By Logan Zachary. November 1st, 2021.

Acknowledgments:

Alison Freebairn

Douglas Stenton

Jeremy Michell

Shaun Williams

DJ Holzhueter

Emily Akkermans

Douglas Wamsley

Russell Taichman

Chris Valade

Peter Chrisp

Russell Potter

& Kenn Harper

Summary: A change of provenance for the Franklin Expedition chronometers found at the Erebus Bay Boat Place, with a discussion of implications for reconstructing the expedition’s demise. In addition, a relic is identified which could have named the HMS Erebus shipwreck 145 years before its discovery, and a potential link is made between an Erebus officer and a relic found at the Boat Place.

* * *

“Few can imagine how strange I feel at the loss of my chronometer; its constant ‘tick-tick’ at my right ear I thought anything but music, but now I feel lost.”

– Charles Francis Hall, searching for Franklin’s men, April 28th 1869.

{ Chronometer Arnold 2020. Author photograph. }

Arnold 2020 is a chronometer found with the skeletons under the snow at the Boat Place, its name written elegantly on the dial. A chronometer is a timepiece whose performance is of such accuracy, it can be used to determine longitude, and therefore one’s place on this planet. When a chronometer ceases ticking and goes silent, the problem is not that you’ve lost the time: you’ve lost where you are.

Arnold 2020’s protective glass is gone, its hands have been stripped away, and a patina of rust, or blood, or chocolate (or all three) now stain its face in a Rorschach pattern — an imprint of whatever it went through as the 1845 Franklin Expedition disintegrated and vanished above the Arctic Circle.

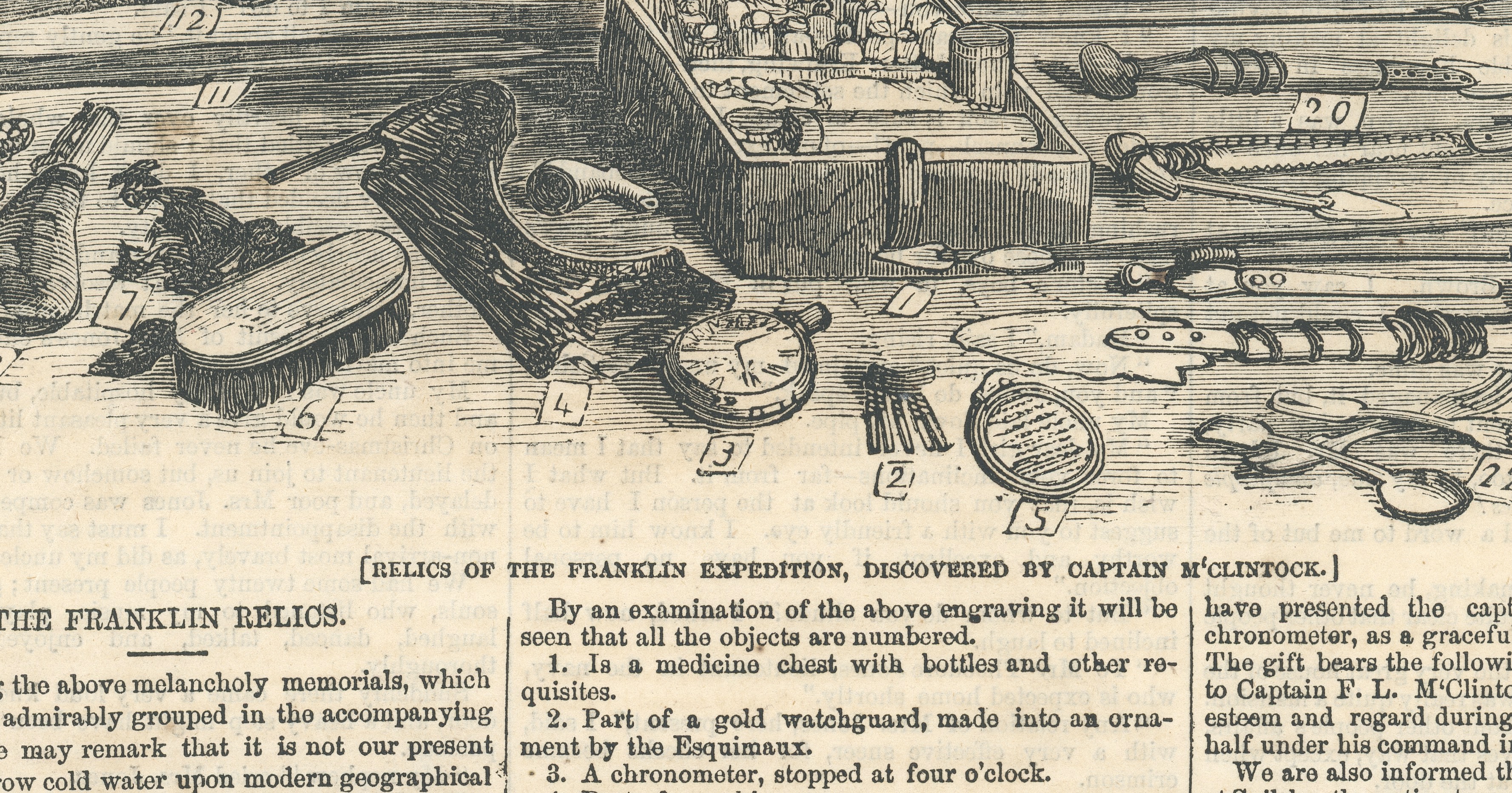

{ “The Boat Place” as imagined by Harper’s Weekly, 29 Oct 1859. }

Arnold 2020 was recovered by a search party about a decade later, buried inside a 28 ft boat just peeking above the snow. Also buried in the boat were two headless skeletons, and a seemingly-random collection of dead weight that still defies explanation: silverware, slippers, sheet-lead, two loaded guns, toothbrushes, a New Testament in French, forty pounds of chocolate, silk handkerchiefs, etc. The place is Erebus Bay, but the spot is known in Franklin circles as “the Boat Place.”

{ Boat Place location. Map from The Voyage of the Fox, 1859. }

Arnold 2020 was not alone. Nearby was a sister, a second Franklin Expedition chronometer.

The sister chronometer is instantly recognizable in Victorian sketches of Franklin relics, as her surviving hands forever show us the time of her demise: 4 o’clock.

