Thus it retains all the ILN’s errors, while adding several novel inaccuracies of its own. It is one of the least faithful VPR facsimiles ever made.

Surprisingly then, it holds a unique distinction: front page news, right under the masthead — an honor not given to the VPR by any British newspaper, and a bellwether of the coming American-led phase of ‘The Search.’

{ The 1859 Netherclift. }

The 1859 Netherclift facsimile, from McClintock’s expedition book. This facsimile was created shortly after the VPR returned to London. McClintock landed in late September, and this facsimile appeared published in his book, The Voyage of the Fox in the Arctic Seas, before the end of December.

Two names at the bottom hint at its creation: in larger print, John Murray, publisher of The Voyage of the Fox, and then in smaller italics, Joseph Netherclift, a facsimile specialist. Murray the publisher would have contracted Netherclift the facsimilist to create this work, and he could hardly have chosen better. When compared to the original Victory Point Record, Netherclift’s 1859 facsimile is painstakingly faithful — more accurate than all VPR facsimiles before and since. Where other versions are content to merely appear similar, the Netherclift places nearly every stroke of Fitzjames’ handwriting just as it was drawn on the original document.

When we consider that the VPR’s stains were slowly spreading, and that handwritten fragments were continuing to fall off (see “Lost Letters” elsewhere on this page), the 1859 Netherclift having come so early in the VPR’s history makes it a primary source for studying the original document itself.

Indeed, many later “Victory Point Record facsimiles” are likely just facsimiles of the 1859 Netherclift. (One from 1877 will be identified further in this article.)

{ The 1859 Netherclift inside The Voyage of the Fox. }

One aspect of the 1859 Netherclift’s accuracy is seen above: its faint but distinctly blue tint, as compared to the pages surrounding it in The Voyage of the Fox.

The Victory Point Record held in Greenwich today is a thoroughly warm-toned document, a mix of yellows, oranges, browns, and reds. But early sources reported the document as being blue in color. I’ve found one attestation of this as late as 1891, from a review of that year’s Royal Naval Exhibition in London:

The most touching relic is the last record written by the survivors, brown faded writing meandering round the margin of the blue official folio, which, after lying for years immured in the frosty darkness of a cairn within the Arctic circle, was brought home and lies here now...[The Evening Telegraph, 21 July 1891.]

