Written by Logan Zachary, researched with Alison Freebairn.

August 4th, 2021.

Thank yous:

Mary and Steve Williamson

Shaun Williams

Kenn Harper

* * *

“…she [the Fox] looks unusually smart and gay, and our impatience to exhibit her, and ourselves at home is much increased.”– Capt. McClintock writing from the Northwest Passage (The Voyage of the Fox, 1859).

CHEYNE’S FOX STEREOGRAPH

{ The Fox in stereoview – home and triumphant. But where? }

In 1845, two Royal Navy ships departed from the Thames, sailed in search of the Northwest Passage, and vanished. Dozens of searches and fourteen years later, this lone ship – the Fox – returned to the Thames, having found a record of that lost 1845 expedition.

We know exactly where the 1845 expedition’s story began: Erebus and Terror docked at a pub on the Thames, just downstream from London in Greenhithe. You can still get a beer or dock your vessel there today. Visiting that Thames pub (now named for the 1845 expedition commander, Sir John Franklin) is a pilgrimage made by Franklin searchers today.

But the closing of the British search – the return of the Fox in 1859, the first ship to have investigated the scene of the disaster – is not a known location, and so is not visited on Franklin history tours of London.

{ Cheyne's Fox stereograph, at higher resolution. }

Yet we seem to have a photograph of the location right here. We can see a wall, two buildings, and a smokestack. Is it London though? What if it’s Portsmouth, where the Fox landed first?

We do know who the photographer was. This photograph was included in a photo series on the Fox’s newly-discovered Franklin relics, done in stereography (hence the twinned photos above). The series was photographed and sold by John Powles Cheyne, a veteran of three Franklin searches.

Where then did Cheyne take his Fox photograph?

{ Cheyne's booklet. }

In the descriptive booklet included with his set, Cheyne reveals no details (other than classifying the Fox as a “yacht”). He gives no hint about where he visited the Fox, or the date he took his photographs.

MARY'S FOX PHOTOGRAPH

However, I’ve found that we can learn more by comparing Cheyne’s photograph to another Fox photograph: one held by Franklin descendant Mary Williamson.

{ Photograph held by Mary Williamson. Langney Archive LA/19/18. }

Like Cheyne’s, Mary’s photograph shows Victorians standing next to the Fox after her return from the Northwest Passage. But with this photograph, we know the location, the date, and some of the faces. Those details were written by hand in a note scrawled along the bottom margin:

Just arrived at Blackwall, 23rd Sept 59.

William Harvey, 2nd Mate.

William Hampton, Able Seaman.

John Simmonds, Boatswain’s Mate.

Henry Toms, 2nd Mate.

George Carey, Able Seaman.

Alexander Thompson, 2nd Mate.

Before tackling that critical top line, it's worth considering who is named here.

“Old Harvey,” who told Arctic yarns to young midshipmen, and led a dance on Greenland with his flute. Hampton, who went snowblind near Montreal Island, and thus took over McClintock’s dog team. Alexander Thompson, who'd been on McClintock's 3-man spring reconnaissance journey – the first to hear the Inuit tell how Terror had sunk.

