By Logan Zachary. April 24, 2022.

Acknowledgments:

Alison Freebairn

Russell Potter

Douglas Stenton

Shane McCorristine

Allegra Rosenberg

DJ Holzhueter

Mary Williamson

Andrés Paredes

Russell Taichman

& Douglas Wamsley

On the frozen ice off King William Island in 1859, a sledge team leader sees one of his men chasing him down. He turns towards him, and when they meet, he hears of the discovery of a large boat beneath the snow, soon to become one of the most infamous sites in the Franklin Expedition’s demise.

The chasing man had left behind a companion. The companion remained waiting at the boat place — alone.

How long does it take to chase down someone out of hailing distance, when shouting their name will not stop them? In a flat white land, what distance requires physically closing with someone to get their attention? A half a mile or more? Perhaps a timeframe of 15 minutes to an hour, to reach them and then double back?

For that time period, the man’s companion stood alone at what we now know as “the Boat Place.” Would he start to excavate the snow on his own? We know what he would find underneath: the chocolate and sheet lead, the skeletons missing their skulls, The Vicar of Wakefield, the loaded guns. Would it be less frightening to stop digging and merely stand there shivering, alone in the Arctic, out of even screaming distance from the next human being? Even a quarter hour waiting alone in such a scenario would have felt endless, looking down at the edges of a nightmare beneath the snow — knowing it might become one’s own fate before escaping the Northwest Passage.

The man who waited alone at the Boat Place was George Edwards, a young carpenter on the McClintock search expedition (1857–59). He would tell his story to two people. This article revives those sources from 19th century publications. Both are very brief and imperfect; in fact, neither is longer than this introduction.

* * *

{ Lincoln’s coffin. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, 13 May 1865. }

The trail to George Edwards’ account begins with someone stuffing Franklin Expedition relics into Abraham Lincoln’s coffin.

I first read about this story on Russell Potter’s Visions of the North (17 March 2016). Potter quotes from a newspaper notice from 1865, just three sentences in length.

Interesting Relics.

Captain Parker Snow, the distinguished commander of the arctic and antarctic exploring expeditions, presented to Gen. Dix, with a view of their being interred in the coffin with the President, some interesting relics of Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated expedition. They consisted of a tattered leaf of a Prayer Book, on which the first word legible was the word “Martyr,” and a piece of fringe and some portions of uniform. These suggestive relics, which are soon to be buried out of sight, were found in a boat lying under the head of a human skeleton.

[The New York Herald, 26 April 1865.]

This is a story so unusual, it makes the presence of the giant Franklin Search relic in the Oval Office seem unremarkable. Not the least implausible detail about this story is that: the relics being given are clearly Boat Place relics, and this man – “the distinguished commander of the arctic and antarctic exploring expeditions” – should not have Boat Place relics to give away.

That man is the eccentric William Parker Snow. Despite only going on one real search, through sheer obsession Snow would weave himself into the Franklin story for the rest of his life. He will be a central figure in this story as well: to judge this story, one must judge Parker Snow.

{ William Parker Snow holding a book, 1867. (source) }

Snow was second-in-command on the Prince Albert, the only Franklin search ship from the 1850-51 squadron that threw in the towel in 1850. He later captained the only Franklin search never to enter the northern hemisphere (setting this bizarre record when his ship turned back on the coast of Australia). His final search ship never left the docks at Newcastle upon Tyne.

Snow was at one point “amanuensis” to Macaulay. At another, he ran a club in Italy. He saved a man from a shark. He managed to deeply embroil himself in the Weesy Coppin affair. And the Adam Beck affair. To free some captives held in Ethiopia, Snow offered to pose as “a kind of deaf and dumb lunatic,” infiltrate the court and then mesmerise the Emperor. It was Snow who proposed searching for Franklin with convicted criminals, because of their “inexhaustible mental resources.”

Snow claims that Charles Francis Hall once tried to strangle him — “in my own home.” Snow also claims to have applied to join the Franklin Expedition, but was rejected due to poor health, and a bad stutter; both would likely be effects of the horrific abuse he endured as a teenager at the hands of a sadistic ship captain.

Following the death of his Trafalgar-veteran father, “Boy Snow” had been raised at the orphanage for England’s sailors, in Greenwich. As this former orphanage is now Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum, it’s not impossible that the young William bunked in today’s Franklin-heavy Polar Worlds exhibit. Snow credited a gymnasium head injury while here with giving him the clairvoyance he would later use to search for the lost Expedition.

Clairvoyance he had a claim to: Parker Snow was one of those handful of individuals who correctly guessed the location of the Franklin Expedition’s demise. In 1850, Snow had written to Jane Franklin suggesting a three-pronged sledging expedition from Hudson Bay to the Magnetic Pole area — essentially the track of the future Schwatka expedition. Jane Franklin put Snow on the Prince Albert later that year, pointing the ship toward the same location from the north. Snow claims that the night before sailing, Jane Franklin took him into a private room, gave him an ear-trumpet (in case he found Sir John), then told him the story of “some dead child” (i.e., Weesy Coppin).

But the captain of Jane’s ship (Forsyth) turned the Prince Albert home rather than overwinter. Along the way back, Snow ran ashore at Cape Riley, found the note regarding Capt. Ommanney’s discovery of relics there, and scooped up a few Franklin relics of his own. Thus Parker Snow would become the first searcher ever to return Franklin relics home to Britain. But here his clairvoyance spectacularly failed him: as Snow bent down gathering relics at Cape Riley, he missed seeing the three black headstones across the bay, on the island named Beechey.

{ Snow’s map of Cape Riley. Illustrated London News, 12 Oct 1850. }

{ Not pictured: Beechey Island, just to the west. }

Despite this rich curriculum vitae, it is nevertheless startling to hear that Parker Snow landed a cameo appearance in the funeral proceedings of an assassinated United States President. And how did Snow ever get ahold of Franklin relics that were “found in a boat lying under the head of a human skeleton”?

Even casual readers of the Franklin Search saga are aware that neither boat nor skeleton would be found until the end of the 1850s, on the McClintock search. Snow wasn’t on that search, nor even in the Arctic then; he was at the RUSI Museum in London, writing up a catalogue of all their Franklin relics (see Snow 1858).

As Russell Potter comments in his article: “How Snow would have gotten hold of such things, which could only have been brought back by Sir Francis Leopold McClintock, is a puzzle -- apparently, they were accepted at face value on account of his reputation -- and, so far as anyone knows, they're still in Lincoln’s coffin to this day.”

{ A book relic from the Boat Place. }

{ Illustrated London News, 15 Oct 1859. }

Over a year after Potter published his article, Shane McCorristine (author of The Spectral Arctic) revived the topic with new research of his own. In the comments to Potter’s article, McCorristine added that he’d found a private letter from March 1860 (NU WCT 229), in which Parker Snow offered to make a gift of, “a leaf of the Prayer-Book found under the skeletons head in the boat.” As well, two months later Snow is thanked in the preface to a new book on Franklin (Browne 1860), for having made a gift to the author of, “A leaf of the Prayer-Book found with the skeletons in the boat.”

McCorristine commented: “Were these versions of the same ‘Leaf’ that was interred with Lincoln? Snow was very eccentric, but would he have manufactured these relics three times, and described them in the same way each time, five years apart? Yet, if the leaf/leaves was genuine, then how did Snow get it?”