{ The London Journal, 5 Nov 1859, p. 272. }

{ Arctic Expeditions, 1877, D. Murray Smith. }

{ Stories of North Pole Adventure, 1895, Frank Mundell. }

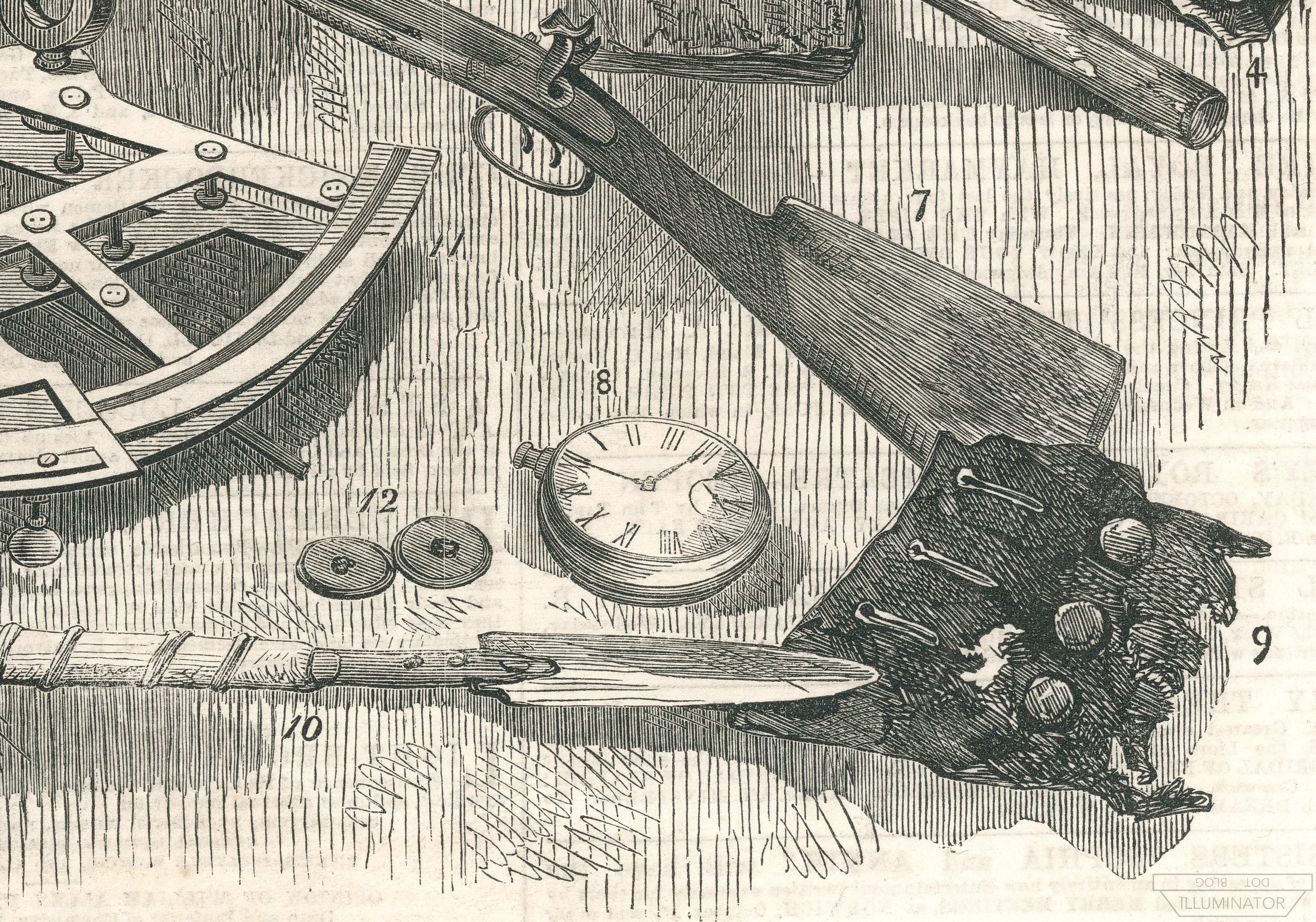

{ Illustrated London News, 15 Oct 1859. }

{ Illustrated London News, 15 Oct 1859. }

{ AAA2203 © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. }

This forever 4 o’clock chronometer is Parkinson & Frodsham 980, made in London. She is the 2nd of the two chronometers found at the Boat Place, her hands resting at 4:01 (plus a dozen or so seconds, depending on where you think the second hand came to rest).

It’s rare when we know the date that something happened on the Franklin Expedition. Here we know the time, down to the minute. And was it 4 p.m. or 4 a.m.? The latter would seem more likely for a mechanical device to stop moving, as one of the coldest hours of the night. But perhaps she was already slowing down, and one minute after 4 o’clock is only the time she thought it was when she stopped ticking.

Like Arnold 2020, her protective front glass is missing. But as we shall see, it was in fact still intact when she was recovered.

This relic, chronometer Parkinson & Frodsham 980, has a chance to tell us something more about the Franklin Expedition. And that is because P&F 980 was found with someone.

* * *

As a writer, Francis Leopold McClintock rarely makes an error. But regarding Parkinson & Frodsham 980 and the Boat Place, he makes several. In McClintock’s report to The Times, it is written that five timepieces – these two chronometers, plus three ordinary pocketwatches – were found at the boat “in a paper packet” together. And this was repeated by an unofficial catalogue written up from the display of the relics at the RUSI Museum.

However, McClintock had not been present for the discovery of the Boat Place. The chronometers were gone by the time he arrived, nearly a week later. It was his Lieutenant, William R. Hobson, that had led the search team that found the Boat Place and excavated it.

{ Lieutenant Hobson and Captain McClintock. }

Hobson’s firsthand report tells a different story: only four of the five Boat Place timepieces were found in that paper packet. One was not. Parkinson & Frodsham 980 was found in its own unique position.

{ Detail from “The Boat Place.” Harper’s Weekly, 29 Oct 1859. }

Hobson had found two skeletons, the jaws present but both skulls missing. The smaller jaw of a younger person was found near the bow, the bones scattered about – “by foxes,” Hobson surmised. Then in the stern of the boat was a second skeleton, lying transversely, the jaw being that of a large adult. This man was found with a bear skin, blankets, and a large mass of extra clothing about him.

And it was with this larger adult skeleton that chronometer Parkinson & Frodsham 980 was found. Hobson wrote that the chronometer was, “much in the position it would have been had he worn it in the waistband of his trousers in a watch pocket.” Hobson points out that this likely means the man was an officer, but, that no further details shed light on this question. The mass of clothing had belonged to several men, and had been shredded to pieces during excavation (the clothes were frozen so hard that a pickaxe was used to break into them).

Who was this sailor? Who was it that seems to have carried Parkinson & Frodsham 980 til the end?

While McClintock’s book misses the fact that P&F 980 was found with the larger skeleton, he does give us an interesting clue to the matter. With regard to Arnold 2020 and P&F 980, he writes that, “it could also be ascertained to which ship they had been issued,” and that is because, “These chronometers, according to the receipts in office, were supplied one to each ship in 1845.”

{ 1859’s The Voyage of the Fox by McClintock, page 297. }

One to each ship. One chronometer is from HMS Erebus. The other is from HMS Terror.

And there were receipts in London in 1859 showing which chronometer belonged to which ship.

{ Chronometers © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London }

{ Arnold 2020 (left), and P&F 980. }

As Hobson suggested, this man with a big jaw that carried P&F 980 until it stopped is likely to be an officer. Chronometers were government property, upon which the ship’s navigation (and thus their lives in the Northwest Passage) depended. In addition, consistent care from the same person would minimize error, and likewise an officer would prefer to keep chronometers he was familiar with. Indeed, on the Franklin Expedition were two other chronometers that the Erebus’ Graham Gore seems to have brought with from his previous voyage (see Potter 2016).

Therefore if we know which ship Parkinson & Frodsham 980 came from, we can narrow down – to less than a dozen out of 129 men – the most likely list of names for the large-jawed sailor found with this chronometer.

But here we hit a problem, for which this article has been written.

Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum has excellent public records for their Franklin relics, a model for other museums to follow. Those have shown that Arnold 2020 was issued to Erebus, and P&F 980 was issued to Terror.