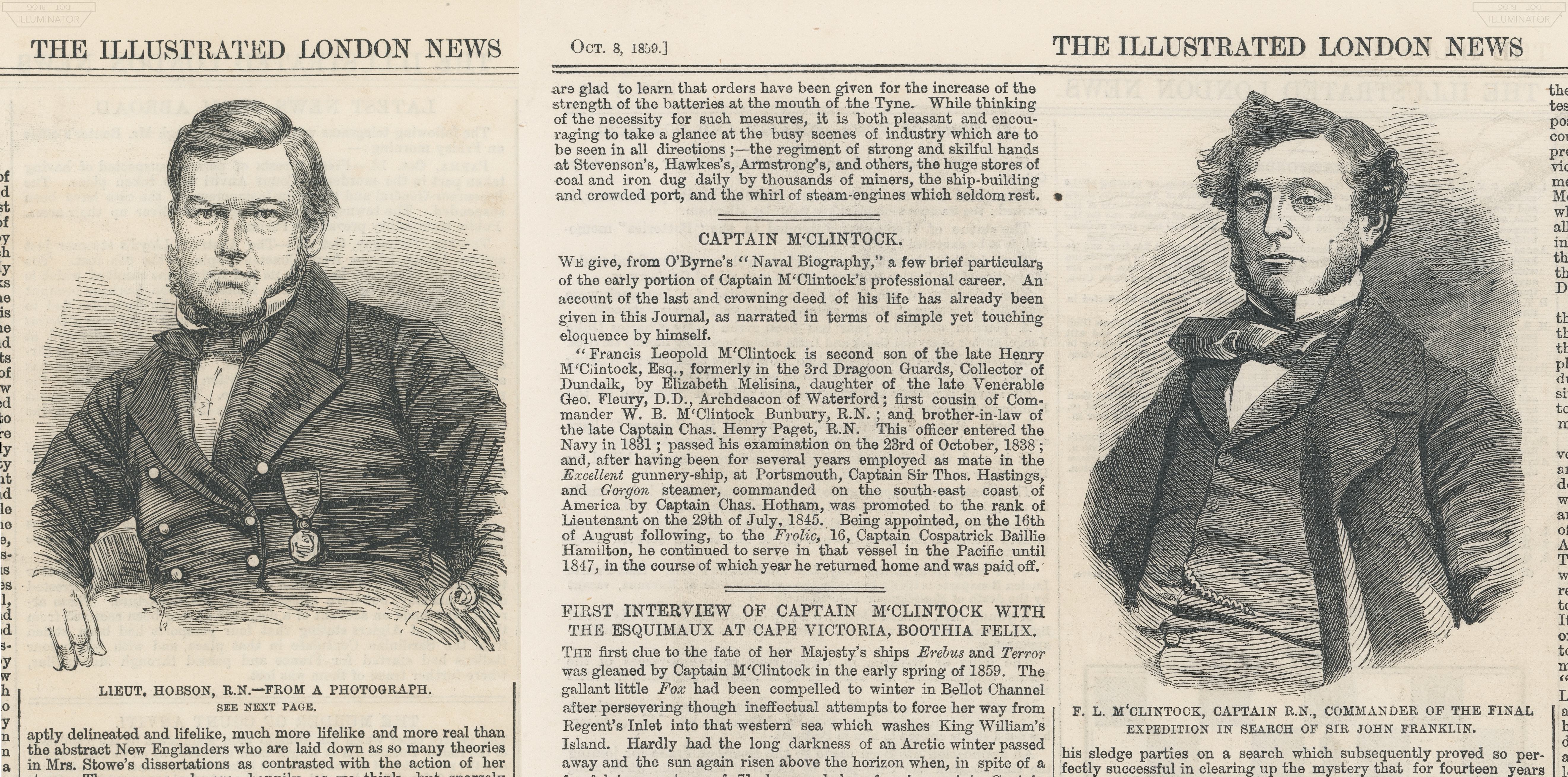

{ Hobson and McClintock in the newspapers. }

{ ILN 1859 Oct 8/15. Author images. }

The Fox’s captain, Francis Leopold McClintock, is not in Mary's photograph. Nor is Lieut. William R. Hobson, the discoverer of the Victory Point Record. The men pictured and named in Mary’s photograph are not the most famous men who sailed on the Fox. McClintock and Hobson would see their faces appear sketched in the pages of the Illustrated London News. Not these men: Mary's photograph shows faces of Victorians for whom no other photograph may exist.

Yet whoever wrote the note knew who they were.

The ability to identify those faces gives the note’s writer a good deal of credibility. No one alive today could name these men – and very few even at the time. The writer must have been alive in 1859, intimately involved with the Fox and her crew.

We can therefore trust the writer on the further details they give us: that Mary's photograph was taken at Blackwall, on September 23rd, 1859 – on the occasion of the Fox’s arrival. We are seeing the exact location on the Thames where the Fox returned to.

{ Harvey? Hampton? Thompson? The Fox's crew in newspapers. }

{ Illustrated Times, 1859 Oct 15. Author image (link). }

Knowing that location, a closer examination tells us where Cheyne’s photograph was taken.

On the edge of both photographs, we can see a bit of the next ship moored in front of the Fox.

Here they are lined up back-to-back:

The details are identical – not just the ship's lines, but also the small port/starboard stern cable apertures (open in Mary's photo, closed in Cheyne's). It is the same ship.

In addition, the same long building with peaked towers and double chimneys seen in Cheyne’s photograph is discernible in the upper left of Mary’s photograph.

Cheyne’s and Mary’s Fox photographs must be two different perspectives on the same location. In one direction, Cheyne’s photograph shows us a brick perimeter wall at water’s edge; from the other direction, Mary’s photograph shows the water’s edge curving around a short distance off.

We have two angles on the exact spot the Fox returned to. And the note writer on Mary’s photograph names the locale: Blackwall.