McCorristine’s 2nd point is of note: there’s an odd consistency here. If Snow is fabricating relics, why is he risking giving each forgery an identical description? As Potter further comments, “I suspect Parker Snow might well have had a few more such leaves in reserve.”

The details remain unchanged, from private letters in 1860 to Abraham Lincoln’s funeral half a decade later. For an unaccountable and possibly invented relic, Snow’s story did not waver.

* * *

The story has stayed with me for half a decade. I drive within a mile of Lincoln’s tomb every few weeks, conscious that some 1845 Franklin Expedition relics are entombed a short walk away, underneath the ground of rural Illinois — and that no one can explain how they got there, or, if they are even genuine.

{ Lincoln’s tomb, 2021. Photographed by the author. }

Lincoln’s coffin had made a dozen stops on the way westward to Illinois, for ceremonies and public viewing of the open coffin. Snow’s relic deposit occurred at the 6th stop, which was New York City Hall. The historian John Carroll Power, first custodian of Lincoln’s tomb, gave a more detailed account of Snow’s involvement in his 1872 book on Lincoln’s funeral cortège.

About ten o’clock, on the morning of April 25, while a galaxy of distinguished officers were assembled around the coffin, Captain Parker Snow, commander of the Arctic and Antarctic expedition, presented some very singular relics. They consisted of a leaf from the book of Common Prayer and a piece of paper, on which were glued some fringes. They were found in a boat, under the skull of a skeleton which had been identified as the remains of one of Sir John Franklin’s men. The most singular thing about these relics was the fact that the only words that were preserved in a legible condition were “THE MARTYR,” in capitals. General Dix deposited these relics in the coffin. At a few minutes past eleven o’clock, the coffin was closed, preparatory to resuming its westward journey.

Here we have not only the date, but the hour: 10 o’clock, on the morning of April 25th, 1865. Unlike the New York Herald’s article, there is no ambiguity from Power about whether General Dix put the relics into the coffin: “General Dix deposited these relics in the coffin.” We also learn that “Martyr” on the relic was in capital letters, preceded by the definite article — as “THE MARTYR” — a detail that will prove crucial in identifying what book this was.

Remarkably, because this happened to occur at the coffin’s 6th stop, we have a photograph of the exact setting where the relics deposit occurred: Lincoln’s open coffin on a small balcony beneath the rotunda of New York City Hall. (This place still exists, and the exact spot is recognizable, minus the bunting.)

{ Lincoln’s open coffin at New York City Hall by Jeremiah Gurney. }

{ Courtesy the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. }

This is the only photograph of Lincoln’s open coffin. Among the many faked images of a dead Abraham Lincoln, this one alone is genuine. All copies were ordered destroyed, but one survived – rediscovered in the 1950s by a teenager. Here we see the coffin that the mysterious Franklin Expedition relics were placed into, on the balcony where Parker Snow handed them to General Dix. Within an hour afterwards, the coffin was closed in preparation to move westward toward Illinois.

* * *

If Power’s account is certain that Snow’s relics entered Lincoln’s coffin, what then can we say about the authenticity of the relics themselves?

The points by Potter and McCorristine allow us to draw convincing brackets in time for trying to learn more: the winter of 1859, from late September (the McClintock expedition’s return) to early March the next year (Snow’s letter proffering a relic leaf). If Parker Snow received Boat Place relics, he necessarily obtained them during this timeframe.

{ A book relic from the Boat Place. }

{ Le Monde Illustré, 19 Nov 1859. }

I recently picked up the trail of this story by a notice landing just outside those dates. The next year, in April of 1861, Parker Snow gave a lecture at the Athenaeum in Lancaster, England. A newspaper notice on the speech mentioned that Snow’s talk had Franklin Expedition relics on display (Lancaster Gazette, 13 April 1861).

No further details on the relics were given. But in these years, Snow was giving lectures all over England, trying to drum up support for a Franklin search of his own. Recalling the story of Lincoln’s coffin, I searched backwards through press accounts of Snow’s other speeches, reversing towards that winter of 1859.

A year backwards in time, there was indeed a description of Snow’s relics. Snow had given a talk at a school house, in the small town of Morpeth north of Newcastle. His speech was covered by the local Morpeth Herald, which ended their article thus:

Much interest was excited in the contents of a case which contained a variety of Arctic relics, including some sugar from the stores at Fury beach, a naval button, part of a prayer book, which had been found under the head of one of two skeletons in a boat belonging [to] the lost expedition, &c., &c.[Morpeth Herald, 23 June 1860.]

A prayer book found under the head of a skeleton in a boat. That matches the description of the relic to be buried with Abraham Lincoln half a decade later.

And it should be immediately noted that this gives much more credibility to Snow’s story. This is a markedly different context than a questionable relic being proffered in private letters, or placed in a coffin across the ocean. This is England, and Snow is evidently showing the Prayer Book relic across the country, in talks open to the public. If it were a counterfeit Franklin-McClintock relic, it would be exceedingly risky for Snow to open it up to repeated public inspection in this manner.

{ A prayer book and buttons from the Boat Place. }

{ Illustrated Times, 15 Oct 1859. }

Continuing to read backwards towards 1859, a few more details are revealed. One newspaper adds that, “The book was found lying open at the part where the burial service is, and upon the open page was that part which refers especially to burying sailors or others at sea” (Daily Chronicle, 1 March 1860). This is a further clue to the identity of Snow’s Prayer Book.

But the critical date is October 4, 1859. On that date — just the 11th day since the McClintock expedition ship had arrived in London — we find Parker Snow debuting the Franklin speech that he would stump the country with.

And Snow already has the Boat Place Prayer Book relic in his possession.

Remarkably, a flyer has survived for this exact speech, in Snow’s notebooks preserved at the Royal Geographical Society in London (WPS-16-2). It specifically trumpets that Snow will have Franklin relics at his lecture. [Beneath the flyer, a later notation by Snow confirms that this was the first of these lectures.]

{ “A few of the Relics will be exhibited.” A flyer for Snow’s speech. }

{ © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG). }

Snow gave the speech in London, specifically Wandsworth where he was living at the time. But the press coverage went far beyond: newspapers as far away as Ottawa and Tennessee would pick up the story of what Parker Snow said that night in London.

British newspapers politely covered all of Snow’s talking points. The international press zeroed in on one particular section, excerpted below.

The Search For Sir John Franklin.On Tuesday night Captain Parker Snow delivered a lecture on the above subject in the Literary Institution, Wandsworth. …The lecturer gave a very touching account of the discovery of the bodies in the boat, as gleaned from one of the party. Edwards, the ship’s carpenter, was the one who discovered it, and, hastily, calling his companions, he proceeded to remove the snow and ice. He describes it as the most awful moment in his life, and states that he could hardly help falling on his knees and returning thanks to the Almighty Father who had guided him thus successfully in his search. Underneath the head of one of the bodies was found the open Prayer Book, and it was necessary to chop away the book from the head, so hard was it frozen. On the hand of the other body was a mitten; and on attempting to take it off, the finger nails came away with it.… Captain Snow exhibited some leaves of the Prayer Book, a few buttons, and some other relics.[Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 8 October 1859.]

A book chopped from a skull, a mitten with fingernails still inside, the discoverer Edwards nearly dropping to his knees — these are lost details. If this story is true, then we are looking at a remnant of a firsthand account of the discovery of the Boat Place. It’s refracted through a Parker Snow speech, via a newspaper summary, but the account being repeated is from a first-person narrative: it tells us how this man Edwards felt.

