Written by Logan Zachary, researched with Alison Freebairn.

October 1, 2021.

Thank yous:

Elizabeth Cheyne

Mary and Steve Williamson

Shaun Williams

Kenn Harper

{ John Powles Cheyne's Fox photograph. Courtesy Kenn Harper. }

{ Fox photograph held by Mary Williamson. LA/19/18. }

The previous article in this series looked into Where The Fox Docked (link) on her return to London in 1859, by comparing two historic photographs of McClintock’s search ship.

I had written that no other photograph may exist of these individuals. Which was a lie: someone appears in both Fox photographs.

A big beret cocked at an angle. A beard without moustache. A white coat. A face like the Victorian Stan Rogers. This unnamed man in the Fox photograph held by Mary Williamson is a dead-ringer for one of the men in Cheyne’s Fox stereograph.

I don’t know who this is. Maybe it's Parker Snow, the eccentric Franklin searcher with a knack for turning up in odd places. But the likeliest answer must be that he is one of the Fox’s crew. I’d like to think it’s Richard Shingleton, the Officers’ Steward who had written out his own transcript of the Victory Point Record.

But there the question must remain. This article will be a speculative piece looking into who was photographed with the Fox after she returned from finding the Victory Point Record. Further work may uncover these identities, but, it’s just as likely that we’ll never know.

THE MAN IN THE BOWLER HAT

The 2nd article in this series, Cheyne’s Motion Pictures, showed that two versions of Cheyne’s Fox stereograph exist. The more common photo features a man in a black suit (below, right), while the more rare alternate shows two additional men dressed in lighter clothing (below, left).

{ Cheyne's Fox stereograph, alternate versions. }

The most interesting detail among the men is that the black-suited man in each photograph is not, in fact, the same man (side-by-side comparison below).

The lone black-suited man wears a top hat and a large black beard. But the black-suited man in the troika has no beard, may be fair-haired, and is wearing what looks like a bowler hat.

When I saw this, I came to believe that the man in the bowler hat may be the photographer, John Powles Cheyne. To explain this, I need to describe a photography principle that doesn’t have a name, but will be familiar to anyone alive in the pre-selfie era.

Imagine you and your friends are chartering a plane to visit Beechey Island. Eschewing modernity, you leave all electronics behind and land with only a vintage daguerreotype camera.

Only you know how to operate this camera. As you prepare to photograph the graves, you suggest that your friend DJ stand by the headstones for scale. The picture is taken and seems successful. With one photo accomplished, DJ now suggests that you – as the group photographer – should stand in the 2nd photograph. You assent, and you invite everyone else to come into the frame with you, while giving DJ a crash course in taking a daguerreotype.

Every friends trip or family vacation before the iPhone era used to operate in this manner. Unless someone had a tripod and a timer, group photos were naturally bifurcated: the principal photographer was occasionally coaxed into being in a shot, while the secondary photographer went missing in those photos.

Without this effect, we have no obvious reason why someone was a subject in Cheyne’s 1st photo, but then not permitted to stand in the 2nd photo – and this despite one of the photos being a group photo.

The simplest explanation is that Cheyne is one of these four men. Either he wished to appear in his own series, or his companions coaxed him into doing so. Into our own era, this effect has held true: the photographer is the most likely person to appear in their own roll of film. Currently Cheyne is the one person we know for certain was actually at the East India Docks that day.

{ Portrait photograph courtesy Elizabeth Cheyne. }

And indeed, John Powles Cheyne bears a basic resemblance to the man in the bowler hat: a trim figure, clean-shaven or close to it, and fair or light haired. The man in the bowler hat even has the “hand high on the hip” arm pose that Cheyne used to pose for this (above) studio portrait.

[This portrait photograph of John Powles Cheyne was kindly lent for this article by his great-granddaughter, Elizabeth Cheyne of Whitby. She was able to confirm for me that the family name's pronunciation is exactly like “chain.”]

THE MAN IN THE TOP HAT

There is a problem with identifying the man in the bowler hat as John Powles Cheyne: it implies that someone else in the group was capable of operating an 1859 camera – being instructed to take a stereograph no less.

Alison Freebairn (of Finger-Post.blog) proposed a remarkably simple solution to this: the man in the top hat may be David Walker. Walker was the doctor on McClintock’s Fox expedition. More importantly, Walker was also the expedition photographer.

{ Top hat man flanked by painting and photograph of David Walker. }

Walker had dark hair and often wore a large beard. As Cheyne has a general resemblance to the man in the bowler hat, so Walker resembles the man in the top hat. As a Fox expedition member, Walker is one of the most likely persons to be present. And, as Alison pointed out, Walker had the photography experience for Cheyne to trust the doctor with operating his camera.