BLACKWALL

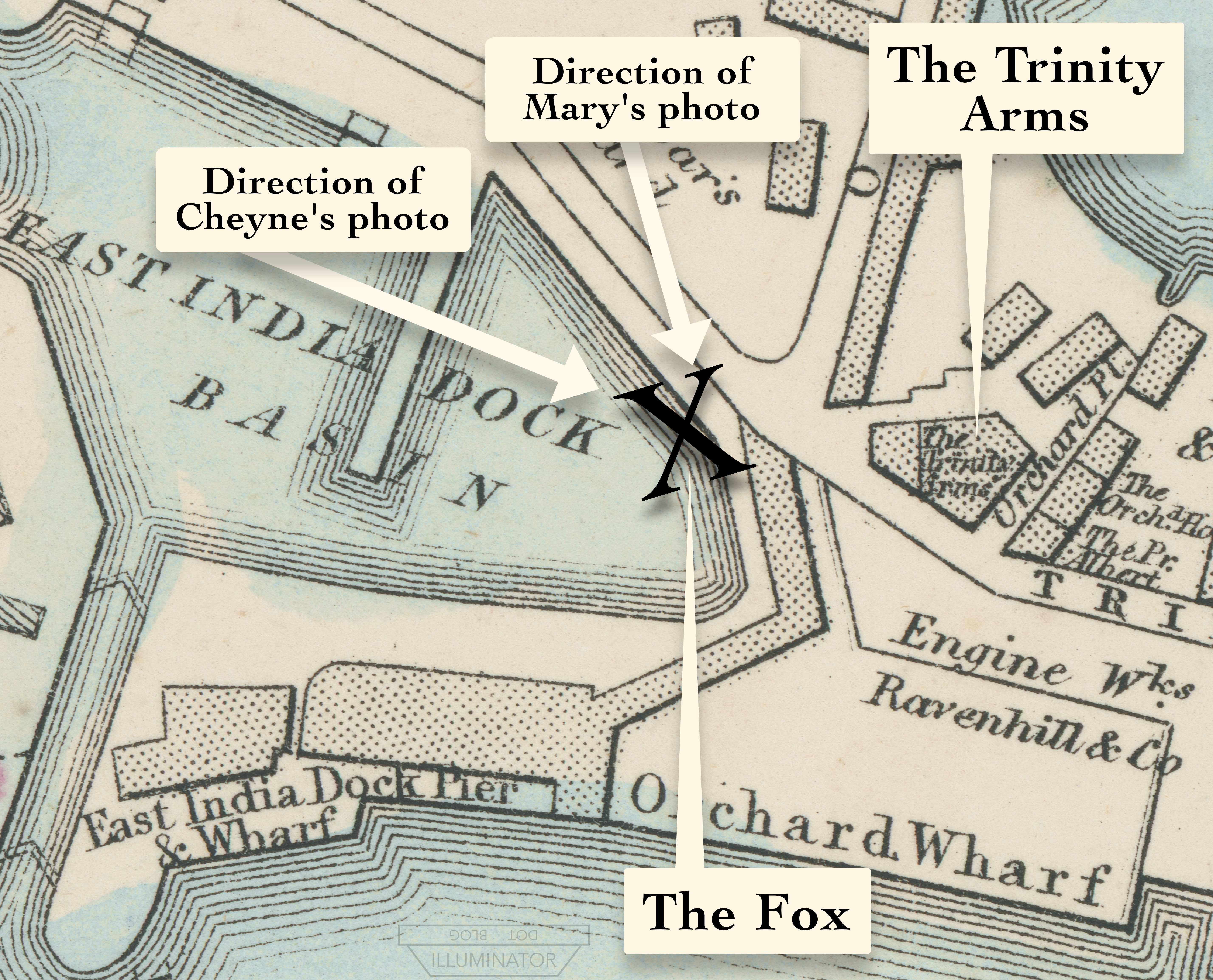

Blackwall is an East London neighborhood on the northern bank of the Thames. If you’ve visited Wren's Hospital in Greenwich, you can see Blackwall in the distance, across and down the river (to your right), at the next turn in the Thames. From the photos, all the further we can see is ship masts in the distance in Mary's photograph, but buildings and a smokestack in Cheyne's. Mary's photo must point towards water, whilst Cheyne's points towards land, somewhere in Blackwall.

The note naming Blackwall under Mary’s photograph agrees with a comment McClintock made at the conclusion of his search book, The Voyage of the Fox:

On the 23rd September the 'Fox' was taken into dock at Blackwall.

Having no nautical background, I didn’t think long on this phrase “taken into dock.” But at the conclusion of a speech at the Royal Geographical Society (14 Nov 1859), McClintock phrased that line with a little more detail:

“…on the 23rd the dock gates at Blackwall closed behind the Fox.”

The dock gates closed. So the ship didn’t merely dock at the Thames riverside somewhere, as Erebus and Terror had done at Greenhithe’s pub. The Fox docked inside a pool on the Thames, behind closed gates.