But who is this Edwards?

When I first read this, I had no recollection of an “Edwards the ship’s carpenter” from the McClintock search. I had to start by reading through the personnel list from The Voyage of the Fox in the Arctic Seas.

{ Personnel list from McClintock’s The Voyage of the Fox, 1859. }

One name is a match: there are two carpenters, and one is surnamed Edwards, first name George. So, if the story is true, then this would explain how Parker Snow got ahold of Boat Place relics... but if it is true, then why are we not more familiar with this man Edwards?

First of all: Was this George Edwards even on the sledge team that discovered the Boat Place?

McClintock in The Voyage of the Fox makes this Parker Snow story seem highly unlikely. Because in fact, after George Edwards appears on the personnel list, there’s not a single other mention of his name in McClintock’s book. We hear that one of the carpenters stayed back at the ship when the sledge teams departed… and that is all. This hardly suggests that this man Edwards discovered the famous Boat Place, the site of the final dramatic scene of McClintock’s book.

{ Hobson and McClintock. Illustrated London News, 8/15 Oct 1859. }

But there is a closer source to check. In 2014, archaeologist Douglas Stenton published Lieutenant William R. Hobson’s sledging report (Stenton 2014). While McClintock had searched the frozen coastline of King William Island clockwise, Lieutenant Hobson began searching counter-clockwise, and so came upon the Boat Place a week before McClintock.

And Hobson’s report seems to pour even colder water on Snow’s story. Hobson names who discovered the Boat Place – and it is not Edwards the Carpenter: it’s Toms, Henry Toms, the Fox’s Quartermaster.

But the door is not closed on this story yet. Here (below) is the portion of Hobson’s report regarding the discovery of the Boat Place.

On the 24th [April 1859], the trend of the coast taking us far offshore, I sent Toms and Edwards to walk the coast line (I was too lame to be able to do it myself). At three PM, seeing Toms giving us chase, I turned to meet him and found that he had discovered a large boat upon the beach. I therefore ordered the tent to be pitched, and taking the small sledge and dogs, drove to the place, leaving orders for the men to follow when the tent was up.

There he is. Edwards the Carpenter is right where Parker Snow’s speech said he would be: on Hobson’s sledging party, at the discovery of the Boat Place.

Hobson’s report states that it was both Edwards and Toms, Carpenter and Quartermaster, searching the coast together that had discovered the Boat Place. Toms runs off to find Hobson, whilst Edwards stays with the boat. Hobson credits Toms, and Snow credits Edwards.

{ The Boat Place. Our World’s Great Benefactors, Drake, 1888. }

For our purposes, it does not matter which man spotted the boat first, Edwards or Toms. Hobson’s report confirms that Edwards the Carpenter is in a position consistent with Parker Snow’s story. They only differ on who they credit (and, notably, they each credit who told them the story). We now have corroboration that Edwards was indeed on Hobson’s sledging party, as well as being in position to discover the Boat Place.

This, then, is how Parker Snow got ahold of Boat Place relics. Within the first two weeks of the expedition’s return, Snow must have found Edwards amongst the Fox’s two dozen sailors. Snow could have steered the discussion toward relics by presenting Edwards with his new catalogue of them (Snow 1858), published while the expedition had been away. Then Snow got Edwards’ Boat Place story out of him, and also a few of his relics. One of those relics was a Prayer Book found with a skeleton in the boat.

And then on October 4th, Prayer Book in hand, William Parker Snow stood up in front of a London crowd and told Edwards’ story.

* * *

Nor is this the only corroboration of the Snow-Edwards story. Tugging on George Edwards’ name uncovered a parallel story: that there was someone else who pulled off Parker Snow’s same trick. Someone else figured out that it was Edwards who discovered the Boat Place, then they got Edwards’ story out of him, and they went into print with that story – and, they even got a Boat Place prayer book relic out of Edwards as well.

It was George Back.

{ George Back, circa 1865. Image courtesy Alison Freebairn. }

George Back, who ate boots with Franklin on the Coppermine Expedition, nearly wrecked HMS Terror in Hudson Bay, and is the namesake of “Back’s Fish River” – the final words from the Victory Point Record.

An account by Back of his own interview with Edwards the Carpenter has been hiding in The Nautical Magazine, from January of 1860:

Franklin’s Expedition: Another Relic.We have the melancholy gratification of preserving (exclusively of all other periodicals) the following little tale, imparting a touching fact concerning the fate of an officer of Sir John Franklin's Expedition. And it is rendered the more acceptable coming as it does authenticated by the signature of a well known naval officer celebrated in arctic history as the friend and companion of Franklin in one of his disastrous expeditions. …Weymouth, 12, Belvedere, Dec. 9th, 1859.A sailor named George Edwards, who was carpenter's mate (but acting as carpenter) of the discovery vessel Fox, under Capt. McClintock, called on me about a fortnight ago, and at my request detailed all the circumstances of his having travelled over the ice along the west side of King William Island. Lieut. Hobson, his officer, was so prostrated by scurvy as to be unable to walk and was dragged upon a sledge. While performing this duty, Edwards saw the point or end of a pole protruding above the snow. Where every object, however slight, was of more than common importance, it was immediately examined, and on removing the thick covering of snow a boat was discovered in which were two bodies.Edwards cut open the garments of one, and by the quality of the under clothing perceived that he was an officer. Between his legs was a small book of daily prayers (Blomfield's) and on the front page was written, in my own hand-writing – “Geo. Back to Graham Gore, May, 1845.” So that, if the poor remnant of humanity were not my old friend and officer on a former service, it must have been one of his shipmates.The book is now mine – a precious relic of the Franklin Expedition.Yours,George Back

There is no such relic — not in Voyage of the Fox, that is. That prayer book relic he mentions – found between the legs of a body, with an inscription by Back to Graham Gore – is not even listed in the relics appendix of McClintock’s book.

Nonetheless, that book still exists: a prayer book by Blomfield with an inscription from George Back to Graham Gore. It is today in the Franklin relics collection at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum.

{“...Private Devotion,” Graham Gore’s prayer book from George Back. }

The museum records that: “The book was bequeathed to Greenwich Hospital in 1900 by Mrs Eliza Back, the widow of the Reverend Henry Back, George Back's nephew.”

This is not something that could be fabricated: Back identifies the inscription – with his name – as being, “in my own hand-writing.” And he had gifted the book to a friend.

In addition to Back’s original inscription on the title page, a new inscription, written and signed by Edwards himself, corroborates the story from The Nautical Magazine.

{ Inscriptions in Graham Gore’s prayer book. }

Back’s dedication to Gore — very faint — is on the top of the right page: “G Back to Graham Gore May 1845.” That date is the month the Franklin Expedition sailed for the Northwest Passage, making this book a gift for the voyage. [Graham Gore had served under Back when he attempted a Northwest Passage with HMS Terror in 1836-37.]

Edwards’ inscription to Back — with the carpenter’s signature — is on the left page: “It was found by Geo Edwards Carpenter’s Mate of the Fox … near one of two Skeletons in a Boat covered by snow in Erebus Bay.”

[There’s a bit of presumption here, as Edwards lists his own name above his superior “Henery” Toms, the captain of the sledge. But this is corroborated by Hobson, who reported to McClintock that Edwards was in a “leading position” with Toms. Hobson’s report further characterized Edwards as “an invaluable man.”]