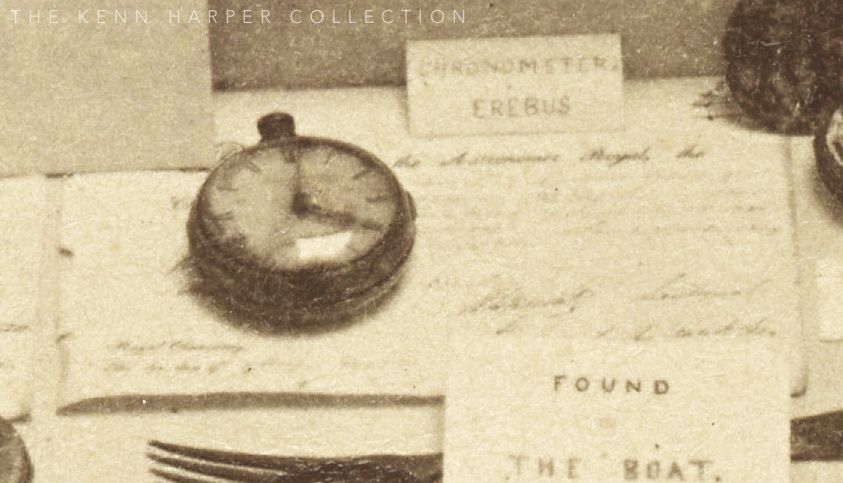

However, in 1859 when McClintock’s Franklin relics returned to London, they went on public display at the RUSI Museum. There they were photographed in stereoview by veteran Franklin searcher John Powles Cheyne. And Cheyne’s 1859 photography of the chronometers conflicts with the current records.

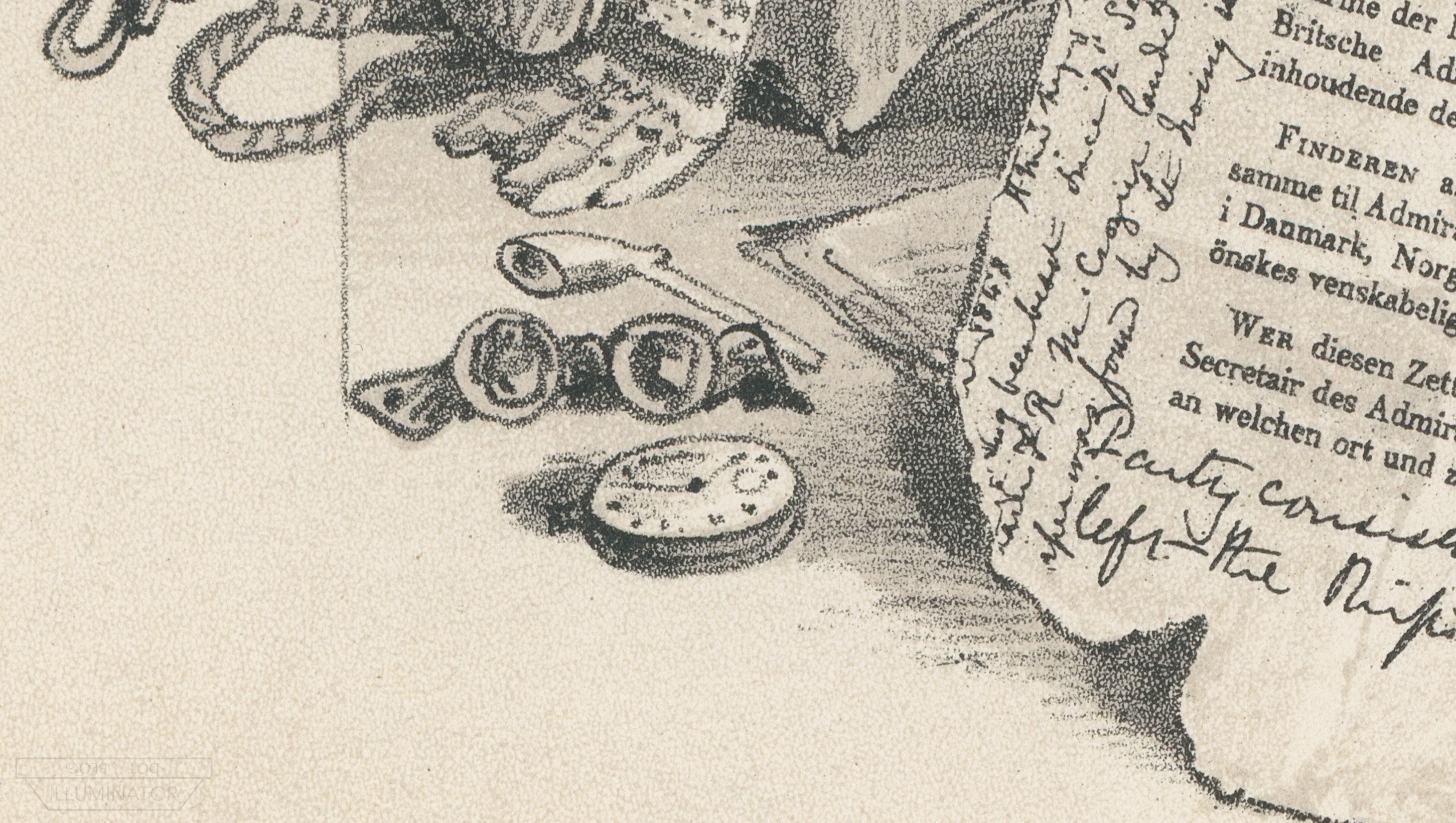

{ Stereograph by John Powles Cheyne, courtesy Kenn Harper. }

At the top-left of the museum case (above) we see the two Boat Place chronometers found by McClintock, flanked by expedition silverware. Parkinson & Frodsham 980 is, as always, instantly recognizable: she still clearly reads 4 o’clock here, even in this earliest of photographs. To the left is Arnold 2020, lying face down. Pieces of the three other pocketwatches found in the “paper packet” lie nearby, their size significantly smaller than the big chronometers.

{ Detail of the Boat Place chronometers. }

Arnold 2020 is propping up a card that reads, “CHRONOMETER TERROR.” The card behind P&F 980 says “CHRONOMETER EREBUS.” This is the opposite of what we expected to see.

And another surprise is here. A light source is visibly reflecting off P&F 980: her glass was still intact in 1859, further suggesting that she had been carried in working order.

* * *

In the summer of 2020, both Jeremy Michell (Curator of Polar Relics at Greenwich) and I were studying John Powles Cheyne’s relic photography. Michell first raised the point that the Boat Place chronometers were reversed, with P&F 980 carded for Erebus not Terror: they were labelled the wrong way around in the case.

I’d written back suggesting that Cheyne’s photograph may be right, and that we may be wrong. Granted, these ship assignments had been fixed going back to at least the 1990s, and possibly to Victorian times (see Appendix 3). But two clues kept this idea alive, through the long closure of museums and archives during the pandemic.

One: I learned that Russell Potter’s Visions of the North had an article naming the archival record for those old chronometer receipts, the ones mentioned by McClintock in his book. The receipts had survived to the present day, and were consulted a decade ago to investigate another Arnold-made chronometer (Arnold 294). They could be dusted off again to check the Boat Place chronometers.

And, Two: Following that lead, the museum’s description of one receipt said that Lieutenant John Irving had signed for Terror’s chronometers – that his signature was on the receipt.

Thanks to DJ Holzhueter’s research into John Irving of the Terror, I was already familiar with Irving’s signature. And with a squint, it looked like Irving’s signature was just to the right of Arnold 2020 in Cheyne’s stereograph – as if the original chronometer receipts were actually here, underneath the chronometers, on public display for the 1859 relics exhibition.

{ Possible chronometer receipts highlighted. }

{ Irving's signature. Photograph courtesy DJ Holzhueter. }

{ The National Archives of the UK: ADM 38/672. }

{ Possible signature of Lt. John Irving. }

If that were indeed Irving’s signature, then it becomes significantly harder to believe that the 1859 display had misplaced the chronometers: the proofs would be right before them.

Nonetheless this still seemed hard to fathom. It would mean that the wrong ships had been assigned to these relics going back a generation at least. Regardless, with museums and archives closed, it wasn’t possible to investigate this further during 2020.