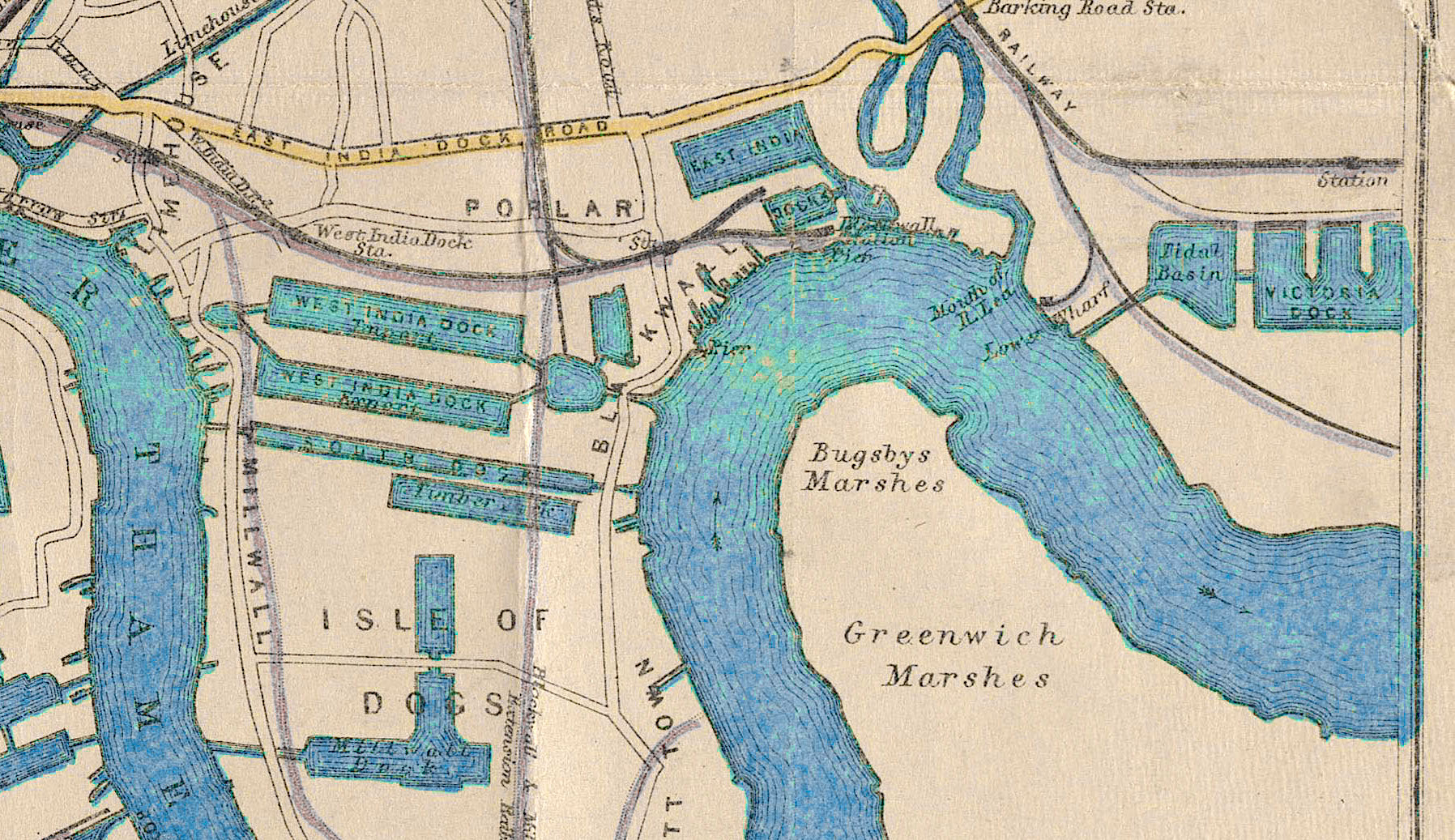

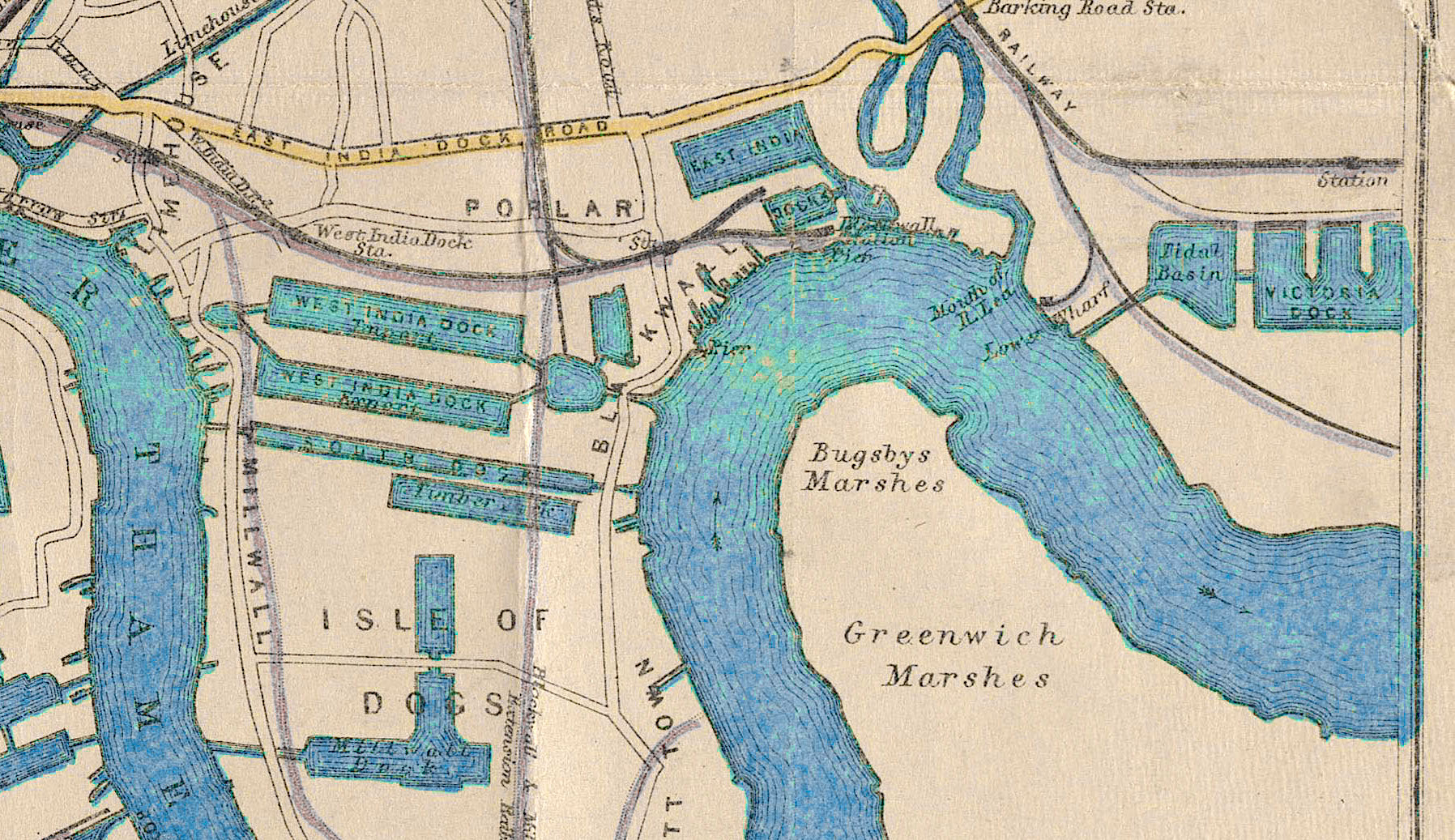

When I mentioned this to Alison Freebairn, she dug up a map showing the historic docks in the Blackwall area.