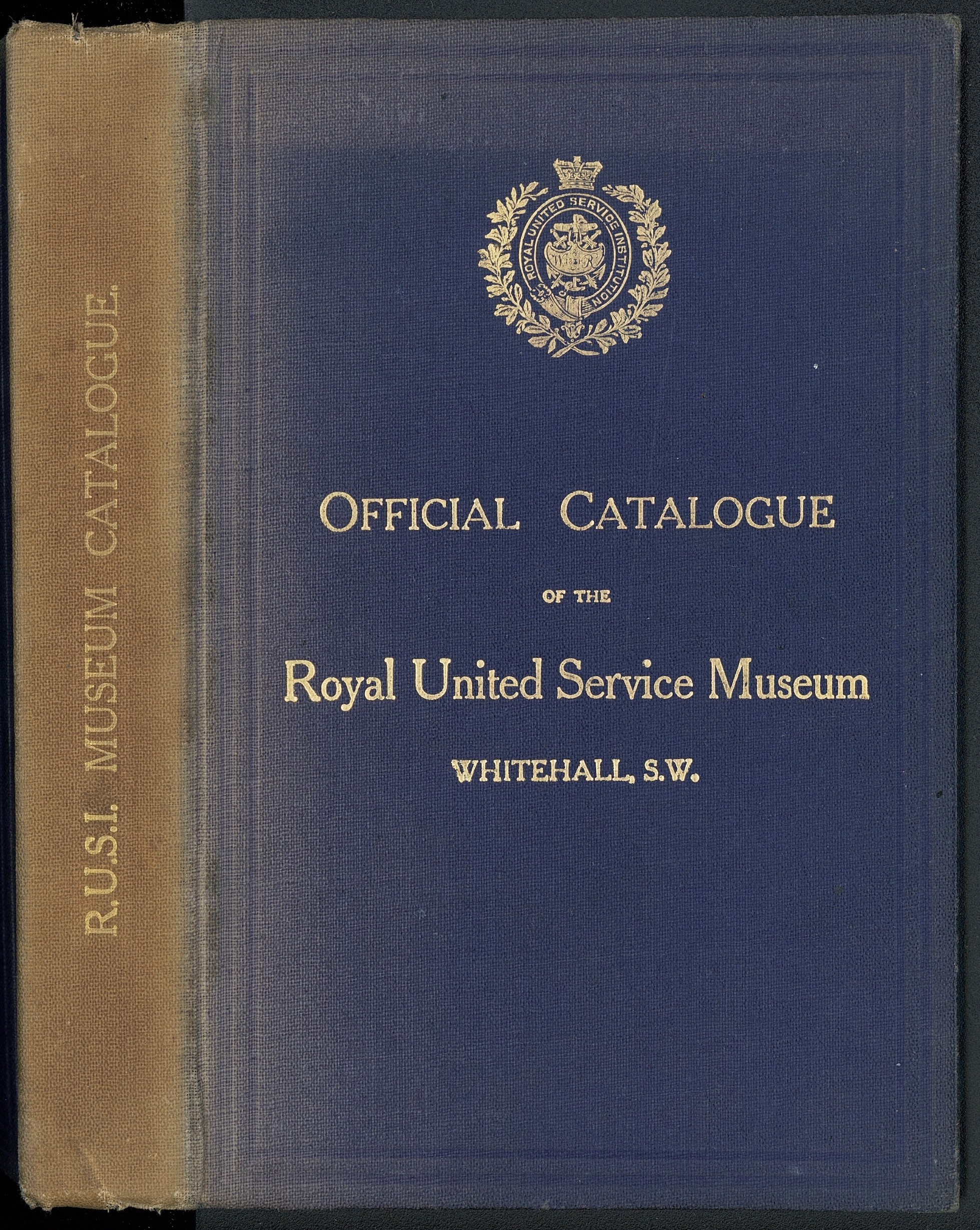

Below is my copy of the RUSI Museum’s 1908 catalogue. It is an ideal example of a blue having turned to brown where exposed to light. As the original VPR was still blue in 1891 – 30 years after its recovery – this may indicate that it was thereafter exposed to sunlight somewhere in London.

{ 1908 RUSI Museum catalogue with faded spine. }

The 1859 Netherclift was used again the next year for the 2nd edition of The Voyage of the Fox. It was replaced at the end of the decade for the 3rd edition (1869), with a new facsimile by Netherclift.

{ The 1869 Netherclift. }

The 1869 Netherclift appeared a decade after the original, inside the 3rd Edition of The Voyage of the Fox. It begins a new tradition: highly accurate faux stains, matching the positions of those on the original Victory Point Record.

McClintock writes in a new footnote that, “The stains upon the record—as represented in the facsimile—were caused by the rusting of the tin cylinder in which it was contained.”

In addition to the year in the footer turning over to 1869, Netherclift’s initials are not the same.

{ The two Netherclifts. }

“Netherclift” has changed from father to son: from Joseph Netherclift in 1859 to Frederick George Netherclift in 1869. In the Oxford English Dictionary (e.g., 1901), the term “facsimilist” points to an early usage of the term regarding this same Frederick George:

Netherclift’s Handbook To Autographs.Mr. Netherclift, who is well known as a facsimilist and as an “expert” in handwriting, has just finished the serial publication of a work of rare interest.[The Saturday Review, XIV, 11 Oct 1862, p. 453.]

As well, it was this Frederick George Netherclift who first identified the name “Peglar” in the famous ‘Peglar Papers’ — as credited by McClintock in the 1869 edition of his book:

...by the aid of chemical re-agents, Mr. F. G. Netherclifft [sic], of 32 Brewer Street, Golden Square, has been able to decipher the name of Hy. Peglar, together with several particulars respecting him — stature, 5 ft. 7¼ in.; hair, light-brown, &c.[The Voyage of the Fox, 3rd edition (1869), p. 310.]

Given the accuracy of the stains on the 1869 Netherclift facsimile (and, tangentially, the breakthrough on the Peglar Papers), we can be certain that Netherclift (the younger) must have returned to the original Victory Point Record. Surprisingly then, the 1869 Netherclift facsimile is ever so slightly less accurate than its predecessor, that credited to his father from 1859. Wherever an 1869 stroke deviates from the 1859 version, consulting the real VPR shows the elder 1859 Netherclift to be the more strictly accurate facsimile.

In spite of this, in articles and visual presentations on the Franklin Expedition today, the 1869 Netherclift is regularly mistaken for being the actual Victory Point Record — I’ve even seen it given a copyright acknowledgement to Greenwich.

Future editions of McClintock’s book would continue to use the 1869 Netherclift (as would, notably, Nourse’s 1879 book on Hall’s search). The 1869 Netherclift from The Voyage of the Fox’s 4th edition below, published in 1875, in particular retains its original blue coloring. If the other editions have merely faded, then this (below) might be our most accurate view of the original colors from the Victory Point Record — a strikingly different appearance from the document we are familiar with today.

{ The 1869 Netherclift, printed in 1875. }

{ The 1877 McClintock portrait facsimile. }

At a glance, the above Victory Point Record facsimile from 1877 seems to be just another accurate, comfortably readable VPR facsimile.

Stepping back reveals how unusual it is.

{ The 1877 McClintock portrait. }

It was not intended to be a facsimile for reading. It is merely one relic in a sketch of other relics recovered by McClintock’s search — and all merely to embroider the lower third of a portrait of Captain McClintock.

To my knowledge, this is the only relics sketch that includes the VPR as one of the relics. It is somewhat startling that no one before or since thought to depict it like this.