Our friend Shaun Williams (writer of a blog about Captain Marryat) helped push Alison’s theory further. Shaun alerted us that David Walker had done more than photography on the McClintock Expedition: he had practiced some stereography during that expedition as well.

Below: Two David Walker stereographs from the Fox Expedition, both in Bellot Strait.

{ The ‘Fox’ in winter quarters at Port Kennedy. Bellot St. April 1859. }

{ A123-013 Le Vesconte. The Rooms, St. John's, NL. }

{ A Bear on deck. taken on board the ‘Fox’ in Bellot St. Sept. 1858 }

{ A123-015 Le Vesconte. The Rooms, St. John's, NL. }

{ A123-015 Le Vesconte. The Rooms, St. John's, NL. }

Shaun had seen these Walker stereographs in the Le Vesconte family collection held in St. Johns, Newfoundland. As far as I know, the above is the only Fox photograph taken aboard her – a unique view of a ship now disintegrated on the Arctic seafloor. The distant hills in the background (moving! she was not yet iced in) are the shores of Bellot Strait. There is even a passage in Voyage of the Fox where McClintock mentions Dr. Walker photographing a polar bear on deck (more on this in Appendix 2).

Thus, Cheyne would not have been handing his stereography off to a neophyte. In David Walker, Cheyne would be able to put his camera into the hands of an experienced photographer, one who had very recent stereography experience to boot.

Both the Cheyne and Walker identifications are at this point tentative, built on fuzzy resemblances and a speculative logic chain.

However, Alison’s research has since turned up a very unusual clue supporting her hunch about David Walker: this stereograph below.

At a glance, we know what this image is: the 1859 Fox stereograph by John Powles Cheyne, slide #13 in his set.

But it is not.

This is not a Cheyne Fox stereograph. This is a new – a third – stereograph of the Fox. Alison uncovered that someone else took an 1859 stereograph of the Fox at the East India Docks’ Basin – and most interestingly, that person took their stereograph from the same vantage point as Cheyne.

And that photographer is: David Walker – the Fox expedition’s photographer, and Alison’s prime suspect for the man in the top hat in Cheyne's own stereograph.

{ Fox stereographs: Cheyne's above, Walker's below (MCL/24). }

Alison found this Fox/Basin stereograph in a collection of David Walker photographs held at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum, on loan from the McClintock family. Prior to this, we had no direct link of any kind between Cheyne and Walker. I had hoped that we might find correspondence one day. But here we have a connection I would not have imagined: they in fact both took the same stereograph of the Fox.

What is the most likely explanation for how this happened? I think Cheyne must have seen Walker's stereograph in London, and told him that he'd like to take his own, for a slides set that he was working on. It's even possible that this moment was the genesis of Cheyne's project of a stereographic series on the recent Franklin discoveries. Walker then offered to take Cheyne to Blackwall himself, and show him exactly where he stood to get that angle.

Supporting this sequence is the fact that Walker's stereograph almost certainly was taken first. Indeed, Walker likely took his stereograph on the day the Fox arrived at the Basin, for the simple reason that he would have his bulky photographic equipment already out there in Blackwall with him. As the ship’s doctor, he would also have less to do in preparing the ship for a stay in port, the free time needed to compose and capture a stereograph. A close comparison of Walker’s two sequential frames shows evidence of at least three figures moving – separately – on deck, as though this work is indeed still in progress. One of them, in a long coat near the bow in Walker’s right frame, is clearly facing the camera, as though he knows Walker is there and what he is doing. [I apologize that I can not show this level of detail here, per the National Maritime Museum's rules regarding historic photography.] The back of Walker’s stereograph is dated September; this leaves a fairly narrow window, as we know the ship didn't arrive until the 23rd of the month. There’s also a davit missing from the Fox in Walker’s shot that is present in Cheyne’s; as the Fox was being prepared to be sold in November, it’s far more likely that a missing davit would be replaced for the upcoming sale than for one present davit amongst four to have been taken away.

With Walker's stereograph coming first, and Cheyne some time later taking the same stereograph from the same angle, a likely explanation for this coincidence is that Cheyne had seen Walker’s Fox stereograph. And with the subjects in Cheyne’s two stereographs suggesting a 2nd photographer was present, that 2nd photographer is therefore highly likely to have been David Walker.

We may never know for certain. But it's remarkable that at the outset, this started with nothing more than Alison observing that the man in the top hat resembled the ship's doctor.