Blackwall is marked roughly in the center of this map. In addition to the obvious large rectangular dock pools, there are quite a number of smaller ones cut into the Thames’ northern bank. We squinted and took some guesses, but saw no way to narrow this down. [One nagging issue unresolved til the very end: if these docks are almost all rectangular, why does the quay in Cheyne's and Mary's photos look to be curved?]

Working on other projects, I eventually ran across this line in an 1859 newspaper article:

“On Friday week, the little screw yacht Fox, now famous, arrived in the East India Docks.”

There – the specific name of the Fox's dock: The East India Docks.

{ Ordnance Survey 1862-73 (link) }

The East India Docks in Blackwall are where Shackleton’s Endurance sailed from and where Scott’s Discovery returned to. The docks comprise a big “Imports” pool on the north and a smaller “Exports” pool to the south, connected to the Thames via a small entrance basin.

Somewhere in those pools is where the Fox was photographed on her return.

And what do they look like today?

They’re gone. Drained and built over with offices, apartments, and a hotel. The ‘Export pool’ was even briefly underneath a massive power station on the scale of Battersea. A memory of the spices that once arrived at the ‘Imports pool’ survives in the street names built on its grave: Oregano Drive, Nutmeg Lane, Saffron Avenue, etc. Clove Crescent.

That appeared to be the end of this search for the Fox’s historic Thames dock. No history field trip need linger long in an office park. Perhaps as a nod to what was lost, there's a little office park pool in the office park, over what would have been a fraction of the Imports pool. Nothing worth dignifying with a visit.

[The careful map reader will here object that I am overlooking that one East India Docks pool seems to still be there. Indeed I had overlooked it at this stage. It'll come back up shortly.]

Then Alison sent me a photo showing that some of the East India Docks’ brick perimeter walls had survived the modernization.

{ Cheyne's photo vs. East India Docks walls today. }

The brick walls in Cheyne's Fox photograph are very distinct; one can count the bricks. We thought that – though the Import/Export pools are gone – perhaps we might find the exact section of wall seen in Cheyne’s photograph. The primary question being: Which pool did the Fox dock in, Imports or Exports?

THE WALLS – THE SOLUTION

But zeroing in on those walls, two new problems popped up. And these two problems ended up solving the entire question.

Problem #1: The surviving historic walls are not an exact physical match for the walls seen in Cheyne’s Fox photograph (the vertical brickwork, similar at a glance, has differences). How could that be? Were these somehow the wrong docks?

And, Problem #2: The wall in Cheyne’s photograph is too close to the water's edge. The Victorian in the top hat would be standing on the modern sidewalk in the above photos – and that turns out to be a problem.

To visualize the walls/water problem, observe this 1841 East India Docks map:

{ The East India Docks walls. Graham 1841 (source) }

This map shows the perimeter walls (highlighted) that circuited around the East India Docks. Notice all the dark buildings encircled by the walls: warehouses, sheds, offices. There are rows of buildings – sometimes more than one row – in between the perimeter wall and the water’s edge.

We can visualize that ample amount of room a year later in this 1842 sketch, which shows the scene from the ground level.

{ Knight 1842. Author image. }

This is the northern edge of the big Imports pool, facing west. The distinctive arched building in the far corner was the main land entrance to the East India Docks (labeled "Entrance/Offices" on the 1841 map, top left corner). Notice how much room is here – especially as compared to the width of the ships. There's enough room to comfortably unload a cargo hold full of spices.

But compare that expansive area for unloading with what we saw in Cheyne's Fox photograph.

{ Tasmanian Archives: Jack Thwaites Collection; NS1155/1/20 }

The Victorian standing in Cheyne’s photograph could turn around and touch the brick wall behind him in just a few steps. And there are no loading door openings: it’s a blank brick wall. It doesn’t look like this quay was designed for loading or unloading much of anything. One couldn’t squeeze an entire warehouse in there; it’s a mere walkway. How can this be?

But there are two exceptions, noticeable on the map, where the dockyard walls do approach the water’s edge.

One is the southwestern corner of the Exports pool. But there the pool’s edge is the more definite corner of a rectangle – not the gradual curves we saw in Cheyne's and Mary’s photographs.

{ Graham 1841 (source) }

The one other place, then, where the water’s edge approaches near the dockyard wall, is at neither the Import nor the Export pool. It’s outside them – on the far eastern edge of the entrance pool, connecting them to the Thames. That entrance pool is called the ‘Basin.’

Wondering if this pool I'd overlooked could be the solution, I typed “Fox Basin” as a search term. Up popped the same “little screw yacht” newspaper article I’d found naming the East India Docks – but this version was different, adding one additional sentence:

“The little screw yacht Fox, now famous, arrived in the East India Docks on Friday. She lay alongside the quay within the basin all day.”

Italics mine: “…within the basin.” So the Fox wasn’t photographed in the Import or Export pools. She was outside them, docked in the entrance pool that connects them to the Thames. The Fox was in the Basin.