Ten years after McClintock’s Voyage of the Fox was first released, the 3rd edition would finally add Back’s prayer book to the discussion of relics discovered at the Boat Place. It slots in neatly next to the other Boat Place book dedicated to Graham Gore (Christian Melodies, to “G.G.”).

Of the prayer book, Clements Markham would write that George Back, “kept it on his drawing-room table under a glass case to the day of his death” (Markham 1909).

The handwriting of Edwards’ inscription to Back is very attractive. How would the carpenter have learned to write? McClintock had written that most of his men were Franklin search veterans. Search ships regularly held literacy schools. Digging through Royal Navy records, researcher Alison Freebairn (Finger-Post.blog) has located a George Edwards, Carpenter’s Mate in the muster book for HMS Assistance on the Belcher search (TNA ADM 38/7580). And as usual with Arctic overwinterings by the Royal Navy, a literacy school was conducted on board HMS Assistance (Belcher 1855). It is therefore likely that Edwards either learned to write, or improved his handwriting, during his first Franklin search.

The same source found by Freebairn tells us that George Edwards was 5’6” tall, with brown hair and dark hazel eyes, vaccinated and married. In his mid-20s on the Belcher search, George would have been in his early 30s at the time of the McClintock search. He was from Wyke in Dorset.

That hometown of his – Wyke – is a suburb of Weymouth, an English port on the south coast, halfway between Plymouth and Portsmouth. Having tracked him down to this corner of England, Freebairn found something more there: a pocket-sized Franklin relics exhibition in 1859.

Weymouth.Relics of the Arctic Expedition.Mr. Fairey, silversmith, of Bond-street, has exhibited in his window some interesting relics of the late Arctic expedition, brought home by Mr. George Edwards, of Wyke, who sailed in the Fox, under command of Captain M’Clintock, as ship’s carpenter. The relics are the latest memorials of the ill-fated Franklin expedition. They consisted of a black silk neckerchief, in a good state of preservation ; a cherry-stick pipe-stem with mouth-piece, a pair of scissors, an ivory-handled razor, a common jack-knife bearing the stamp on the blade “Turner and Yeomans,” a shoemaker's awl, and a prayer-book, the leaves and covers of which are in a better condition than could have been anticipated from their being so long embedded in snow. There is also a piece of rope exhibited, being a portion of one of the boat’s painters. The whole of the articles were dug from their icy resting place by Mr. Edwards himself, who can of course vouch for the authenticity and identity of the relics.[Dorset County Chronicle, 13 October 1859.]

All these relics must have been carried in Edwards’ pockets, from the Boat Place back to the Fox in Bellot Strait, roughly a 250 mile walk over three weeks – and with a scurvy-addled Lieutenant Hobson hauled on one of their sledges. [The phrase “The whole of the articles were dug from their icy resting place,” suggests that they were all from inside the Boat. The “prayer-book” and the “boat’s painter” certainly ought to be Boat Place relics, as neither books nor boat were observed at Cape Felix and Victory Point.]

While Edwards may have slowly given away these relics, they may also still exist together, covered in dust in a family attic, or a Weymouth-area historical archive.

If you have a photographic memory, you may have spotted that this is not the first time we’ve visited Weymouth in this article. Weymouth was the address from which George Back wrote his letter to The Nautical Magazine, recounting Edwards’ dropping by to give him Gore’s prayer book. Why are both these men in Weymouth in the winter of 1859? Edwards hailed from Wyke nearby, but why is George Back there with him? It was not simply to visit Edwards. A year earlier, Back had been securing donations to the Weymouth Museum (Dorset County Chronicle, 17 June 1858), and the winter following, Back’s wife Theodosia would die in Weymouth (6 January 1861) — as if the Backs had a second home on the seaside there. Alison Freebairn examined Back’s diary for this period (SPRI MS 395), and found Edwards’ visit squeezed into the margin after an uneventful entry (23 Nov 1859), suggesting Edwards knocked on Back’s door both late and unannounced.

{ Boats on a different shore: Weymouth beach, undated photo. }

{ George Back’s address marked by arrow. }

Did George Edwards just happen to find a book in the Arctic inscribed with the name of an explorer who was also his neighbor back in Weymouth?

The coincidence isn’t acknowledged by these scant sources. Nevertheless, all these scenes — George Edwards’ home in Wyke, George Back’s address in Weymouth, their meeting on the seaside, the handing over of Graham Gore’s prayer book, the Boat Place relics displayed in a window on Bond Street — all these scenes are within a mile of each other, at the mouth of the River Wey on the English Channel.

Back’s seaside address is today a hotel. The shop window where Edwards’ Boat Place relics were displayed is now an ice cream parlour.

* * *

At this point, the fantastical story of Parker Snow stuffing Franklin Expedition relics he shouldn’t possess into Abraham Lincoln’s coffin has become perfectly plausible. We now know that Snow wasn’t just talking privately about the relics: he was showing them publicly across England, for years. We know when he got them, within a two week range. We know who he got them from — and, we know how that source himself got ahold of Boat Place relics: he, Edwards, had discovered the Boat Place. Finally, we have that entire process repeating itself with Edwards and George Back – right down to the gift of a Boat Place prayer book relic.

With a high degree of confidence, we can say that the relics buried in Abraham Lincoln’s coffin are indeed genuine Franklin Expedition relics.

But this conclusion is now outshone by what was hiding behind it. This is no longer the story of a President’s coffin. We are looking at details of a lost firsthand account of the discovery of the Boat Place, by the man who discovered it.

{ The Boat Place. Thirty Years in the Arctic Regions, 1859. }

Our only other eyewitness view of this discovery has been two short paragraphs in the Hobson report, by an author who arrived third and was severely debilitated with scurvy. Every detail therefore from Edwards’ story is a bit more light into a very dark room.

But, we only have two brief summaries from others who heard Edwards’ account. Is it possible that a fuller Edwards account could ever be found – perhaps in Edward’s own words?

We have a ready approximation of what it might be like to find such a document. In 2018, Alison Freebairn uncovered an eye-witness account of the discovery of the graves on Beechey Island (Freebairn 2021). In standard histories of the Franklin search, a cairn is spotted on Beechey, and then a few days later the graves suddenly “were found.” The closest any history brings the reader to the discovery narrative is if they quote the messenger sent across the ice to alert the ships. But with the cinematic firsthand account written by searcher Robert Goodsir (tracked down by Freebairn to an Australian newspaper) we follow along as the search party discovers the pyramid of cans, then begins to race over the relics of Erebus & Terror’s 1845 winter camp — not yet realizing that the three shapes they ran towards were gravestones.

In lieu of finding such a document from Edwards the Carpenter, we are left to analyze the Snow and Back sources of his account.

{ The Boat Place. Ice-World Adventures, 1876. }

And despite the brevity of those two summaries, a number of interesting issues are raised. The most noteworthy must be that the Snow-Edwards account reports a skull present at the Boat Place: “Underneath the head of one of the bodies was found the open Prayer Book, and it was necessary to chop away the book from the head, so hard was it frozen.” This we might assume to be a mere exaggeration by Parker Snow: famously, both Boat Place skeletons were missing their skulls. Hobson at the discovery and McClintock a week later both tell us this.