THE FIVE WIVES

{ Mary Williamson's Fox photograph. Langney Archive LA/19/18. }

While Mary Williamson's Fox photograph is presumably a Fox crew photo, it is not the crew that are spotlighted: it’s the wives. That is who is lined up in front and given prominence. Five in all, plus a blurred child (3rd figure from the right). By comparison, the rest of the photo’s subjects are milling around haphazardly another ten feet back.

And this fact is strangely complimented by who was named in the lower margin note.

Just arrived at Blackwall, 23rd Sept 59.

[Names left to right. – L.Z.]

William Harvey, 2nd Mate.

William Hampton, Able Seaman.

John Simmonds, Boatswain’s Mate.

Henry Toms, 2nd Mate.

George Carey, Able Seaman.

Alexander Thompson, 2nd Mate.

The writer of the margin note named only six crewmen. All (but one) of those named has a wife attached. The requirement for being named seems to be that you were part of a couple. (The odd extra is “Old Harvey,” alone on the far left.) Surely someone who could name six crewmen of the Fox expedition could name them all?

And someone else isn’t named: the wives themselves.

I have a theory to try to explain this: I think the writer of the note may have been one of the wives. And, that perhaps it is they who commissioned this photograph to be taken. These women had known that their men might never return, that they were sailing into a world of ice that had chewed up bigger ships and 129 men. They would have no one in their life to relate to over this anxiety, for years, except each other.

And afterward, when it came time to write down names to be remembered, they wrote down the names of their girlfriends’ husbands. They didn’t bother with the rest of the crew. And, after years of waiting for the return of the ship together, they did not need to be reminded of each other’s names.

Given that, they are the most unique feature of this Fox photograph. It’s rare enough to see a photo of a ship’s crew from this era, but here we are looking into the faces of their wives. Each face shows a bit of personality, and one can start to imagine how they interacted, what it was like when they sat down to talk. I would like to find their names – and, their descendants. These couples would be the ancestors of people alive today. That child too young to stand still may be someone’s great-grandparent, and this would not be their last photograph.

This is all supposition, and I can take it no further. If it is true, then why did they include Old Harvey? Had they known his significant other, who passed away while the expedition was gone? Perhaps of note, one name is seemingly written incorrectly: Robert Hampton in McClintock’s book is written on the photograph as William Hampton.

THE CREW

{ Fox personnel. An “M” if named in Mary’s Fox photo. }

Who, then, is everyone else? Is it simply the obvious answer: the Fox’s crew? I want to make an argument suggesting that it is.

If you take the Fox’s personnel list, and cross off the 3 men who died, cross off the 2 men who returned to Greenland, and cross off the 6 men already named in Mary’s photograph, that leaves 15 possible men: 10 crew and 5 officers.

Further, we can see that McClintock isn’t pictured. Nor does anyone seem to be a strong match for the other famous faces: William Hobson, Allen Young, David Walker, and Carl Petersen.

We might assume that the expedition brass are elsewhere; maybe they’d been called immediately to the Admiralty, to testify before dispersing out into the country. Whatever the reason, there’s a logic to the officers being either missing or present as a group from a crew photograph.

Subtracting those 5 officers from the list leaves us with exactly 10 men – and I count 10 unnamed faces in the background of Mary’s photograph.

{ The Ten Unknowns in Mary’s photograph. LA/19/18. }

This coincidence would suggest that the figures in the background are indeed the rest of the Fox’s crew. 10 men who were neither officers, nor Greenlanders, nor dead, nor called to stand in front with the wives.

They endured two years of isolation, winters without sunlight, malnutrition, buried three of their company, came upon the “Peglar” skeleton on the ground, and dug out two more skeletons from a boat filled with snow. We would treat half of them for trauma today.

* * *

One wonders where all these top hats came from.

A top hat is a bulky item for men in cramped quarters. Was there a room on the Fox’s lower deck devoted to holding all the top hats? I wonder if men on a voyage filled with saltwater, damp, smoke, and polar bears on deck would risk trying to keep a top hat in tip-top shape through two years of polar exploration.

Which makes one wonder if this photograph really was taken when “just arrived,” as the margin note is written. McClintock in the conclusion of Voyage of the Fox mentions the entire crew being together again on the 27th, several days after the 23rd arrival date. And Alison questioned how long it would take five wives in 1859 (some perhaps in Scotland) to be both notified and then arrive in London. Perhaps “just arrived” loosely refers to any time in the first few weeks after arrival. If the note wasn’t written until a few years later, any time in Autumn 1859 would seem like “just arrived” in retrospect.