Nor is the content of the VPR merely hinted at. Despite dropping a single word (“is,” lower right corner), the entire document is otherwise perfectly readable, from All Well to Backs Fish River. Even the handwriting is extremely accurate to Fitzjames’ original handwriting.

And this is astonishing when we consider its size. You can cover this Victory Point Record with a few coins from your pocket.

{ Locket-sized. }

Fitzjames’ handwriting is even smaller than the smallest writing on these coins. This locket-sized VPR from 1877 is only 3 inches high. The tiny “All Well” could fit onto the crown on Elizabeth’s head, or as a neck tattoo for George.

The portrait with facsimile was produced for Arctic Expeditions from British and Foreign Shores by D. Murray Smith, the print credited to McFarlane & Erskine Lithographers Edinburgh. But as impressive as this accurate, legible, miniature VPR is, we can not give McFarlane & Erskine credit: their 1877 facsimile is, in fact, stolen goods. A close inspection reveals this to be an outright copy of a facsimile we examined earlier. In every stroke, it is the excellent 1859 Netherclift.

– L.Z. March 27, 2022.

Special thanks to Douglas Wamsley, for generosity with his knowledge and his polar library.

Updated April 6, 2022. Added the detail about F. G. Netherclift identifying the name Peglar.

* * *

WHO WROTE THE VICTORY POINT RECORD?

{ The four hands that wrote the Victory Point Record. }

{ Fitzjames, Crozier, Gore, and Des Voeux. }

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London }

The author of both notes written on the Victory Point Record (1847 & 1848) was James Fitzjames, Commander/Captain of HMS Erebus. Gore and Des Voeux added their signatures in 1847, and Crozier added the critical closing remark to the 1848 note.

These attributions seem to be well known and unchallenged today. What I have not seen remarked upon is how and when the identification of Fitzjames as the author of the two notes was reached. Fitzjames only signed the 2nd note — not the 1st in 1847. Even R. J. Cyriax, in both his landmark 1939 book and his 1958 study of the VPR, credits Fitzjames without a source. [1939: “The other entries, except the signatures, were written by Commander Fitzjames.” 1958: “Both the entries on these records are in the handwriting of Commander James Fitzjames.”]

An obvious early source to cite would be McClintock’s The Voyage of the Fox in the Arctic Seas, which states that: “With the exception of the signatures, and the note stating when and where they were going, which was added by Captain Crozier, the whole record was written by Captain Fitzjames.” As leader of the expedition that discovered the Victory Point Record, McClintock’s assertion carries some authority. But there is an odd comment in that same book, where McClintock contradicts his own assertion.

Tugging on this thread will reveal who McClintock’s own source was.

The odd contradiction comes just one page after the attribution of “the whole record” to Fitzjames. Regarding the difference between the 1847 and 1848 notes, McClintock wrote:

In the short space of twelve months how mournful had become the history of Franklin's expedition; how changed from the cheerful “All well” of Graham Gore!

“The cheerful “All Well” of Graham Gore.” If McClintock believes that Fitzjames wrote the record, then why does he attribute “All Well” to Gore?

To understand where this line came from, I compared the half-dozen different editions of McClintock’s book. The answer lay in the first two editions of The Voyage of the Fox, from 1859 and 1860 respectively.

In his book’s first edition (1859), McClintock in fact believed that the VPR’s first note was “apparently by Lieutenant Gore” — not Fitzjames. Presumably he believed this as Gore’s signature appears first at the conclusion of the 1847 note. Fitzjames’ own signature is not on the 1st note at all. Thus in 1859, McClintock did indeed believe that the words “All Well” had been written by Lt. Graham Gore.

Regarding the 2nd (1848) note on the VPR, McClintock wrote: “This marginal information was evidently written by Captain Fitzjames, excepting only the note stating when and where they were going, which was added by Captain Crozier.” In all instances, McClintock in 1859 attributes each note to the signature that appears at each conclusion: first Gore, then Fitzjames, then Crozier.

Then in the following year (1860), a second edition of McClintock’s book was published. None of the above wording had changed – but an asterisked footnote was appended to the attribution of “apparently by Lieutenant Gore*”:

* Since the appearance of the first edition of this narrative I have been assured (by John Barrow, Esq.) that this part of the record is in the handwriting of Captain Fitzjames. That it should appear different from the marginal addition of 1848, which bears Fitzjames’s signature, may be accounted for by the peculiar circumstances of privation and exposure under which the latter was written.