And yet, over the next 20 years, subsequent searches would prove Snow/Edwards right. In-nook-poo-zhe-jook would tell Charles Francis Hall and Tookoolitoo that he saw skulls at the site. And Schwatka discovered not two but three skulls at the Boat Place (Stenton et al. 2015). In 2021, Canadian archaeologists identified one of the three as the Erebus’ John Gregory (Stenton et al. 2021). What are we to make of this? Did Parker Snow both exaggerate the story and accidentally turn out to be right? Or could Edwards have known more? What happened during the period of time that Edwards was left alone with the boat?

I will confine that discussion to an Appendix, and only to outline possibilities. The purpose of this article is to open the Edwards topic, not to close it. Moreover, it may be that in publishing this article – putting up a fingerpost pointed at Edwards the Carpenter – that someone else will uncover additional fragments of Edwards’ account.

{ The Boat Place – with skulls. Harper’s Weekly, 29 Oct 1859. }

I’d therefore like to close by focusing on the man from Wyke himself. There is one detail in Parker Snow’s retelling which we can have immediate confidence in.

“He [Edwards] describes it as the most awful moment in his life, and states that he could hardly help falling on his knees and returning thanks to the Almighty Father who had guided him thus successfully in his search.”

When Edwards makes his discovery, in his mind he George Edwards has solved the Franklin mystery. The long search for Franklin’s men is over: they’re at his feet. Consider that in this moment, Edwards knows nothing of McClintock’s discovery of the “Peglar” skeleton – which will appear first in the published narrative, yet is still a day away from actually happening. For Edwards, hearing the Victory Point Record read out was only the prelude to this moment: the discovery of the men. Every searcher would have dreamed of this scene (some literally did), of being the searcher who located the lost ones at last – and now it has happened to George Edwards, the mere carpenter on the voyage. “The most awful moment in his life...” The word “awful” has an archaic meaning, of “inspiring awe.” However, we also recognize in the modern era that search and rescue workers can experience more trauma than the people they try to save.

{ Stem of the boat discovered by Edwards. Author photograph (link). }

It may not have mattered to him, but as this long-sought discovery lay before him, Edwards would have been shocked to know that this awful moment would be lost to history. Edwards’ story would be briefly public thanks to Parker Snow and George Back in the winter of 1859. But Edwards’ name would not even be connected to his discovery in the pages of the official expedition book. Even the most ardent Franklin Expedition readers, familiar with every detail from the Boat Place, would struggle to name the carpenter from the Fox Expedition.

George Edwards is likely one of the 10 unnamed “crew” faces in Mary Williamson’s Fox photograph. We are unlikely to ever know which one he is.

The End.

– L.Z. April 24, 2022.

The Fox “wives and crew” photograph (LA/19/18) held by Franklin descendant Mary Williamson, taken upon the Fox’s return to London. The unnamed potential Fox crew faces are highlighted by arrows; for the reasoning behind this theory, see “Who Was Photographed With The Fox?” (link).

Henry Toms – co-discoverer of the Boat Place with George Edwards – is the tall man in the front row wearing a short-brimmed cap, a couple with the centermost of the five “wives,” directly below the Fox’s foremast and smokestack.

Postscript: Researcher DJ Holzhueter has found that George Edwards was “Discharged Dead at Bombay,” November 1874 (TNA ADM 188/26). Having died this young, it is significantly less likely that additional fragments of his Boat Place discovery account will ever be found. If Robert Goodsir had died at this same age, we would not have his Beechey graves discovery account.

* * *

APPENDICES

1. The Snow-Edwards Prayer Book relic.

2. The Psalm 112 relic.

3. The empty Common Prayer cover.

4. Miscellaneous notes.

5. Snow’s other relics.

6. Analysis of the Edwards account fragments.

7. George Edwards biographical notes.

8. Transcripts of the Edwards account.

9. Bibliography.

Appendix 1: The Snow-Edwards Prayer Book relic.

What ever happened to Parker Snow’s Prayer Book relic?

The relic buried with Abraham Lincoln is only described as “a leaf” — a single page. It is clear that Snow had more of this book: newspaper reports of Snow’s speeches describe him displaying “some leaves of the Prayer Book” and “part of a prayer book.”

{ An aged Snow photographed in 1893 (in The Review of Reviews). }

{ The Arctic medal would be placed on his coffin. }

Little more than a week before his own death, Parker Snow wrote to Clements Markham (then President of the Royal Geographical Society) regarding the upcoming Franklin commemoration in London. Snow was offering his Franklin lecture maps for use at the commemoration (Snow 1895). At the end of the letter, Snow made a further offer: “I have, also, a few relics.”

{ The Penny Illustrated Paper, 8 Dec 1894 (source). }

I have not found further details of what those relics were, nor if they were in fact displayed at the 1895 commemoration. Snow’s library was purchased by the Royal Geographical Society after his death; the RGS does not list a Prayer Book in their Parker Snow collection.

It is unfortunately possible that, if Snow indeed still had the Prayer Book in his possession, it may have been thrown away after his death. Without Snow to tell the story, no one might recognize the significance of a tattered Prayer Book.

However, as mentioned at the outset of this article, Shane McCorristine found evidence that Abraham Lincoln was not the only person to receive a Prayer Book leaf from Parker Snow. In the preface to an 1860 book about Franklin, one James Alexander Browne thanked Parker Snow for, “…presenting me with “A leaf of the Prayer-Book found with the skeletons in the boat," as a relic of the Franklin Expedition.” The other instance found by McCorristine (in a letter to Walter Trevelyan, 2 March 1860; NU WCT 229) is merely an offer of a leaf, whereas Browne’s statement is clear that he had indeed been given a leaf by Snow.

If Browne received a leaf, if Lincoln received another leaf, and if Trevelyan was offered a leaf, then we should assume that there might be any number of such leaves dispersed into the world by Parker Snow. However, none are currently known to be extant.

How would we recognize a Snow leaf if we saw one? Having collected the sources in this article, there are now three credible hallmarks to look for.

1. Publication date of 1845 or earlier.

2. The words “THE MARTYR” in capital letters. In the main article I mentioned this detail from Power’s 1872 book; however the same detail appeared much earlier in The New York Times (26 April 1865), the day after Snow’s relic went into Lincoln’s coffin.

3. A burial service at sea. This hallmark was seen and reported a number of times from 1860 to 1868 (Daily Chronicle, 1 March 1860; Durham County Advertiser, 9 March 1860; Bury and Norwich Post, 5 February 1861; Harper’s Weekly, 2 April 1864; unidentified newspaper, 18 January 1868).

There is a fourth potential hallmark. Both John Carroll Power and The New York Times reported the relic entering Lincoln’s coffin as coming from the Book of Common Prayer. This was puzzling to me: that only Americans should recognize the principal book of the Church of England. No English source I’d ever found had made that assessment of Snow’s Prayer Book. However, I have since learned that writing prayer book as Prayer Book (first letters capitalized) is a signifier to Anglicans that one is in fact speaking of the Book of Common Prayer. And that is how Snow’s relic is most often described: as a “Prayer Book.”