Knowing this, additional details in the Cheyne photograph come into focus. That 1841 map shows only a handful of breaks (entrances) in the perimeter walls; it shows that one is right on that easternmost edge of the Basin. If this is indeed the spot in the East India Docks where the Fox was moored, we ought to see that break.

{ Graham 1841 (source) }

{ Tasmanian Archives: Jack Thwaites Collection; NS1155/1/20 }

And there one is. If you look over the Fox's gunwales, immediately to the left of her smokestack, there is a break in the walls. (The lower blank area is possibly a white wooden wall – but above that, there is a distinct open gap.) To the immediate left of the break in the wall, we see the white top of a very small peaked roof, barely taller than the Victorian – like a sentry box controlling an entrance.

Further, the left wall is visibly lower than the right wall at the break point. And their top edges (marked green & yellow) follow perspective lines that suggest they are flexing out to the break – as we'd expect from the 1841 map. Also their construction styles are different: the left wall has extra vertical brickwork every 10-15 feet (marked in orange lines), whereas the right wall's face is flat and unadorned.

[These details also explain why the surviving Import/Export perimeter walls didn’t match the walls in Cheyne’s photograph. The Basin pool has changed shape several times, necessitating different wall constructions – such as the unmatched pair we see.]

Most important is the fact I overlooked earlier: that unlike the erased Import and Export pools, the Basin pool was never filled in. The Fox's Basin is still there.

{ The Basin. Apple Maps 2021. }

Alison Freebairn visited the Basin to investigate the scene on the ground. The Basin appears to have been rehabilitated as something of a birdwatching/nature walk area, with a wetlands on one edge, and locked up at night. Ring buoys are at intervals along the water in case James Fitzjames isn't there to save you from drowning.

The current water channel to the Thames – though Victorian – is a later 1870s construction. Amazingly, however, the notches of all the old dock channels are still visible: Imports, Exports, and the original channel that the Fox would have entered by.

{ The Basin. Photograph by Alison Freebairn. }

{ The Basin. Photograph by Alison Freebairn. }

Finally, here is the eastern edge of the East India Docks' Basin. This is where the Fox docked when she returned to the Thames – roughly where the sunlight is hitting in the distance. The brick perimeter walls are gone, and the quay's slight curve has been straightened, but the Basin and its eastern quay are still there. On this water, John Powles Cheyne stood up on another ship and photographed the Fox for his relics stereographs set. And on the walk along the water's edge, the Fox's crew – Old Harvey, Hampton, Alex Thompson – stood together for Mary Williamson's photograph on the day the Fox returned from the Northwest Passage.

{ John Powles Cheyne's Fox photograph. Cheyne #13A. }

{ Photograph held by Mary Williamson. Langney Archive LA/19/18. }

* * *

AFTERWORD: “TRINITY”

Knowing where the Fox docked, we now know why there were ship masts in the background of Mary's photograph: it was the Thames.

And in the background of Cheyne's photograph, we saw two buildings. The long one on the right would be part of the massive Thames Ironworks of Blackwall (or their engine supplier Ravenhill), and presumably includes the more distant smokestack. (When the Fox docked and these photographs were taken, they were in the process of constructing HMS Warrior, which survives today in Portsmouth.)

That leaves the building on the left.

In the 2nd article in this series, Cheyne’s Motion Pictures, I'd asked that anyone who runs across more Cheyne photographs to contact me.

Shaun Williams, writer of a blog about Captain Marryat (link), recently came across the Le Vesconte family’s own Cheyne stereographs set in a Newfoundland archive, St. John’s The Rooms. Shaun alerted me to this set, and I ordered new photography.

I was then primarily hunting for more of Cheyne’s rare alternates. The Le Vesconte's Fox stereograph in Newfoundland is not a new alternate of Cheyne's #13 The Fox. But when preparing to publish this article, I noticed it has a detail available nowhere else.

{ A123-012 Le Vesconte. The Rooms, St. John's, NL. }

Unlike all other Cheyne sets I've examined, the Le Vesconte family's Cheyne #13 reveals a word on the distant building on the left.

“Trinity.” And another word, illegible, on the right side – “YARDS” missing the “Y” perhaps? Or a year: “1825”? And, along the roof, shapes that resemble goblets?

The word “Trinity” was auspicious to see. Trinity is the name of the nearby Trinity Buoy Wharf, famous as the site of a lighthouse on the Thames, and not a quarter mile away from the Basin. In fact, if we could knock down that perimeter wall in Cheyne's photograph, we'd see the dead-end street leading to Trinity Buoy Wharf, sometimes known as Trinity Road.

Thus, seeing a sign for “Trinity” here is good corroborating evidence. But what is this exactly?

Looking through old maps just east of the Basin, one eventually revealed that Trinity building – and with it, the 2nd word.

{ Weller c.1862. }

The 2nd word was not “1825,” it is “Arms.” When I read this, I assumed it meant “armaments” – for ships built at the Thames Ironworks next door. But Alison instantly guessed the true meaning of the name: a pub. “The Trinity Arms.” (And this would explain the decorative goblets along the roof.)

The Trinity Arms was an East London public house between the East India Docks and the Thames Ironworks, on the street to the Trinity Buoy Wharf and lighthouse. According to the heavily-detailed websites on British pubs, no photograph of this pub is known to exist. Cheyne's is apparently the first and only surviving image of the Trinity Arms of Blackwall. (If anyone finds another, please contact us.)