When Greenwich did reopen in 2021, Alison Freebairn (Finger-Post.blog) visited the Caird Library, and she requested the original chronometer receipts for Erebus and Terror. I saw her note in my inbox the next morning. I wrote Jeremy Michell to recommend a provenance change, and I ordered museum photography of the receipts, which I can share for this article.

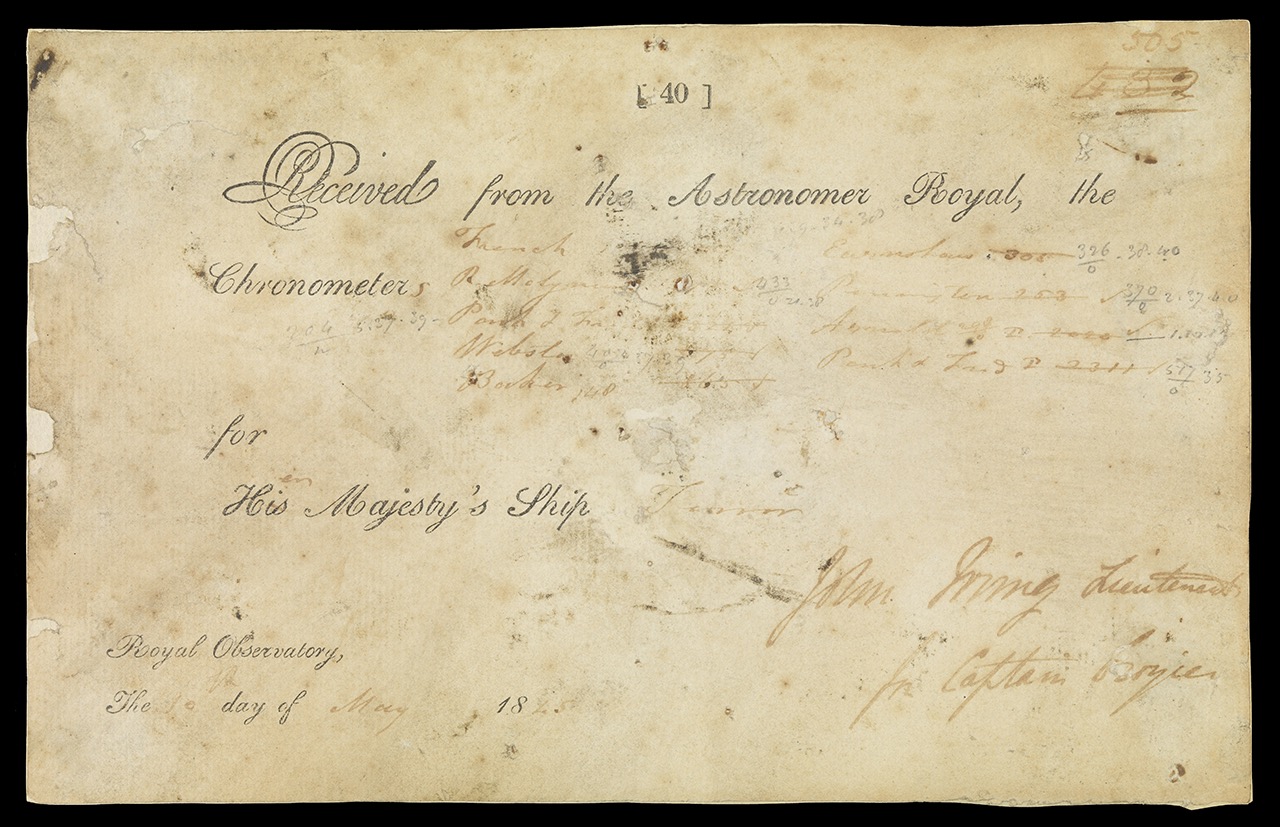

First, HMS Terror’s receipt for her chronometers:

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. }

In the lower right: “John Irving Lieutenant for Captain Crozier.” It was indeed Irving’s signature in Cheyne’s stereograph.

Above his signature is a faint handwritten list of 9 chronometers. In the 2nd column, the 2nd to last chronometer is just discernible amongst the notations: Arnold 2020.

Beneath these is written, “…for Her Majesty’s Ship Terror.”

So Arnold 2020 was in fact from Terror, not Erebus. Cheyne’s stereograph had been right, and we in the modern era had been wrong.

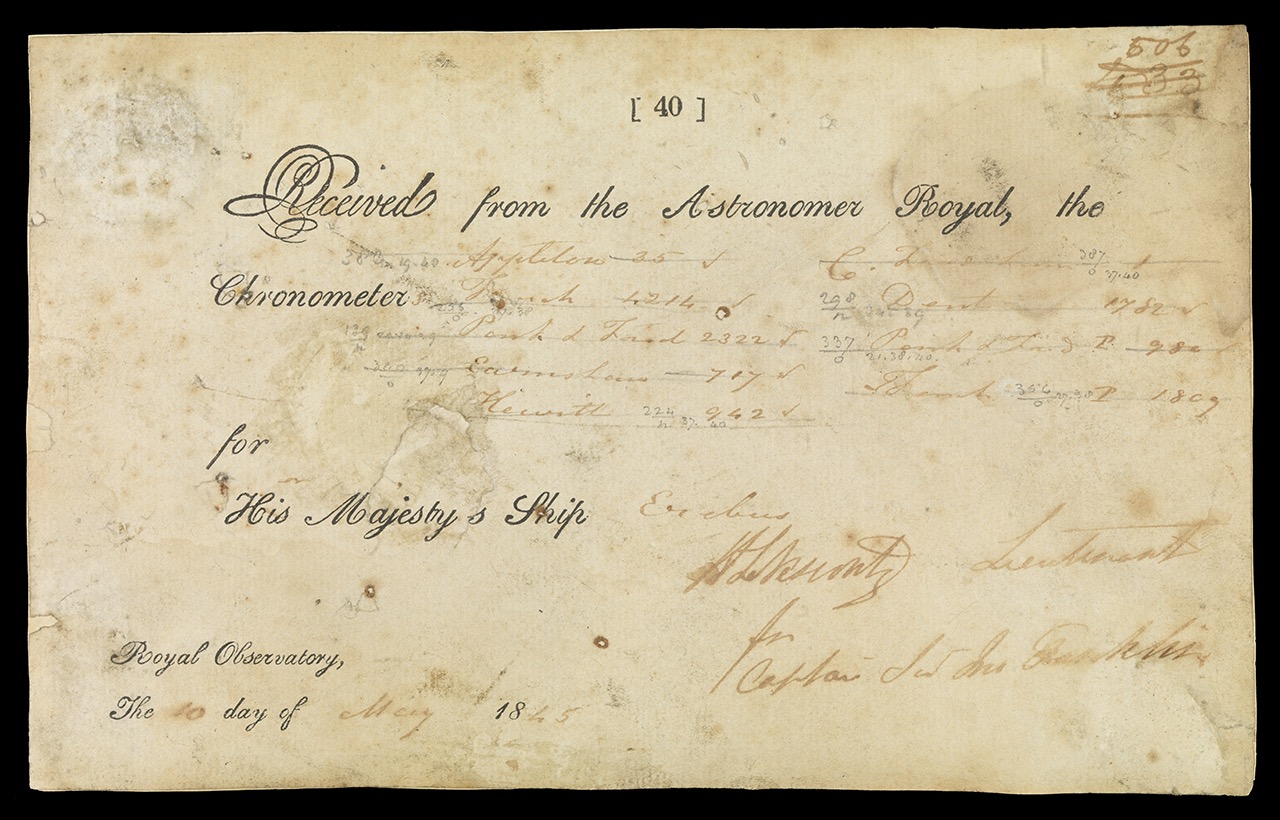

And underneath Parkinson & Frodsham 980:

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. }

In the lower right, the signature: “H Le Vesconte Lieutenant for Captain Sir John Franklin.”