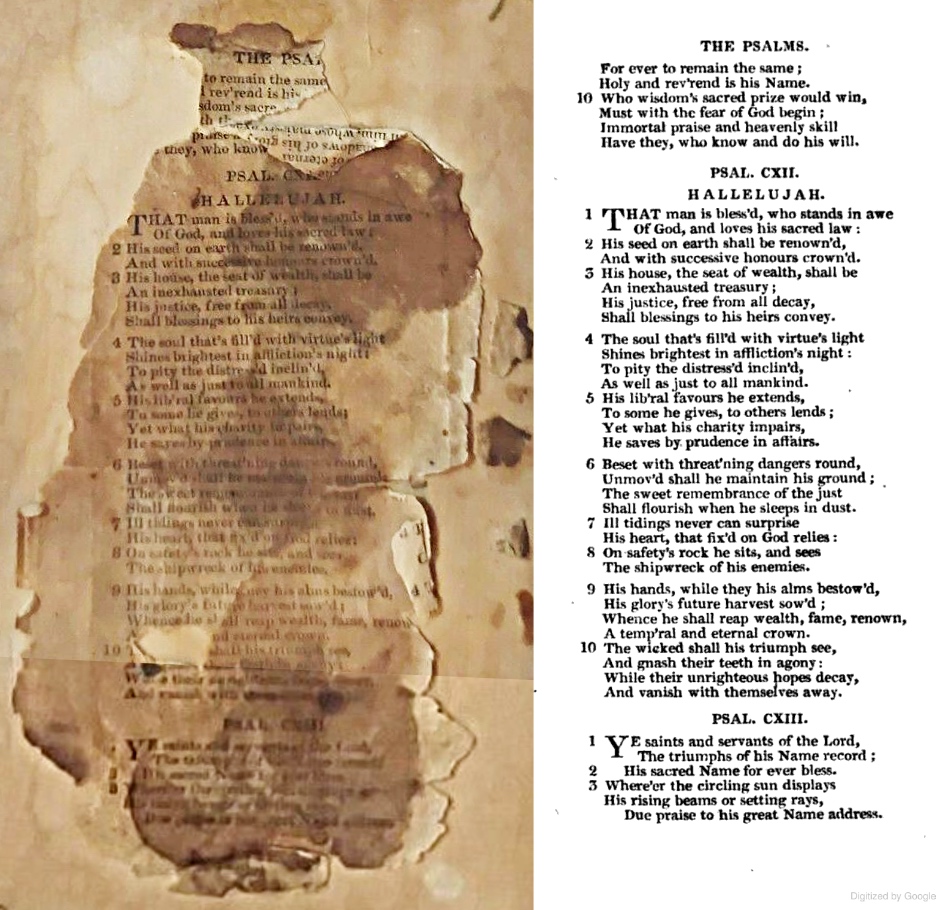

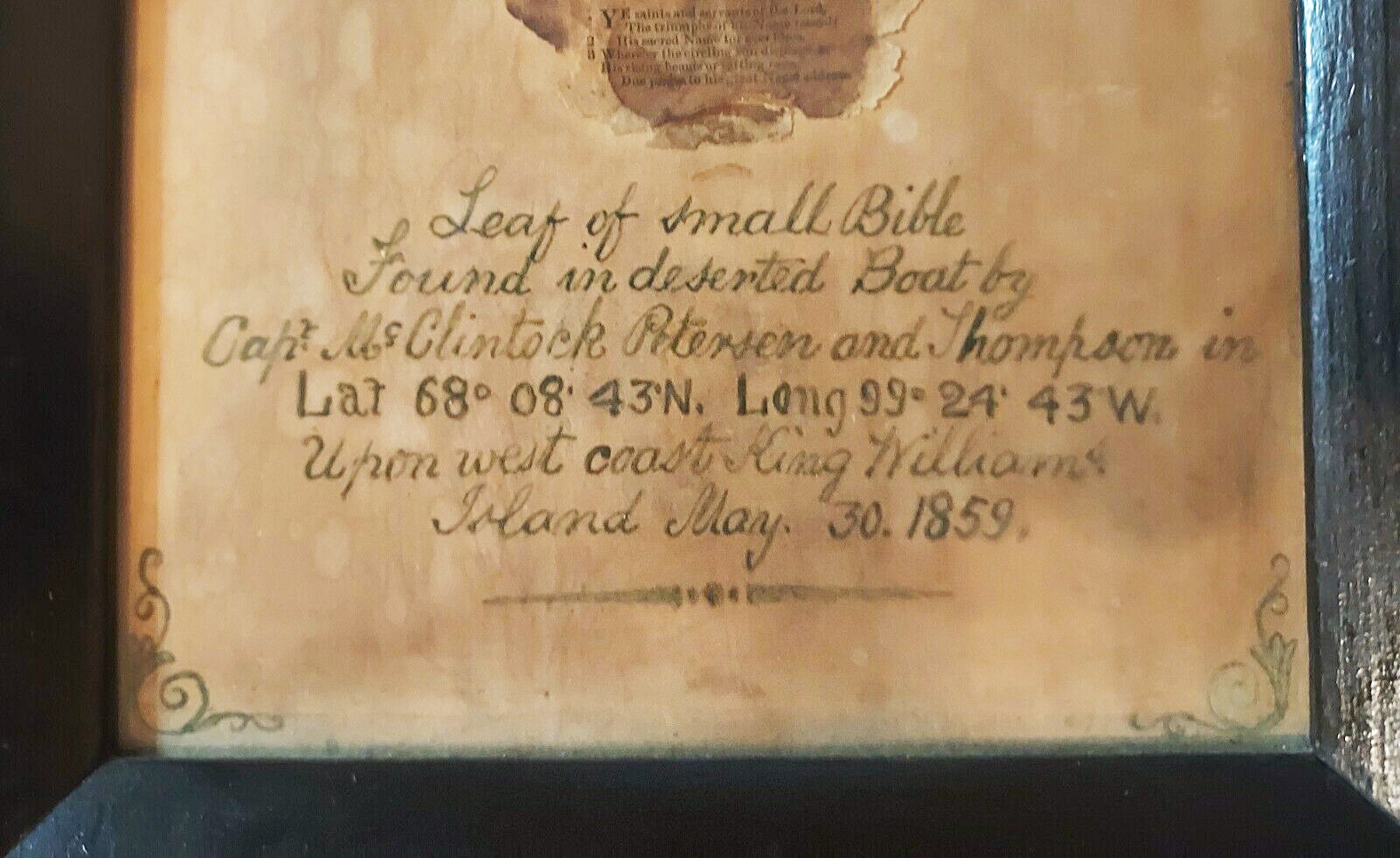