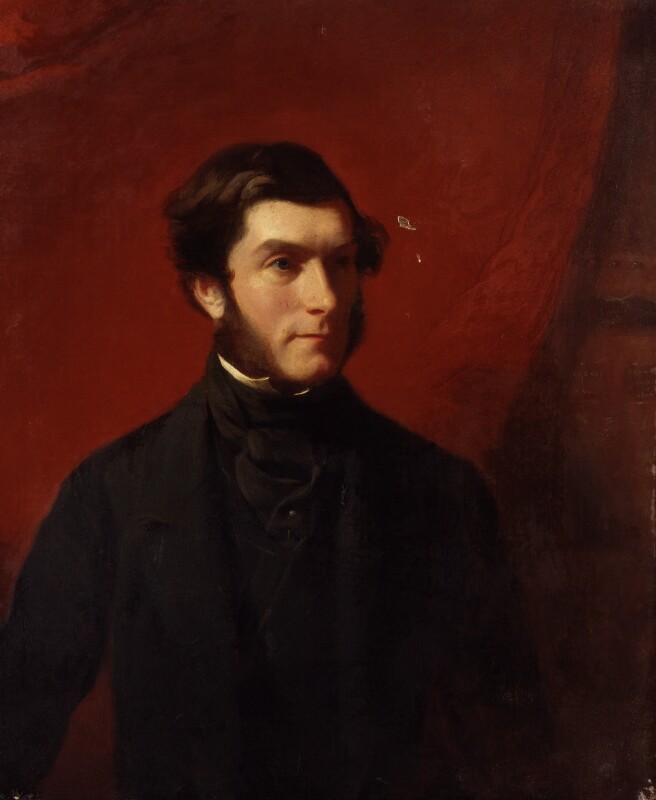

John Barrow, Esq. Here, then, is the story. Fitzjames’ authorship of the 1848 note was recognized from the start, as his signature both matches and concludes that note around the margins. But it was Fitzjames’ friend John Barrow Jr. — son of the famous Second Secretary — who recognized Fitzjames’ handwriting on the VPR’s opening 1847 note, and convinced McClintock of the fact.

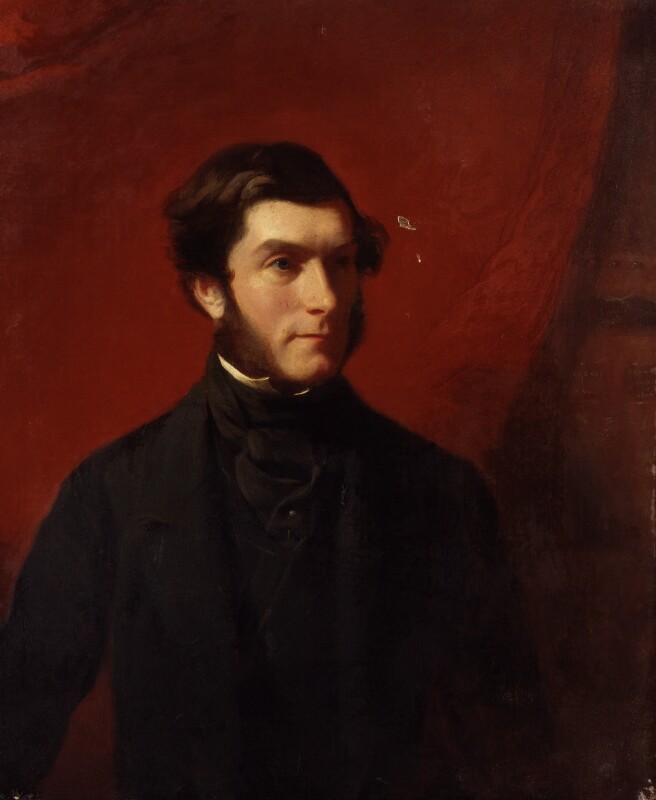

{ John Barrow by Stephen Pearce, oil on millboard, circa 1850. }

John Barrow Jr. would certainly know Fitzjames’ hand. The correspondence from their friendship forms a critical source for William Battersby’s biography of James Fitzjames, a friendship Battersby estimated to have begun around 1838. James Fitzjames’ final surviving letter, written as Erebus and Terror stopped at Disko Bay, was to John Barrow Jr. (11 July 1845). And it was Barrow who identified James Fitzjames’ handwriting on Beechey Paper #2 (link) and the Disko Bay Record (link), his initial on both identifications in Admiralty records.

Strangely, then, this handwriting citation to John Barrow Jr., the friend and correspondent of James Fitzjames, disappears from the 3rd edition of McClintock’s book. And meanwhile, as we have seen, an artifact of that early confusion stayed lodged in place: “the cheerful “All well” of Graham Gore.” Even when McClintock passed away in 1909, that strange line was still there in the most recent (1908) edition of The Voyage of the Fox.

An error that has survived that long should probably be left alone. In this instance, it serves as the breadcrumb trail of a misattribution from half a century earlier, to a critical footnote that appeared in the 2nd edition and then vanished in the 3rd.

For additional information:

Alison Freebairn’s “John Barrow Junior, the Quiet Hero of the Search for Franklin” at Finger-Post.blog (link).

The two works by Cyriax referenced: 1939’s Sir John Franklin’s Last Arctic Expedition and 1958’s “The Two Franklin Expedition Records Found On King William Island” (in The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 44, No. 3, Aug 1958).

– L.Z. June 1, 2021.