The 2nd to last chronometer, in the 2nd column, is: “Park & Frod 980.”

“…for Her Majesty’s Ship Erebus.” Parkinson & Frodsham 980 is from Erebus, not Terror.

The 4 o’clock chronometer from the Boat Place, found where the pocket would be on a headless skeleton, was in fact signed out for Franklin’s flagship.

* * *

Knowing that she was assigned to Erebus, Parkinson & Frodsham 980 can now act as a kind of weathervane. This is because, despite being first discovered a century and a half ago, archaeological analysis of the Erebus Bay Boat Place has only begun in our own time. And that analysis is ongoing: as I write this in the summer of 2021, the first identification of Franklin Expedition bones by DNA was just concluded on a set found at the Boat Place. The match identified John Gregory of HMS Erebus. There are two further skeletons that may yet be named (while only two total were found in 1859, a 3rd was discovered on the site 20 years later by the Schwatka search).

If it can be determined which was the large-jawed skeleton at the boat’s stern, then the presence of chronometer P&F 980 in a pocket has different connotations based on who that is. For instance, if it is concluded that the skeleton with the big jaw was an officer from Terror, we now know that that is the wrong ship – that perhaps the officer mortality rate (noted in the Victory Point Record) had hit Erebus harder. Or, if that large-jawed skeleton turns out to be Caulker’s Mate Cornelius Hickey – carrying government-issued property from a ship he wasn’t on – that may tell us about the breakdown of command on the expedition. If Engineer John Gregory carried the chronometer, it may suggest that the loss of officers necessitated entrusting navigational equipment to men with no prior naval experience.

Critical to all such potential insights depends first on knowing which ship Parkinson & Frodsham 980 came from – which direction the weathervane is pointing. A further example of this will be discussed in Appendix 1.

In closing, it’s worth remarking that while we do not know who carried the chronometers at the end, we have seen who carried them in the beginning. The chronometer receipts for the two ships carry the same date: May 10th, 1845. Nine days before they sailed, John Irving and Henry Le Vesconte would have climbed the hill together at Greenwich’s Royal Observatory, and carried out wicker hampers filled with chronometers to measure their progress across the Northwest Passage. John Irving carried Arnold 2020 with him, and Henry Le Vesconte carried Parkinson & Frodsham 980.

As of this writing, Parkinson & Frodsham 980 is on public display at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum (link to Polar Worlds/Franklin Expedition guide).

Reversing the ship attributions of these two chronometers represents the 6th and 7th change of provenance to Franklin relics resulting from this study of John Powles Cheyne’s stereography. This is the 7th article in this series.

The End.

– L.Z. November 1st, 2021.

* * *

Appendix 1: Speculation on who would have carried P&F 980.

We now have a short list for who should have been carrying P&F 980: the Erebus officers. Understanding that the chronometer may have been carried by literally anyone as the expedition disintegrated, these are nonetheless the most likely names.

Further, if we look at the Erebus daguerreotypes board, we can immediately cross off three names: Crozier of course (from Terror), Franklin also (died 11 June 1847), and presumably “the late” Graham Gore (per the Victory Point Record).

We can also tentatively cross off the two surgeons, as they would be less likely to have navigation training.

That leaves 9 men.

{ Erebus dags with Terrors, surgeons, & the dead faded out. }

{ Image courtesy Alison Freebairn. ILN 13 Sept 1851. }

Is there any way to narrow this down further? Consider that if anyone previously attempted this, they were digging in the wrong place: they were looking at the officers of HMS Terror.

In the main article, I referenced the investigation about a decade ago into chronometer Arnold 294. Familiar to many Franklin readers, Arnold 294 was recorded as lost with Franklin’s Expedition, yet turned up for sale in the UK in the late 20th century. The name on the dial had been changed, and the mechanism showed no sign of having endured years in the Arctic. What exactly happened is still a mystery.

Looking into that mystery in 2009, Russell Potter discovered that Arnold 294’s last known voyage (on HMS Beagle) had been with one Graham Gore — familiar to Franklin readers as the Erebus’ 1st Lieutenant. It was known to Jonathan Betts at the Royal Observatory that two other chronometers on that same Beagle voyage had sailed with HMS Erebus. [Charles Francis Hall recovered the box from one of these in 1869; see Appendix 2.] The implication is that Graham Gore, embarking on a dangerous Northwest Passage attempt, requested chronometers that he knew he could trust.

As Russell Potter writes in Finding Franklin, “We know that familiarity with a timepiece was an asset – and that, indeed, some officers sought to bring along chronometers from previous voyages onto their next assignment; having at least one familiar timepiece would have been invaluable in calibrating and assessing the others.” Jonathan Betts makes the same point discussing Graham Gore in Marine Chronometers at Greenwich: “It sometimes happened that officers who had used and grown to trust certain admiralty-issue chronometers for navigation on a particular voyage requested those instruments be transferred with them to their next commission.”

This suggests a question for narrowing down our list:

Did any Erebus officer previously sail with Parkinson & Frodsham 980?

{ Le Vesconte. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. }

The Curator of Time at the Royal Observatory, Emily Akkermans, granted me access to the chronometer ledgers to study this question. Those ledgers show that, when he was in his early 20s, Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte – 2nd Lieutenant on HMS Erebus – served on the same ship as Parkinson & Frodsham 980.

That ship was HMS Endymion. Chronometer P&F 980 was signed out for Endymion by Captain Samuel Roberts in 1833. Starting late the next year, Le Vesconte served under Roberts on Endymion, from 1834-36. There’s no further information on P&F 980 until six years later, when it shows up in Portsmouth, but it’s reasonable to assume that the chronometer stayed on Endymion long enough to meet the young Le Vesconte (if it had been unsatisfactory to the Endymion sooner than that, then it would not have stayed away from the repair shop for so many years).

Further, Le Vesconte passed his exam for lieutenant while he was serving on Endymion. The stress of preparing for the navigational aspects of that exam is likely to have deeply impressed the Endymion’s chronometers into Le Vesconte’s memory.

{ Le Vesconte signature. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London }

But would any lieutenant have thought to request a chronometer he knew from 10 years earlier? In Le Vesconte’s case – and his only – he would not have had to. Because this is, in fact, not the first time we have seen Le Vesconte’s name in this article. The first time was on the chronometer receipt for HMS Erebus: it carries Le Vesconte’s signature. “H Le Vesconte Lieutenant for Captain Sir John Franklin.” Le Vesconte is the Erebus officer who signed out Parkinson & Frodsham 980. He was at Greenwich; all he needed to do while collecting chronometers at the Observatory was notice that P&F 980 was available.

While these chronometer ledgers certainly create an association of Le Vesconte with Parkinson & Frodsham 980, it does not necessarily follow that the large-jawed skeleton at the Boat Place must therefore be Le Vesconte. Furthermore, unlike P&F 980’s association with HMS Erebus as shown by the receipts, we cannot draw further conclusions in the event that the skeleton turns out to be someone not anticipated by this argument. For example, if the skeleton with the big jaw is James Fitzjames, does that suggest that Lieutenant Le Vesconte had died — on the basis that someone else was carrying P&F 980? It may well, but it would be impossible to make such a conclusion without some further evidence.

However, if the skeleton with the big jaw were to be confirmed as Henry Le Vesconte, then we could reasonably assume that he was carrying Parkinson & Frodsham 980 because he knew the chronometer from his days on the Endymion, preparing for his lieutenant’s exam.