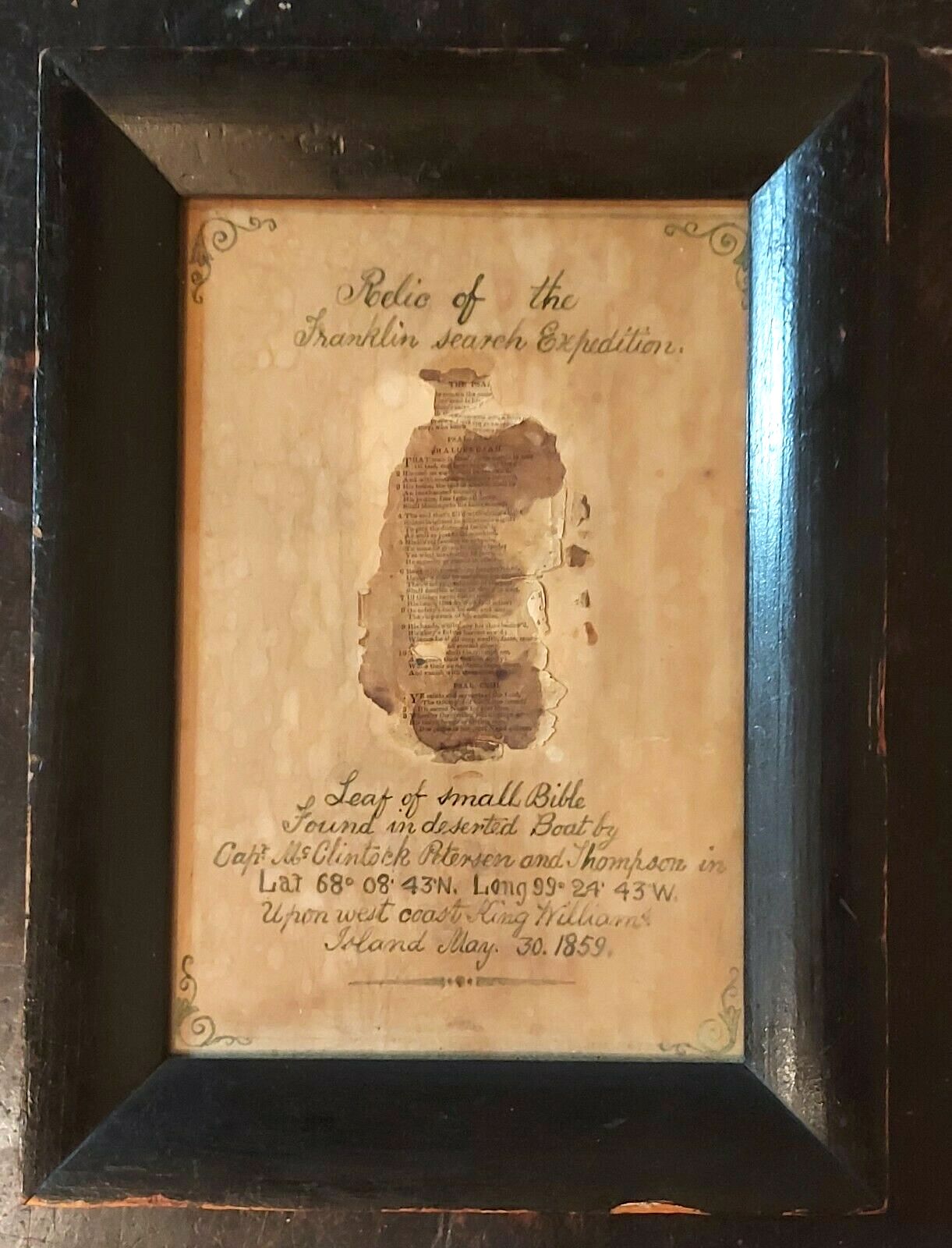

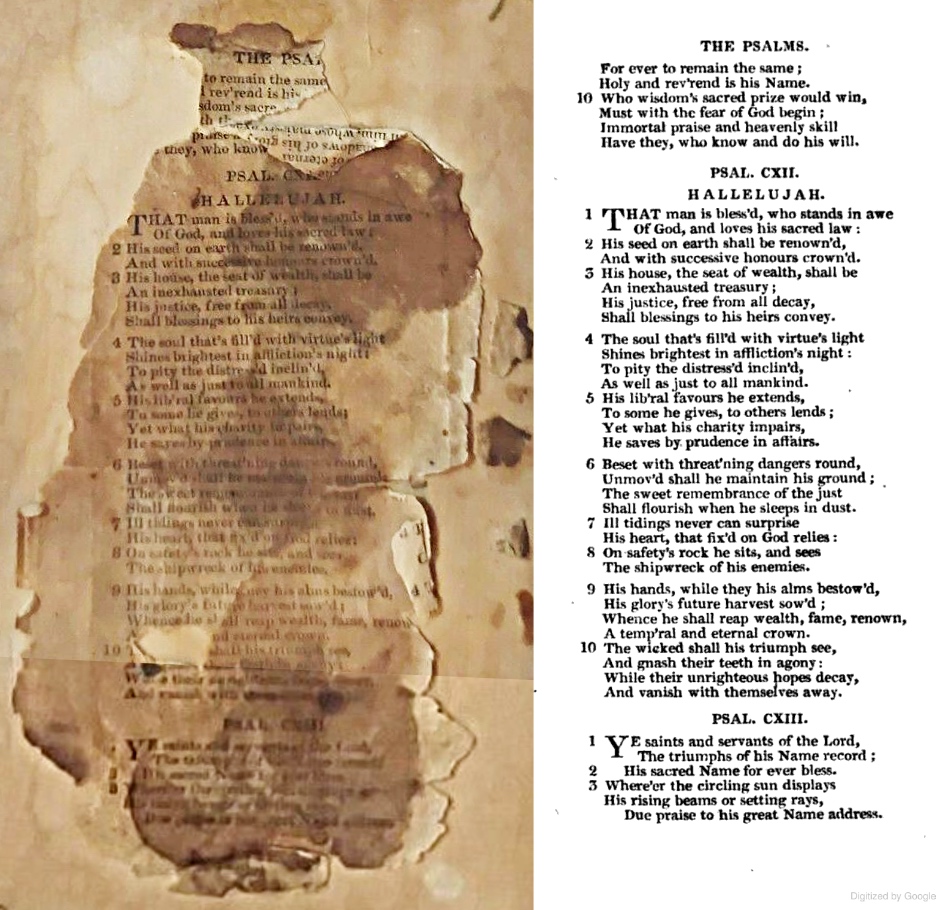

Appendix 2: The Psalm 112 relic.