* * *

A rare early photograph of the Victory Point Record, dated about 1859, by John Powles Cheyne. (Click pic for full resolution.)

It is so early that we can see letters of words that have rotted away since the note’s discovery.

|

| Tasmanian Archives: Jack Thwaites Collection; NS1155/1/20 / © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London |

These letters are not new to us; they were carefully recorded at the time. They were used to infer additional words that – even then – were missing from the VPR’s damaged lower left corner.

|

| Illustrated London News facsimile of the Victory Point Record, 1 Oct 1859, p. 327 |

This newspaper facsimile shows how the lost fragments reconstructed additional words. With Cheyne’s photograph, we can see the original James Fitzjames handwriting with which the Victorian searchers completed these sentences.

* * *

I received this early photograph after requesting that the Tasmanian Archives digitize their Cheyne Stereographic Slides set, as part of a series on Cheyne that I’ve been writing. The Victory Point Record was #12 in Cheyne’s photography of the new McClintock relics from 1859.

At first I considered Cheyne’s VPR photograph to be of little interest, as Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum has published its own (modern, well-lit) photograph of the VPR.

Recently I did a closer comparison, seeing that Cheyne’s photograph shows fragments of the Victory Point Record that have since been lost.

“HMShips” has lost half of what had originally survived. The upper portion of the “B” in Erebus is rotted away.

|

| Tasmanian Archives: Jack Thwaites Collection; NS1155/1/20 / © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London |

In the corner, the “–tain” of Captain has completely vanished. This was part of Fitzjames’ first mention of Captain Crozier in the document, now as expedition leader: “…105 souls under the command of Captain FRM Crozier…”

Below it, the downstroke on the first letter of “paper” is gone. “This paper was found by Lt. Irving…”

|

| D2184, F6214 © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London |

Two little ‘chimneys’ near the damaged corner have gone missing. The right chimney is only visible on certain Cheyne #12 slides (such as Greenwich’s, above). But the left chimney is the important one.

|

| The 1859 Netherclift facsimile (courtesy Alison Freebairn) |

During a comparison of VPR facsimiles last year, I noticed that the 1859 Netherclift puts a fragment of handwriting underneath that left chimney – a curved line. No other facsimile records this. If accurate, the word in that position would be “April.”

And compared to all others, the 1859 Netherclift is extremely accurate. The Netherclift was the VPR facsimile included in the first edition of McClintock’s expedition book, The Voyage of the Fox in the Arctic Seas (published in December 1859). It is possible that this curved line was only legible immediately after McClintock’s expedition returned to London. [Indeed, Netherclift’s own later 1869 facsimile omits this bit of curved handwriting.]

Was the handwriting lost when that ‘chimney’ piece broke off? Could it still be hanging on? I tried to see it in person at Greenwich, but the area is too dark. A conservator at Greenwich would have to use a light from beneath, or some other method, to determine it if it’s still there. [If it’s ever found and recorded, there is an easy handwriting comparison available: Fitzjames writes the word “April” again later in the same line.]

Aside from the missing handwriting, Cheyne’s VPR photograph also shows that the foxing/staining has increased since the document’s recovery. Des Voeux’s rank of “Mate” is just shy of unreadable today, whereas in 1859 it was cleaner than Gore’s “Lieut”.

* * *

Considering this Cheyne photograph, one conclusion to draw is that there is no single “canonical” Victory Point Record image. Facsimiles like the Netherclift make for easier reading, but they are still mere facsimiles. The modern Greenwich photograph is very sharp, but illegible in places due to stains – and now we can see that it has lost some original handwriting. The Cheyne photograph restores our view of that handwriting – but the more primitive photography renders the staining opaque, in addition to creating some apparently out-of-focus areas. Finally, the document in Greenwich itself (and many facsimiles) still requires the reader to know the words missing from the lower corner in order to read it properly. Anyone studying this single record therefore requires three versions on hand to see it from every angle.

When considering these missing fragments of handwriting, it’s a blessing how intact this paper is. McClintock had written in The Voyage of the Fox that the VPR was “much damaged by rust” and that “a very few more years would have rendered [it] wholly illegible.” Mentally scissor off any quarter of the document – or delete a line of text – and imagine the contortions that would be done trying to understand, e.g., fragments of the section on “Sir James Ross’ pillar.” It’s a good practical exercise to prepare for what might be coming if only fragments of papers are recovered from Erebus and Terror.

[Note: The careful reader will notice that the word “April” is almost fully extant in the Illustrated London News facsimile – which predates at least the publishing of the Netherclift facsimile by three months. This should be disregarded. While the ILN facsimile is useful for showing the inferred words, it is otherwise quite inaccurate as compared to the original document.]

– L.Z. February 18, 2021.

Originally published as Part 4 in my series on Cheyne’s relic photography (link to Part 1 in the series).

* * *

TUESDAY / AFTER

There’s a significant gap in the first two lines of the 1848 note. This is the corner that is damaged and partially missing. Might there have been additional words where the paper is gone?