Addendum: I sent a draft of this article to Douglas Stenton, the archeological lead of the Franklin investigation on land. He informed me that DNA evidence rules out Le Vesconte as being one of the three individuals whose remains were found at the Boat Place (site NgLj-3). Wherever Le Vesconte is, he is not here, and not with Parkinson & Frodsham 980.

Special thanks to Shaun Williams for these biographical details on Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte; I could not have connected P&F 980’s chronometer ledger to Le Vesconte’s career without his help.

Appendix 2: French 4214.

{ French 4214 © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. }

This chronometer box might have been the most famous Franklin relic of the past decade, on par with the Erebus davit pintle. It could have predicted which ship had sunk west of the Adelaide Peninsula before Parks Canada would identify her.

The critical piece of information seems to be only available on custom relic labels, written up by Charles Francis Hall. However the clue to dig up that information is right on the front of the box.

The roundel on the front reads “8 Days French 4214,” with a government broad arrow. French 4214 was the name of another chronometer from the Franklin Expedition. As mentioned in Appendix 1, this is one of the chronometers that followed Graham Gore from his previous voyage (on HMS Beagle) onto HMS Erebus.

As we have seen, the hint that chronometers can be linked to which ship they are from is in McClintock’s book. Seeing the words “French 4214” here, someone might have questioned which ship this chronometer had come from.

With the Royal Observatory receipts now before us, one can quickly find French 4214 listed: she was a chronometer from HMS Erebus.

Where, then, was this French 4214 box recovered?

There are relic labels that survive at Greenwich written by Charles Francis Hall, for artifacts that ended up with Sophia Cracroft. Here is an example of one:

(7) This Inuit knife blade given to me July 12/66 by Koong-e-ou-uk who receiving it from Too-shoo-art-thar-iu who made it of a saw blade the saw one of several that Too-shoo-art-thar-iu found in the tent where were many dead white men on King William Island.[Lance head AAA2639]

In this example, Hall lists when he was given the relic, who gave it to him, and where that person found it. A similar example is Sledge runner AAA2236: on an associated label, Hall writes when he was given the relic, who gave it to him, and where that person found it.

Such a relic label for French 4214 no longer exists. However, corresponding details for French 4214 do survive in Greenwich’s records: when Hall was given the relic, and where it was found by the Inuit.

Found by Eskimos on shore at Ookgoolik after one of Franklin’s ships had sunk. … In possession of Eskimo’s at Shepherds Bay May 17, 1869.[Curatorial records courtesy Jeremy Michell, Curator of Polar Relics.]

This level of detail is likely to have come from Hall’s original relic label. We have the place where Hall met these Inuit, the date, and where the Inuit themselves recovered the relic – all we are missing is the exact name of the Inuk who recovered French 4214.

Most important is the place: “Ookgoolik.” Ook-goo-lik was identified by Hall as corresponding to the O'Reilly Island area, just west of the Adelaide Peninsula. Roughly the same place name had been heard of (but not found) by McClintock, mentioned in his book: “Oot-loo-lik is the name of the place where she [the wreck] grounded.”

After a Franklin shipwreck was found near there on September 2nd, 2014, it would not be til a month later (October 1st) that her identification was announced as Erebus, not Terror.

{ HMS Terror presumed in 1927 to be off the Adelaide Peninsula. }

{ Gould map detail. Library & Archives Canada (source). }

The significance of French 4214 was missed by everyone, and long before our time. This is an 1869 relic. Rupert Gould would not have put a sunken Terror in that area of his 1927 map if he’d known the history of French 4214. Similarly, there would have been little reason for Schwatka to hope that an initialed board he’d found might identify which ship had sunk off the Adelaide Peninsula (see Schwatka 1880). Schwatka had remarked on the importance of identifying this southern wreck as being “the ship which completed the north-west passage” – the point so repeated by the Illustrated London News (1 January 1881). As well, Leopold McClintock, Jane Franklin, and Sophia Cracroft would all have read Hall’s custom label for the chronometer box, and seen the nameplate on the front — but, they would then have been heavily distracted by the rest of Hall’s report.

Most astonishing of all is that Hall himself never followed this lead. Identifying the ship that sank off the Adelaide Peninsula as HMS Erebus — that Franklin’s flagship had found a Northwest Passage — would have been a headline discovery coming out of his Franklin searches. Hall knew that French 4214 had come from Ook-goo-lik after a ship there had sunk. And as we have seen, the clue that a Franklin Expedition chronometer could be linked to a specific ship was right in Hall’s copy of McClintock’s book.

I believe the chronometer box for French 4214 is a strong match for this relic in the Harper’s Weekly sketch of Hall’s Franklin relics.

{ Hall’s Franklin relics. Harper's Weekly, 23 Oct 1869. }

{ Click image to download at high resolution (12 MB). }

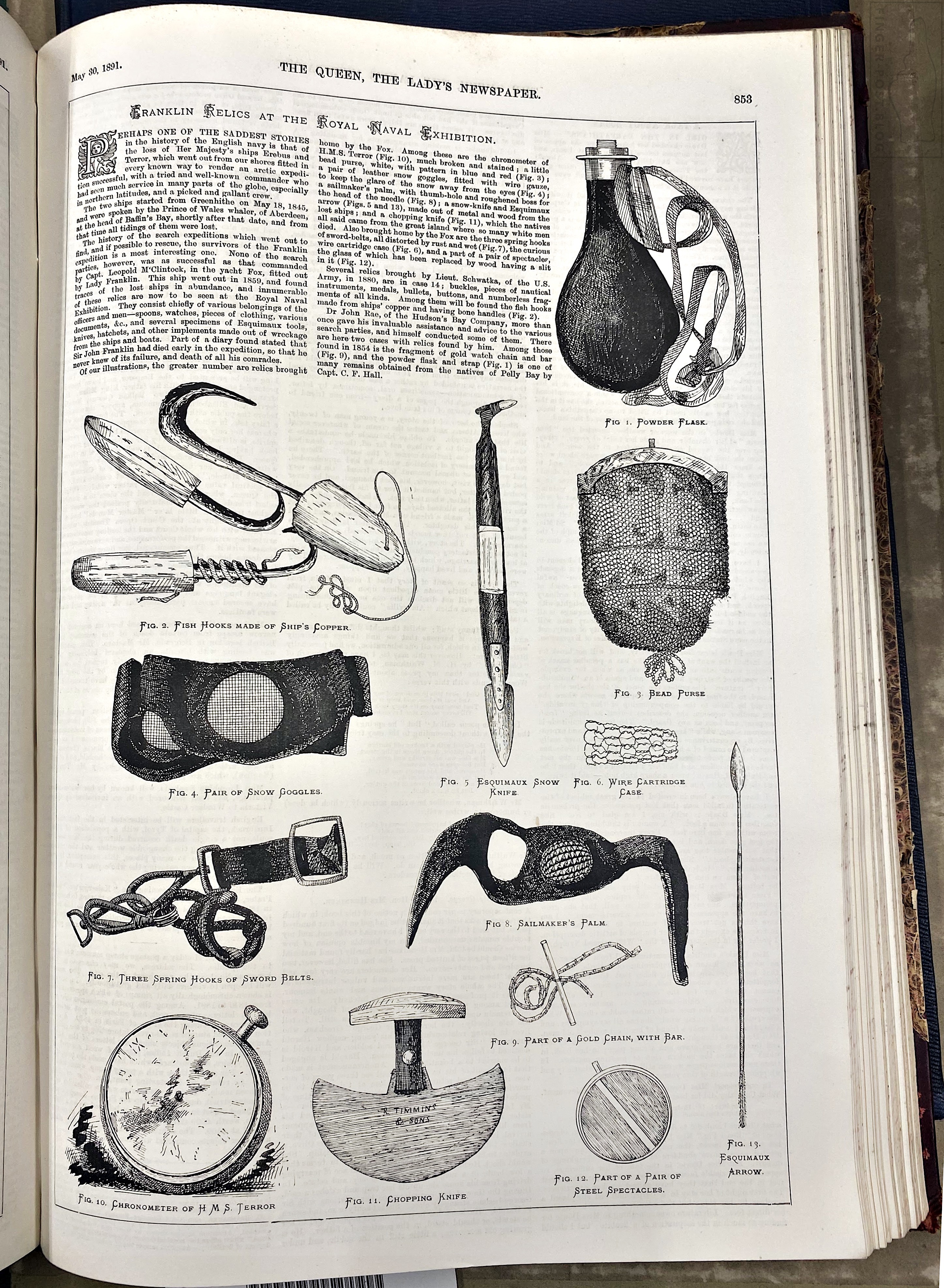

Appendix 3: The Queen relic sketch.