This ambiguity is built in to this study. With the exception of the man in the beret appearing twice, no assertion in this article is conclusively true. These are attempts to establish the most likely identifications, in lieu of further information coming to light. The primary reason for doing so is negative: as the most likely solutions, they are the first that future research should try to disprove.

The End.

– L.Z. October 1, 2021.

Special thanks to Elizabeth Cheyne of Whitby, great-granddaughter of John Powles Cheyne, for her assistance with this article. Elizabeth is pictured here with an Arctic scene painted by her great-grandfather.

* * *

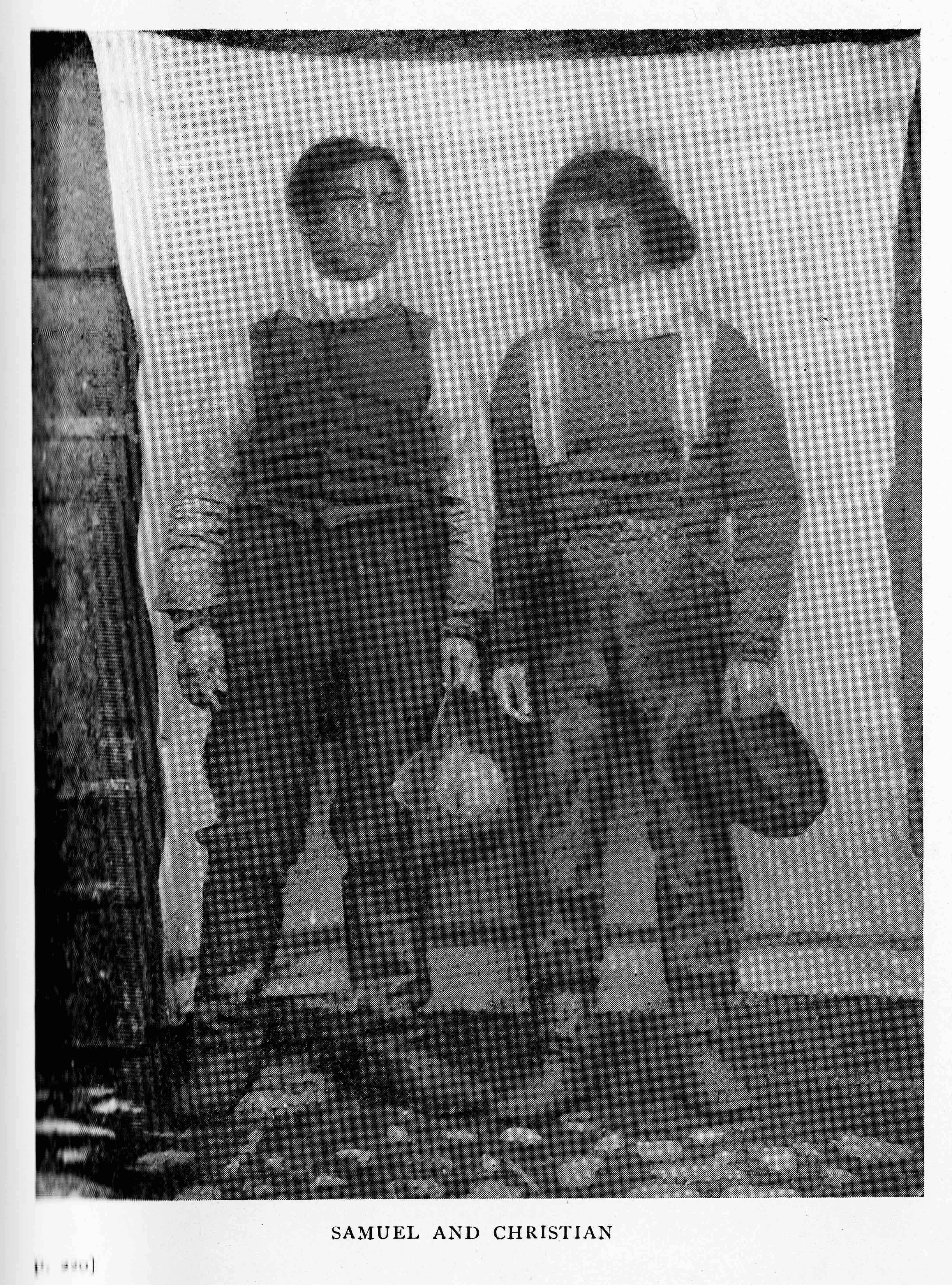

Appendix 1: The Two Greenlanders.

{ The two Greenlanders, from Life of McClintock by Markham. }

{ Image courtesy Alison Freebairn. }

In Clements Markham’s 1909 biography of McClintock, he has this remarkable photograph of Anton Christian and Samuel Emanuel: the two Greenlanders who went on the Fox Expedition.