Having started writing with a particular edge margin, it is improbable that Fitzjames would follow it for two lines, then switch to a different page edge margin for the next two lines. We have to ignore the damage we currently see to the lower left corner, and imagine a clean sheet of paper when Irving/Fitzjames first broke the solder on the metal case. (And, if there were already incipient corner damage, it would be even more improbable that Fitzjames would tightly curl his edge margin to that damage.)

I suggest that “Tuesday” and “after” are the lost words. Both sentence constructions are used elsewhere in the same document by Fitzjames: “Monday 24th May 1847” and “after having ascended Wellington Channel.” The reconstructed first sentence would then read like this:

The Victorians were at least visually aware of this gap. The Illustrated London News’ facsimile (seen above; Oct 1 1859, p. 327) added in the missing letters of the half-surviving words (not all facsimiles did; see the Netherclift in McClintock’s The Voyage of the Fox). From that printing, anyone picking up the newspaper could see the blank area. Therefore it’s possible that a “Tuesday”/“after” solution was suggested long ago. I would be interested if anyone finds evidence of that – or can suggest another word choice beyond Tuesday/After.

There’s a significant gap in the first two lines of the 1848 note. This is the corner that is damaged and partially missing. Might there have been additional words where the paper is gone?

Having started writing with a particular edge margin, it is improbable that Fitzjames would follow it for two lines, then switch to a different page edge margin for the next two lines. We have to ignore the damage we currently see to the lower left corner, and imagine a clean sheet of paper when Irving/Fitzjames first broke the solder on the metal case. (And, if there were already incipient corner damage, it would be even more improbable that Fitzjames would tightly curl his edge margin to that damage.)

I suggest that “Tuesday” and “after” are the lost words. Both sentence constructions are used elsewhere in the same document by Fitzjames: “Monday 24th May 1847” and “after having ascended Wellington Channel.” The reconstructed first sentence would then read like this:

Tuesday 25th April 1848. HMShips Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April, 5 leagues NNW of this after having been beset since 12 Sept. 1846.

The Victorians were at least visually aware of this gap. The Illustrated London News’ facsimile (seen above; Oct 1 1859, p. 327) added in the missing letters of the half-surviving words (not all facsimiles did; see the Netherclift in McClintock’s The Voyage of the Fox). From that printing, anyone picking up the newspaper could see the blank area. Therefore it’s possible that a “Tuesday”/“after” solution was suggested long ago. I would be interested if anyone finds evidence of that – or can suggest another word choice beyond Tuesday/After.

[I have come across one alternate suggestion, such as it is. Gilder’s book on Schwatka’s search reported that McClintock’s VPR transcript left at Victory Point put the word “The” before “25th April.” However, merely the word “The” would not be enough to fill the blank area. Further, if the word “The” had been extant at the time, the word beneath it ought to have been at least somewhat extant – yet no word is added. I think this “The” suggestion can be dismissed. The Gilder/Schwatka transcript contains a very high number of errors/deviations compared to the original note; while it’s hard to say who created the errors, Schwatka or McClintock, it’s notable that there are far fewer in the Shingleton transcript (link to Visions of the North) written aboard the Fox.]

– L.Z. February 25, 2019.

Originally published at RtFE (link to private group).

Updated January 1, 2021. Note about the Gilder/Schwatka suggestion of “The” added.

* * *

FINGERPRINT

Alison Freebairn arranged for me to be able to photograph the Victory Point Record in London on February 5th, 2020. Blowing up my photos, I can see a fingerprint at the bottom of the note.

With the naked eye, it is difficult to see unless you know where to look and the light catches it. Even in my macro photos, it is just barely surviving. I’ve written the museum alerting them to the print.

It is incomplete. Unless some other type of examination revealed substantially more, there’s not enough here to get a full print.

It exhibits both the curved swirl area of a fingertip and – separated by a ridge in the paper – the horizontal lines nearer the knuckle. Given this orientation, the finger then goes off the bottom of the page diagonally.

I count 5 distinct lines in the horizontal bands, and at least 12 distinct lines in the circular-pattern area.

Notably, the fingerprint is in a blank area with no writing or printing.

I see nothing else resembling it, in color or pattern, anywhere else on the note. (Excepting the back of the note, which I cannot examine as the note is secured down.)

I had nothing to measure it, but I would estimate that from the top of the curved lines to the horizontal lines is about 1.5 inches. The size looked roughly reasonable, but that’s all the more I can say.

The color of the fingerprint is a very faint black/gray. When I separate the photograph’s colors by warmth, the fingerprint’s color temperature is as cool as the printed Admiralty text. It is not the handwritten ink color, and it is not the water/rust stains color; they are much warmer in tone.

A fingerprint could be anyone from the original expedition through to modern researchers.

However, knowing where to look, I can see that this print is still there in the museum’s photo that is available online. That pre-dates the Death In The Ice tour at least. Given that the 2015 Erebus documentary showed the VPR encased in glass, it should also pre-date that glass case. As a general guide, the last time anyone would have dared press a dirty thumb on the VPR is quite a long time ago.