{ The Queen, 30 May 1891. National Library of Scotland (licence). }

{ Photograph by Alison Freebairn. }

I’ve tried to figure out when the chronometer ship attributions were accidentally reversed. They earliest date I am certain of is 1999, in Barbara Tomlinson’s relic appendix to Ann Savour’s The Search for the North West Passage. There P&F 980 was still assigned incorrectly to Terror. However, this itself suggests that the incorrect attributions were in place when Tomlinson created the AAA- catalogue names for Franklin relics — and that suggests they were in place before then even, in whatever prior records Tomlinson consulted that stopped her from reviewing the original chronometer receipts. Most likely this was documentation that followed the relics from the Royal Naval Museum, the prior home of these Franklin relics (today’s Old Royal Naval College).

And indeed, the misidentification may be older than even this suggests. In April 2019, Russell Potter discovered a sketch of Franklin relics on display at the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition in The Queen newspaper (here photographed by Alison Freebairn). One featured is a sketch of a “Chronometer of HMS. Terror.”

The watch has no hands, which might make us think that this is Arnold 2020. However, a larger detail than the hands is off here.

{ Photograph by Alison Freebairn. }

{ Chronometers © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London }

Even a child can distinguish the two Boat Place chronometers at a glance: P&F 980 has a button at the top, while Arnold 2020 has a ring. And so while The Queen’s chronometer sketch has no hands, it’s probably more significant that it has a button on top. This suggests that perhaps even in 1891, P&F 980 was already incorrectly associated with HMS Terror.

Appendix 4: The missing glass.

P&F 980’s front glass is missing today. Yet in Cheyne’s 1859 stereograph, we see the light reflection on the back of Arnold 2020 matches the shape of reflected light on the front of P&F 980. As well, the GIF animation shows that reflection moving considerably relative to P&F 980’s dial. These two details can only mean that P&F 980’s glass is present in Cheyne’s stereograph — still intact after recovery.

Two conclusions can be drawn from this.

One, the glass surviving in Cheyne’s photograph means that we can be certain the watch hands were not bumped into their current 4:01 position after recovery. The mechanism is likely fixed into that position due to exposure/corrosion, but regardless: Cheyne’s stereograph shows us that those hands were still protected when recovered. [The hands are slightly bent today, in particular the minute hand is visibly bent downwards; this must be post-recovery damage, occurring after (or as) the glass was broken.]

Two, being recovered with glass intact further suggests that P&F 980 was in working order on the sledging journey (as does its final location in the pocket position of a skeleton). In the next article in this series (add link here, Logan), I argue that Arnold 2020 did not have its glass intact upon recovery (it is indeed missing today). Perhaps the paper packet with Arnold 2020 was for broken watches, to be used as trade goods. P&F 980, glass intact and found with someone, presumably outlived whoever carried it.

I do not know when the post-recovery damage to P&F 980 might have occurred, but similar glass damage seems to have knocked out the glass of the Robinson dip circle relic from Victory Point – as well as one of its eyepieces and the bubble level on top. [To see reflections clearly moving in the dip circle's now-missing glass, observe the combined GIF of Cheyne’s McClintock photographs at the end of my article Cheyne’s Motion Pictures (link).] As both eyepieces and the bubble level are still intact in an 1878 sketch of the dip circle, the damage to it must have occurred after that date — and therefore, possibly the damage to chronometer P&F 980’s glass and hands as well. [That sketch can be seen at the top of my article The Cape Riley Rake (link).]

Incidentally, in the Boat Place chronometers GIF (above), the small spoon beneath P&F 980 (lying atop the “Found In The Boat” card) belonged to Crozier: you can clearly see his crest glinting in the reflected light. This is the only time a crest is discernible in Cheyne’s stereographs.

{ Crozier’s crest (right). Illustrated London News, 28 Oct 1854. }

Appendix 5: The boat’s ship of origin.

In The Voyage of the Fox, McClintock makes a case for the Boat Place’s boat having belonged to HMS Erebus, not Terror.

The points of evidence he lays out are as follows:

1. The majority of the silverware belonged to Erebus officers.

2. The letter “E” on the pemmican tin suggests it came from Erebus.

3. One of the watches in the paper packet bears the crest of Edward Couch from Erebus.

The chronometers don’t play a part in his argument, which is unsurprising as McClintock believes they were found in the same context (i.e., the paper packet). As he knows they belong “one to each ship,” in his mind they must cancel each other out.

However, knowing from Hobson’s report that one chronometer was found in the pocket position of one of the skeletons, the provenance of that chronometer now has a bearing on McClintock’s argument. As this article has argued, that chronometer suggests that the sailor would be from Erebus, not Terror. This would buttress McClintock’s argument.

I do think it’s worth noting that two of McClintock’s three points are not as strong as they seem. The “majority” of the silverware belonging to Erebus isn’t an overwhelming majority: it’s 6 Erebus officers vs. 3 Terror officers, plus 2 unknowns. Further, we know that Couch’s watch was found in the paper packet — with what we now know was a Terror chronometer (Arnold 2020). These two timepieces, also one to each ship, now cancel each other out (as I wrote in Appendix 4, I suspect the paper packet was for broken watches, to be used as trade goods).

Nonetheless I think McClintock’s argument that the boat belonged to HMS Erebus is a reasonable assumption. I would suggest a different configuration of evidence to support his idea:

1. One skeleton was found with a chronometer from Erebus, glass intact.

2. The letter “E” on the pemmican tin suggests it came from Erebus.

3. A slight majority of the silverware comes from Erebus officers — with, as McClintock noted, a plurality of the pieces belonging to John Franklin (8 of 26).

To this, we can now add the work by Stenton, Fratpietro, Keenleyside, & Park this year that identified the Erebus’ Engineer John Gregory as one of the three individuals at the Boat Place. However, that same research team may overturn Point #1 above, if they determine that the big-jawed skeleton at the stern is someone from HMS Terror. Overall, this boat’s provenance seems like an open question given the current evidence.

Appendix 6: On the name “the Boat Place.”

The name “Boat Place” for the site on Erebus Bay is often referenced, but I’ve never seen its source cited. A translation from Inuktitut, the term sounds slightly foreign in English; as proof, a search online for “boat place” and “tent place” returns results heavily weighted for the Franklin Expedition — not fishing and camping sites.

But for the Inuit, the term was general, not specific. Nor was the first reference to the site heard in Inuktitut: this place with an abandoned boat was not found by the Inuit until after McClintock’s search discovered it in 1859.