{ Weller c.1862. Author image and notations. }

It's possible that a few of the sailors in Mary Williamson's Fox photograph stepped out that break in the wall to have a pint at the Trinity Arms. I'd imagine their drinks were free when it was realized who they were.

I’ve added this site to the London guide (link). It’s about 25 minutes away from the Franklin sites in Greenwich (take the DLR from Cutty Sark to East India).

The End.

– L.Z. August 4th, 2021.

Special thanks to Mary Williamson, descendant of Sir John Franklin.

* * *

+illu1.jpg)

{ Adcock 1926, Wonderful London. Author image. }

{ Click image for very high resolution. }

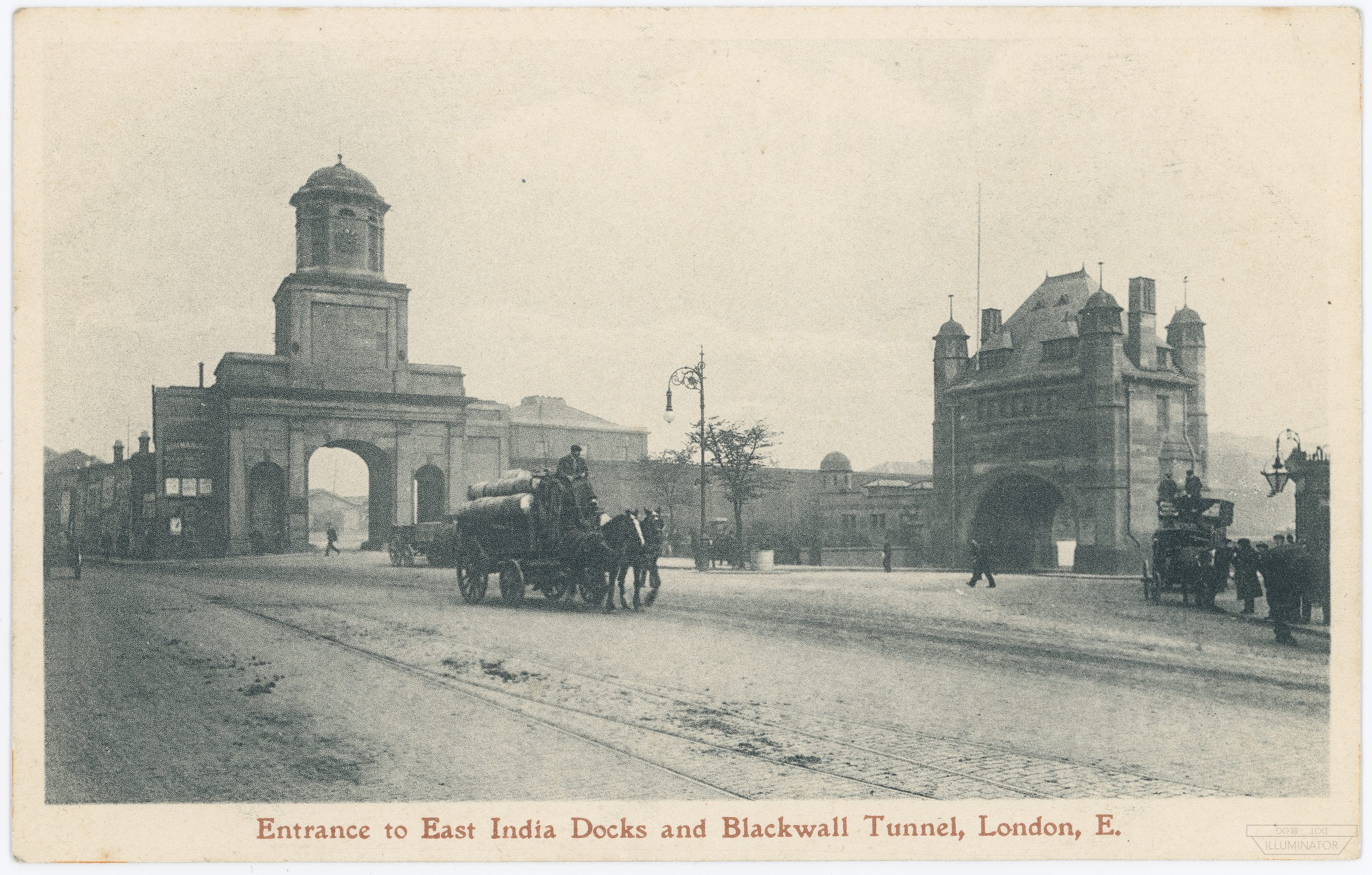

This c.1926 aerial photograph shows the East India Docks before they were filled in. The Basin already has its later ~1870s flattened eastern side (as exists today), not the curve seen in Cheyne's photograph. However, because this is pre-WW2, the old entrance that the Fox used is visibly still open to the Thames. (Click for higher resolution.)

{ The East India Docks entrance. Author image. }

On the far opposite side of the East India Docks from the Basin, this arch with clock tower (left) was the main land entrance to the East India Docks (seen distantly in the Knight 1842 sketch in the main article). It has since been torn down.

One remnant of the East India Docks entrance is preserved at the site today: the large square inscription from above the main arch.