Notably also, it is alone and unsmudged at the bottom of the note. Based on the more severe water damage, this was the outermost rolled edge of the paper when the VPR was rolled up in its case. This fingerprint therefore might have been the anchor point for someone unrolling the note on a flat surface.

– L.Z. February 8, 2020.

UNDERLINED ALL WELL

* * *

FINGERPRINT

With the naked eye, it is difficult to see unless you know where to look and the light catches it. Even in my macro photos, it is just barely surviving. I’ve written the museum alerting them to the print.

It is incomplete. Unless some other type of examination revealed substantially more, there’s not enough here to get a full print.

It exhibits both the curved swirl area of a fingertip and – separated by a ridge in the paper – the horizontal lines nearer the knuckle. Given this orientation, the finger then goes off the bottom of the page diagonally.

I count 5 distinct lines in the horizontal bands, and at least 12 distinct lines in the circular-pattern area.

Notably, the fingerprint is in a blank area with no writing or printing.

I see nothing else resembling it, in color or pattern, anywhere else on the note. (Excepting the back of the note, which I cannot examine as the note is secured down.)

I had nothing to measure it, but I would estimate that from the top of the curved lines to the horizontal lines is about 1.5 inches. The size looked roughly reasonable, but that’s all the more I can say.

The color of the fingerprint is a very faint black/gray. When I separate the photograph’s colors by warmth, the fingerprint’s color temperature is as cool as the printed Admiralty text. It is not the handwritten ink color, and it is not the water/rust stains color; they are much warmer in tone.

A fingerprint could be anyone from the original expedition through to modern researchers.

However, knowing where to look, I can see that this print is still there in the museum’s photo that is available online. That pre-dates the Death In The Ice tour at least. Given that the 2015 Erebus documentary showed the VPR encased in glass, it should also pre-date that glass case. As a general guide, the last time anyone would have dared press a dirty thumb on the VPR is quite a long time ago.

Notably also, it is alone and unsmudged at the bottom of the note. Based on the more severe water damage, this was the outermost rolled edge of the paper when the VPR was rolled up in its case. This fingerprint therefore might have been the anchor point for someone unrolling the note on a flat surface.

– L.Z. February 8, 2020.

* * *

{ Tasmanian Archives: Jack Thwaites Collection; NS1155/1/20. }

“…the words ‘All well’ were not underlined.”

– Cyriax on the Gore Point Record (“The Two Franklin Expedition Records,” The Mariner’s Mirror, 1958).

I believe this remark by Cyriax was an error, causing an unnecessary amount of speculation on why the VPR’s All Well is underlined while the GPR’s is not. Zooming in on the publicly available image of the Gore Point Record, I can see a faint underline there. It is very faint – but it is faint just like the letter “p” in “Expedition” above it. The ink seems to have run out on the last letter “L” of “well”, just before Fitzjames drew the underline stroke.

Now that Regina Koellner has located the ‘3rd Note’ or Disko Bay Record (link), we can see that this All Well did not have a Fitzjames underline. On the other hand, this All Well is (unlike the other two) already sitting on a printed line, being several lines higher on the Admiralty form.

Since writing this, I have been able to examine a more recent and much higher resolution image of the Gore Point Record (December 2019). Again I observed a faint underline beneath the GPR’s All Well.

– L.Z. February 13, 2019.

– L.Z. February 13, 2019.

Originally published at RtFE (link to private group).

* * *

{ Ice World Adventures, 1876. }

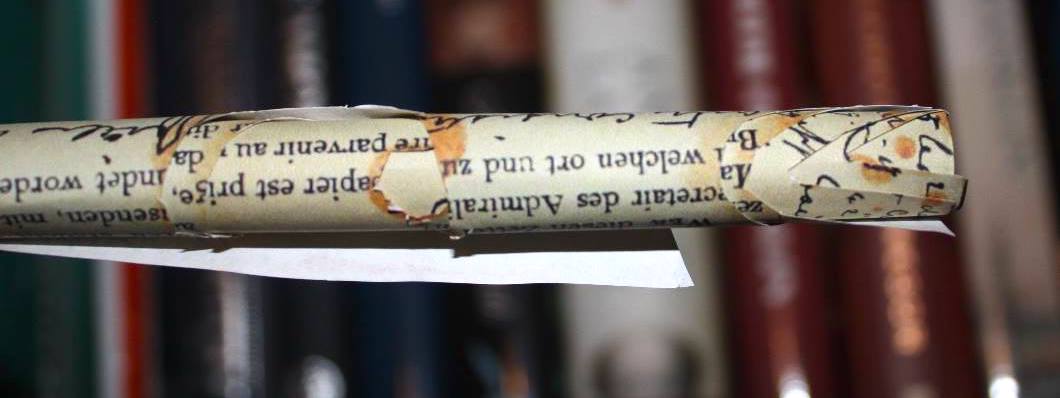

{ Two Franklin Expedition cylinders at Greenwich. }

For some time, the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich considered AAA2229 to be the cylinder that had held the Victory Point Record. Recently that was changed to AAA2344. Their website notes that when the VPR is rolled up in such a way as to align its rust stains (a clever trick I saw Regina Koellner do in November 2014), then the diameter of the rolled paper matches the diameter of cylinder AAA2344.