The oddity here is that this name “Boat Place” does not appear in the book about its own discovery, McClintock’s The Voyage of the Fox. Where does this name come from if not the search that discovered it?

In addition, the term “Boat Place” does not appear in the next major search expedition’s book: Nourse’s book on Hall’s search. [Whether or not the phrase may appear in Hall’s notebooks: the name cannot enter into broader usage if not published.]

But with Schwatka’s search (1878-80), the term “Boat Place” appears in at least three written sources on that expedition: The Search for Franklin uses the phrase several times, Gilder used it at least once – and on Klutschak’s map, it appears in German as “Bootplatz.” Schwatka also used the phrase “boat place” in his speech to the American Geographical Society.

The most consequential of all of these may be Klutschak. In 1881, the Illustrated London News ran a number of sketches by Klutschak from the expedition. On May 28th, they showed his illustration of the Boat Place. Despite having plenty of room to add explanatory text – such as referencing McClintock, Franklin, Hobson, the skeletons, etc. – their caption was just four stark words: Boat Place, Erebus Bay.

{ “Boat Place, Erebus Bay.” }

On this evidence, it would seem that the Schwatka search attached the name “Boat Place” to the Franklin Expedition site on Erebus Bay. No reference to the site by McClintock has proved as sticky as this shorthand from Inuktitut adopted by the Schwatka search.

Note: There’s an original of Klutschak’s sketch in Library And Archives Canada (#2933231, link) which shows Klutschak having written his caption as “Boatplace” – all one word, similar to his German version “Bootplatz.” Knowing Schwatka’s own German background, I began to wonder if this term “Boat Place” was a creation specific to English speakers translating Inuktitut who also spoke German. However, Douglas Wamsley pointed out to me that – while “boat place” does not appear in Nourse’s book – the terms “tenting-place” and “tent-place” do appear a number of times there in Hall’s Inuktitut translations.

Also, I have deliberately not commented here on the original Inuktitut term that would have been spoken to Hall and Schwatka. More than simply looking up a translation, this should be left to someone with considerable expertise in historical Inuktitut, including a regional understanding of the language as well.

Appendix 7: The Boat Place in Harper’s Weekly.

Click image to download the Harper’s Weekly Boat Place sketch at high resolution (17 MB).

Appendix 8: Bibliography.

Betts, Jonathan. 2017. Marine Chronometers at Greenwich.

Information on French 4214 (p. 317) and Arnold 294 (p. 257).

The wicker hamper detail on picking up chronometers at the Royal Observatory: "When issued, they were usually sent off in a padded wicker hamper." (p. 61).

Gilder, William H. 1881. Schwatka’s Search: Sledging in the Arctic in Quest of the Franklin Records.

Klutschak, Heinrich W. 1881. Als Eskimo unter den Eskimos.

Source of the Boat Place sketch captioned as “Bootplatz an der Erebus Bai.”

McClintock, F. Leopold. 1859. The Voyage of the Fox in the Arctic Seas.

McClintock, F. Leopold. 1859. "Fate of Sir John Franklin's Expedition." The Times, 23 September 1859, p. 7.

Technically the “Five watches in a paper packet” error is in a section signed by David Walker, the expedition’s surgeon. I am however crediting McClintock with the error, as the overall report is his responsibility – and because in The Voyage of the Fox, McClintock continues the error by implying that the watches were found together: “Close beside it [the skeleton] were found five watches” (p. 294).

Mundell, Frank. c.1895. Stories of North Pole Adventure.

Book source of the relics sketch image of P&F 980.

Nourse, J. E. 1879. Narrative of the Second Arctic Expedition made by Charles F. Hall.

Potter, Russell A. 2009. "A Horological Mystery." Visions of the North, 21 May 2009 (link).

Potter, Russell A. 2009. "The Missing Chronometer, Part 2." Visions of the North, 27 May 2009 (link).

Potter, Russell A. 2016. Finding Franklin: The Untold Story of a 165-Year Search.

Schwatka, Frederick. 1880. Address at the Arctic Meeting at Chickering Hall, October 28th, 1880. Printed in the Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, 1881.

On the board to identify the shipwreck west of the Adelaide Peninsula: “Among the many relics which I have of Sir John Franklin's expedition is a small board, from its appearance probably a bunk board, which once formed a permanent part of this ship, and was stripped therefrom by the Ookjoolik natives. On one side are formed the initials, L. F., by the heads of old style copper tacks. It is to be hoped that from this relic and data in possession of the British Admiralty that the ship that sank off Grant Point may be identified. I might here add that subsequent testimony of other natives corroborated this story closely, especially in regard to locality.”

Schwatka, Frederick. 1965. The Long Arctic Search: The Narrative of Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka, U.S.A., 1878-1880, Seeking the Records of the Lost Franklin Expedition.

“Among the relics found here was a board, which had been a head of a bunk or top of a box or locker, and had come from the ship which sank off Grant Pt. This board was painted black and had been covered with heavy clock oil cloth in which were driven brass-headed tacks forming the initials I. F. As the Ookjooliks from whom the present owner had obtained it, had informed him that it was torn from the interior of the ship showing it to be a permanent fixture of the vessel we had high hopes that through it (and data obtainable from the Admiralty) we would be able to identify the ship that had thus consummated the North West Passage.”

Stenton, Douglas R. 2014. "A Most Inhospitable Coast: The Report of Lieutenant William Hobson’s 1859 Search for the Franklin Expedition on King William Island." Arctic, Vol. 67, No. 4 (Dec 2014) p. 511-22 (link).

Stenton DR, Fratpietro S, Keenleyside A, Park RW. 2021. "DNA identification of a sailor from the 1845 Franklin northwest passage expedition." Polar Record 57(e14): 1–5 (link).

Stenton, Douglas R. 2021. Personal communication with the author regarding unpublished DNA evidence at NgLj-3. [See Appendix 1]

Williams, Shaun. 2021. Personal communication with the author regarding unpublished biographical details on Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte. [See Appendix 1]

Links to artifact pages at Greenwich’s site (note that at the time of writing, these pages have been offline for weeks as part of a site upgrade):

Chronometer Parkinson & Frodsham 980. AAA2203 (link).Chronometer Arnold 2020. AAA2202 (link).Chronometer box for French 4214. AAA2233 (link).Chronometer receipt for HMS Erebus. ADL/D/18 (link).Chronometer receipt for HMS Terror. ADL/D/19 (link).

Chronometer Arnold 294. ZAA0292 (link).

“And this [the chronometers together in a paper packet] was repeated by an unofficial catalogue written up from the display of the relics at the RUSI Museum.”

For information on this source, see the Appendix in my article Cheyne's Relics (link). I refer to it as “The Kelly Catalogue.” Incidentally, this catalogue’s description of the 1859 McClintock relics display at the RUSI Museum actually mentions that the chronometer receipts were displayed underneath the chronometers: “The chronometers which furnish identity and date to the expedition, bear the names of “Parkinson & Frodsham,” and “Arnold.” The receipts to the Astronomer Royal by which these chronometers are identified are dated March, 1845, and are underneath the chronometers, with those of the chronometer to each ship.”

* * *

This is Part 7 in a series revolving around Cheyne's relic photography.

- Part 1: The Missing Toy Sledge from Erebus

- Part 2: Cheyne's Motion Pictures

- Part 3: Cheyne's Relics

- Part 4: Lost Letters of the Victory Point Record

- Part 5: Where The Fox Docked

- Part 6: Who Was Photographed With The Fox?

- Part 7: Reversing the Chronometers at the Boat Place

- Part 8: A Stained London Pocketwatch

- Part 9: (forthcoming)

– LZ. November 1st, 2021.