Christian was present for most of the major revelations regarding the missing Franklin Expedition. He accompanied Hobson’s sledge party, and so would have seen the Victory Point Record first unrolled, and would have helped uncover the skeletons at the Boat Place. Samuel, meanwhile, was part of Allen Young’s search and mapping expedition of Prince of Wales Island.

I do not know who took this photograph, or when. I also do not know where Markham located the original. If anyone knows more about this photograph, please contact me. While Markham’s caption of “Samuel and Christian” seems like a mixing of a first name and a surname, it should be noted that those are the abbreviated names with which McClintock’s book refers to them. On a minor note, Christian introduces himself as a 23 year old orphan when he signs on near Disko Island, but twice later in the book he references his mother – a contradiction which Leopold’s narrative doesn’t spot.

Assuming Mary’s Fox/Wives photograph is indeed the Fox’s full crew, then with this photograph of the two Greenland Inuit, it means that the only person who survived the Fox Expedition that we do not have a photograph of is, oddly enough, Lt. Hobson – the leader of Christian’s sledge party that discovered the Victory Point Record. That Hobson’s face alone, “the man who found the record,” should be lost to photographic history is a truly bizarre twist of fate. [For an Illustrated London News sketch of him – drawn from a now-lost photograph – see the previous article in this series, Where The Fox Docked (link).]

Appendix 2: David Walker’s Polar Bear on the Fox stereograph.

{ A123-015 Le Vesconte. The Rooms, St. John's, NL. }

{ The Illustrated London News, October 29, 1859. }

David Walker's stereograph of a polar bear on the Fox may ring a distant bell to Franklin researchers. A sketch of it appeared, uncredited, in The Illustrated London News – next to a sketch of John Franklin's birthplace in Spilsby (itself surviving today much as it appears in this sketch). The newspaper added four sailors onto the Fox's deck, but otherwise the sketch is remarkably faithful to the original.

In the left-right movement of the GIF animation, we see the horizon moving – or rather, we see the Fox and Walker's camera are moving relative to the distant shore. This shows us that, on the date this stereograph was taken, the Fox was still moving. She was not yet iced in. So when was this stereograph taken?

In The Voyage of the Fox, McClintock actually mentions this event, that Walker photographed a polar bear on deck in Bellot Strait (21 Aug 1858): “Many seals have been seen; a young bear was shot, and Walker took a photograph of him as he lay upon our deck, the dogs creeping near to lick up the blood.” If there's the blur of a dog in these images, I can't see it. On the stereograph, a caption underneath reads: “A Bear on Deck, taken on board the ‘Fox’ in Bellot St. Sept. 1858.” These sources agree on the location of Bellot Strait, but disagree on the month: August vs. September. As no polar bear seems to have been shot by the expedition during September 1858, I would trust McClintock's diary narrative over the stereograph caption. We should therefore date the Walker stereograph to August 21st, 1858. [Nor is it the year that's possibly wrong on the stereograph, 1858 vs. 1859: the Fox had escaped from Bellot Strait by August of 1859.]

Note that this bear is not the same McClintock polar bear now on display at the Natural History museum in Dublin. That polar bear is from the big 1850-51 Franklin search.

Appendix 3: On the Walker Fox stereograph.

Something small is hanging from the front set of port davits in Cheyne's Fox stereograph – the same set of davits of which one is missing in Walker's Fox stereograph. I don't know what this is. It's not impossible that it's the kayak mentioned in news reports (see previous article in this series): “A beautiful Esquimax [sic] canoe is lashed on her larboard quarter.” I think this is unlikely, as hanging from davits does not imply “lashed,” and because I'm not certain that a kayak would survive a serious storm hanging from davits. Nonetheless I want to mention this as a possibility.

Appendix 4: Richard Shingleton's Victory Point Record transcript.

At the beginning of this article I mentioned Richard Shingleton, the Officers’ Steward on the Fox who wrote his own transcript of the Victory Point Record. For more information, Russell Potter has written an article at Visions of the North (link).

* * *

This is Part 6 in a series revolving around Cheyne’s relic photography.

- Part 1: The Missing Toy Sledge from Erebus

- Part 2: Cheyne's Motion Pictures

- Part 3: Cheyne's Relics

- Part 4: Lost Letters of the Victory Point Record

- Part 5: Where The Fox Docked

- Part 6: Who Was Photographed With The Fox?

- Part 7: Reversing the Chronometers at the Boat Place

- Part 8: A Stained London Pocketwatch

- Part 9: (forthcoming)

– L.Z. October 1, 2021.