{ Entrance inscription today. Google Street View. }

Appendix 2: The “little screw yacht” article.

The Franklin Discovery Ship.

The little screw yacht Fox, now famous, arrived in the East India Docks yesterday. She lay alongside the quay within the basin all day. Her appearance is as quiet and purpose-like as the narrative of her commander, Captain McClintock, now the theme of every tongue. She seems absolutely without a scratch on her black hull, and looks more sober, so to speak, than yachts in general. There is very little ornament about her, but what she has is in wonderfully good condition. The Fox is a round-sterned screw; has three slender, rather raking masts, is of top-sail schooner rig, and small poop aft. Indeed, everything is small about the ship save her achievements. She is rather sharp forward, and her bows are platted over with iron. As one scans the Fox more closely, we detect preparations about her for other dangers than beset the English waters. She looks not unlike a bundle of heavy handspikes, iron pointed at each end, as if for fencing off ice drift. A beautiful Esquimax [sic] canoe is lashed on her larboard quarter. A small anchor hanging over her side amidships, besides the customary one at the bow, is suggestive of dangers risked and overcome. Outside the ship, at the bottom of the ropes that stay the foremast, are a couple of ice saws ready for use. They greatly aid the mind in picturing the sort of work required of them. Another singularity in the aspect of the Fox is a pair of small antlers fixed at the end of the bowsprit – doubtless of some meaning to her crew, and connected with the discovery. The sole evidence of damage is a newly broken spar, which lies on her deck, a part of her jib-boom carried away somewhere on the English coast. In short, there lies the Fox, looking as unassuming among the surrounding craft as every hero does among the sons of men when his work is successfully achieved and his rest won.

London Star, 24 September 1859.

* * *

Appendix 3: Bibliography – in order of appearance.

SECTION: CHEYNE'S FOX STEREOGRAPH

Image: Cheyne's Fox stereograph.

Cheyne, John Powles. 1860. Fourteen Stereoscopic Slides of the Franklin Relics. Slide #13.

F6215 © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Image: Cheyne's Fox stereograph, slide #13.

Cheyne, John Powles. 1860. Fourteen Stereoscopic Slides of the Franklin Relics. Slide #13.

Tasmanian Archives: Jack Thwaites Collection; NS1155/1/20.

Image: Cheyne's booklet.

Cheyne. Descriptive catalogue of fourteen stereoscopic slides of the relics of Sir John Franklin's expedition : brought home in the "Fox" by Captain M'Clintock, in September, 1859.

SECTION: MARY'S FOX PHOTOGRAPH

Image: Mary Williamson's Fox photograph.

Langney Archive LA/19/18.

Image: Hobson & McClintock.

Illustrated London News, 1859 October 8th (McClintock) and 15th (Hobson).

Author images.

Image: Faces of the Fox's crew.

Illustrated Times, 1859 October 15, p. 256.

Author image. (Link to full illustration on twitter.)

SECTION: BLACKWALL

McClintock, Francis Leopold. The Voyage of the Fox. 1859.

McClintock's speech to the Royal Geographic Society on 1859 November 14.

Printed in various newspapers, e.g. The Chelmsford Chronicle, 1859 November 18.

"Little Screw Yacht" newspaper article #1:

Nottinghamshire Guardian, 1859 Oct 6.

Image: Bartholomew 1874.

Bartholomew, John, and William Collins Sons and Co. "Clue plan for Collins' illustrated guide to London." Map. 1874. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center.

Image: Ordnance Survey 1862-73.

Surveyed: 1862 to 1873. Ordnance Survey - Six-inch England and Wales 1842-1952, National Library of Scotland (CC-BY-NC-SA).

SECTION: THE WALLS

Image: Graham 1841.

Graham, C. B. (Curtis B.). "Plan of the East and West India Docks, 15th April 1841." Map. 1841. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center.

Image: Knight 1842.

London. Volume 3. 1842. Edited by Charles Knight.

East India Docks sketch, page 77.

Author image.

"Little Screw Yacht" newspaper article #2 (this one mentioning the Basin):

London Star, 1859 Sept 24.

SECTION: THE EAST INDIA DOCKS BASIN

Image: Basin photographs by Alison Freebairn (finger-post.blog).

SECTION: AFTERWORD "TRINITY"

Image: The Le Vesconte Cheyne stereograph of the Fox.

A123-012 Le Vesconte.

The Rooms, St. John's, Newfoundland.

Image: Map of Blackwall by Edward Weller F.R.G.S. 34 Red Lion

c.1862 from "Cassell's Complete Atlas."

SECTION: APPENDIX 1 ADDITIONAL VIEWS

Image: East India Docks and Blackwall Tunnel, postcard.

Author image.

Image: The Three Basins of the East India Docks.

Wonderful London, 1926. Edited by Adcock.

Author image.

* * *

This is Part 5 in a series revolving around Cheyne’s relic photography.

- Part 1: The Missing Toy Sledge from Erebus

- Part 2: Cheyne's Motion Pictures

- Part 3: Cheyne's Relics

- Part 4: Lost Letters of the Victory Point Record

- Part 5: Where The Fox Docked

- Part 6: Who Was Photographed With The Fox?

- Part 7: Reversing the Chronometers at the Boat Place

- Part 8: A Stained London Pocketwatch

- Part 9: (forthcoming)

– L.Z. August 4th, 2021.