{ Regina Koellner's VPR rolled to align the (cut out) water/rust stains. }

I am not sure why AAA2229 was previously considered the VPR’s cylinder, or how far back into the past that attribution goes. However, I think it is possible that both answers are correct: the smaller cylinder may simply have been inside the larger one. The sizes seem to allow for this, and it would explain why Greenwich originally thought AAA2229 was the correct cylinder.

One reason to use both cylinders is to protect from the outside a watertight balloon or bladder that may have covered the inner cylinder. I’m aware of no evidence for this having been done with the VPR. However there is evidence of it from just a few years later: when Mecham found the Investigator’s note in a copper cylinder, he said, “I drew out a roll folded in a bladder” (12 October 1852).

{ Illustrated London News, 15 Oct 1859 p. 363. }

It is possible that just such a Victory Point Record bladder is what is shown in the Illustrated London News relics sketch on October 15, 1859 (the open tube above cylinder AAA2344). Granted, that tube may merely be the cylinder that held the Gore Point Record. But the Gore Point cylinder is on display at SPRI in Cambridge today (Y:54/20/2), and shows none of the damage to one end visible on the mystery tube in the 1859 ILN sketch.

{ Cylinder at SPRI (Y:54/20/2). Author photograph. }

There is another possibility: that the larger AAA2229 was put over AAA2344 by James Fitzjames. In order to add the 2nd (1848) note to the VPR, he had to break open the soldering on cylinder AAA2344. Adding cylinder AAA2229 over it may have been his way of compensating for that break.

{ Cylinder AAA2344, photographed by the author. }

I take no position on any of these cylinder ideas. They are all possibilities, but I see no way to prove or disprove them.

– L.Z. Mostly originally argued August 22nd, 2018, at RtFE (link).

– Possible bladder sketch noted October 8th, 2020 (link).

– Possibility that AAA2229 was added by Fitzjames (to compensate for breaking the solder) added October 12th, 2020.

* * *

All words in parenthesis are the standard suppositions regarding the missing lower left corner. The opening date “25 April” is assumed given that Crozier’s handwritten line states, “start on tomorrow 26th.”

For simplicity I have typed Fitzjames’ ordinal number suffixes (22nd, 11th, etc) as normal text, whereas in the document he wrote them as superscript and put a dot underneath them.

I am omitting three characters (a caret and two curly braces) used by Fitzjames to insert text from one line into another. Those three characters appear in the original document at the following points.

1st note: {Wintered2nd note, right margin: 1831‸2nd note, upper margin: HMS}

[The 2nd/1848 note, around the margins:]

[Left margin:]

(25th April) 1848 HMShips Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April, 5 leagues NNW of this

(having) been beset since 12th Sept 1846. The Officers & Crews consisting of 105 souls under the command

(of Captain) FRM Crozier landed here in Lat 69º.37’.42” Long 98º.41’

(This) paper was found by Lt. Irving under the Cairn supposed to have

[Right margin:]

been built by Sir James Ross in 1831 4 miles to the Northward – where it had been deposited

by the late Commander Gore in May June 1847. Sir James Ross’ pillar has not

however been found and the paper has been transferred to this position which

is that in which Sir J. Ross’ pillar was erected – Sir John Franklin died on the 11th June 1847 and the total loss

[Upper margin:]

by deaths in the Expedition has been to this date 9 officers & 15 men.

James Fitzjames Captain HMS Erebus

FRM Crozier

Captain + Senior Offr

and start on tomorrow 26th

for Backs Fish River

[The 1st/1847 note:]

H. M. S.hips Erebus and Terror

28 of May 1847

Wintered in the Ice in

Lat. 70º.5’ N Long. 98º.23’ W

Having wintered in 1846–7 at Beechey Island

in Lat 74º.43’.28” N. Long 91º.39’.15” W After having

ascended Wellington Channel to Lat 77º._ and returned

by the West side of Cornwallis Island.

Sir John Franklin commanding the Expedition

All Well

Party consisting of 2 Officers and 6 Men

left the ships on Monday 24th May 1847

GM Gore Lieut

Chas F Des Voeux Mate

[The pre-printed Admiralty message:]

WHOEVER finds this paper is requested to forward it to the Secretary of

the Admiralty, London, with a note of the time and place at which it was

found : or, if more convenient, to deliver it for that purpose to the British

Consul at the nearest Port.

[Repeated (with some variation, e.g. “Gravenhage”) in:

French

Spanish

Dutch

Danish

German]

– L.Z. 2018–22.