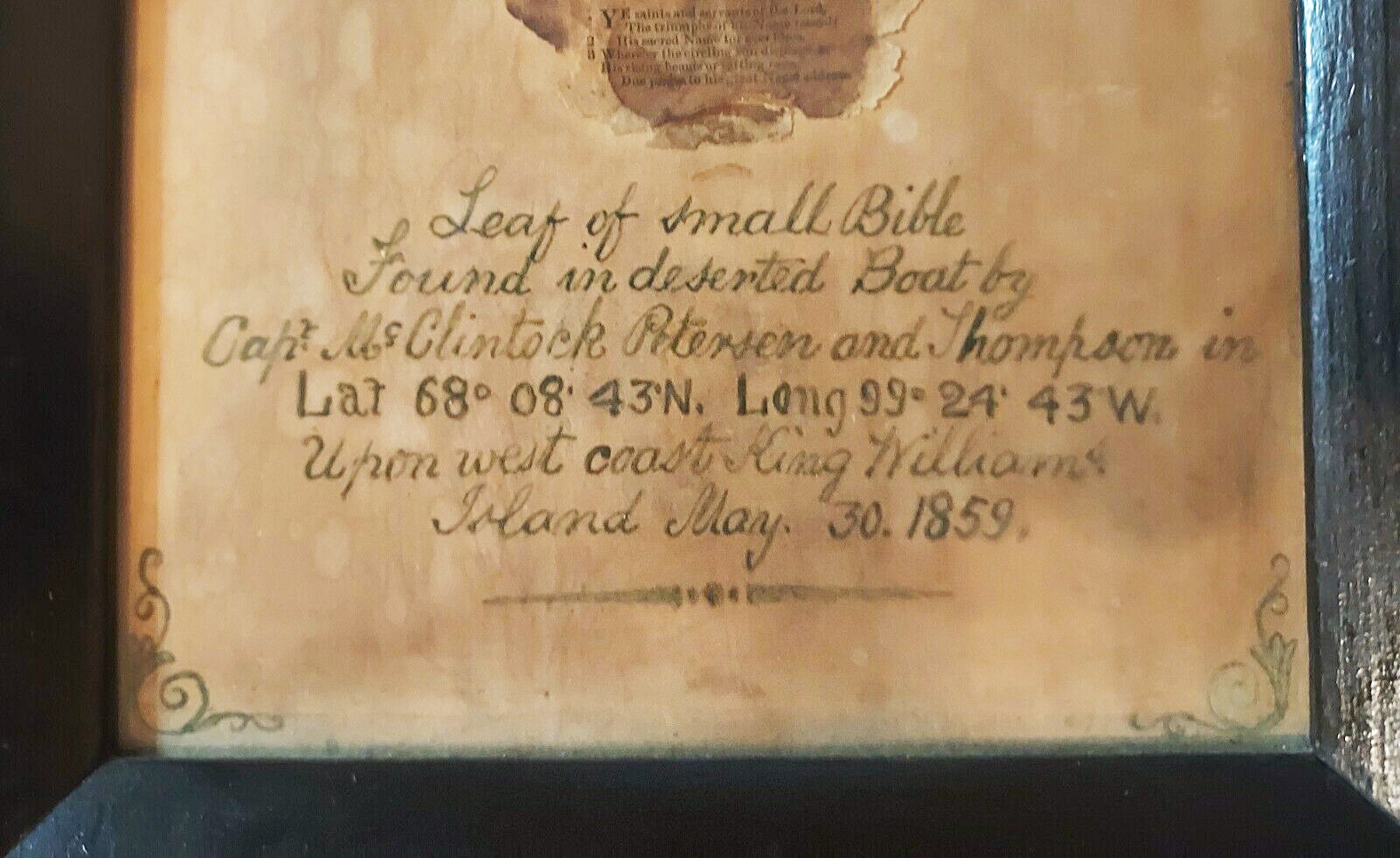

{ The newly-discovered Psalm 112 relic. }

In October of 2021, a listing appeared on the online auction site Ebay for a “Framed Relic of the Sir John Franklin Search Expedition 1845 found May 30, 1859.”

This object comes without a provenance story connecting it to Franklin or the 19th century. We must therefore evaluate it as it is.

Examining the relic itself, it is a page from the Book of Psalms — specifically Psalm 112. The text is from the Tate & Brady edition of the Psalms. Unusually, the printing abbreviates the word Psalm as “PSAL.” This is very helpful in narrowing down who printed this book. I have found the layout of the text to be an exact match for an 1829 printing of the Psalms, the publisher listed as: “Oxford: Printed at the Clarendon Press, By Samuel Collingwood and Co., Printers to the University.”

{ A page matching the Psalm 112 relic. }

{ Lower inscription on the Psalm 112 relic. }

An inscription identifies the relic as a leaf from a Bible, recovered by McClintock’s sledging party at the Boat Place.

It may be exactly as it describes itself. However, I will here make an argument that this may in fact be a page from Parker Snow’s Prayer Book relic.

The inscription identifies the leaf as coming from a small Bible. As the Tate & Brady Book of Psalms is “Fitted to the Tunes Used in Churches” (its full title), I wonder whether a Bible would include a translation of the Psalms designed for singing over historical accuracy. On this, however, I do not have any expertise.

If someone had received a leaf from Parker Snow, they may have returned home and written this inscription themselves, by referencing their copy of The Voyage of the Fox. The latitude and longitude each mistake one numeral (from McClintock’s book: Lat 69°08'43"N. Long 99°24'42”W.).

As well, while the date of May 30th here is correct, the personnel listed are only a part of McClintock’s sledge team. Suspiciously, the troika mentioned are in fact the members of the spring reconnaissance journey — not the full membership of McClintock’s party that reached the Boat Place. This oddity may suggest someone looking up details without recognizing that McClintock made two distinct sledge journeys.

Most tellingly, no donor is listed. If this had been a gift directly from one of the Fox searchers — be it McClintock, or Hobson, or George Edwards, etc — that name ought to be proudly cited with the other names listed. The lack of a donor suggests that this may have been received secondhand.

Finally: no one but Snow was known to be tearing pages out of Franklin Expedition books to make gifts. [Notable contender: John Rae once punched a disc out of a watch case relic for Lord Napier’s niece (Walpole 2017).]

As outlined in the previous Appendix, we have three principal hallmarks of Snow’s Prayer Book relic to look for: published 1845 or earlier, the words “THE MARTYR,” and a burial service at sea.

The Psalms do not contain the phrase “the martyr,” nor a burial service. However, the Book of Psalms was also included inside the Book of Common Prayer. As well, a burial service at sea can be found in the Book of Common Prayer. And, before 1859, the Book of Common Prayer would mention “the martyr,” in reference to King Charles I. [Coincidentally, the decision to remove this section from the Book of Common Prayer was in progress while McClintock and the Fox were searching for Franklin.] Perhaps tellingly, these sections often appear very close together in the organization of the Book of Common Prayer.

And, of course, the potential fourth hallmark of Snow’s relic is that the capitalized words “Prayer Book” signified the Book of Common Prayer.

Using the starting point of that same Oxford publisher that matched the Psalm 112 relic, I have found a half dozen editions of their Book of Common Prayer, looking at a decade on either side of 1829. Of that half dozen, “THE MARTYR” only appears in capitals once.

And that one occurrence is from 1829 — the same year of the matching Book of Psalms.

And why does “THE MARTYR” appear in capital letters? Because it is acting as a page heading.

{ Oxford martyrs. }

However: as I publish this article, I have been unable to find the two together. The one 1829 Oxford printing of the Book of Common Prayer that I’ve found does not use their 1829 Book of Psalms — it uses their 1828 edition Book of Psalms (and that 1828 printing does not capitalize “the martyr”).

It seems very likely that someone will eventually find a printing of the Oxford University Press 1829 Book of Common Prayer with the Oxford 1829 Book of Psalms inside it. It would then tie this Psalm 112 relic to a book with all four Snow leaf hallmarks: pre-1845, “THE MARTYR” in all capitals, a burial service at sea — and all inside a Book of Common Prayer.

At which point, the Psalm 112 relic will be a candidate for Parker Snow’s Prayer Book relic, the relic found by Edwards the Carpenter, the relic buried with Abraham Lincoln.

Still, this will not be definitive proof that the Psalm 112 relic is from Parker Snow’s Prayer Book. In my last article, a stained London pocketwatch was matched to a photograph of a far dirtier pocketwatch, on the basis that: however changed, some elements must remain the same, acting as a fingerprint or signature. Likewise, there are many unique elements to the fragile, stained, tattered condition of the Psalm 112 relic. If it is indeed a leaf from Snow’s Prayer Book, something about it ought to match other leaves from the same book — if, that is, another Snow leaf can ever be found.

Appendix 3: The empty Common Prayer cover.

Snow’s Prayer Book was only a fragment. Might it match any of the surviving Boat Place book relics at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum?

Snow’s Prayer Book was only a fragment. Might it match any of the surviving Boat Place book relics at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum?

{ The “Common Prayer” cover, front and back. }

One candidate stands out: AAA2153, an empty leather cover with the words “Common Prayer” visible on the spine.

That the pages are missing is consistent with Parker Snow only having a portion of the book with pages. The spine name would corroborate the assessment of Snow’s relic as being a Book of Common Prayer. Measurements of the new Psalm 112 relic leaf compared to this cover’s size from the museum are also within range. And as well, the condition of the cover has enough cuts, tears, and punctures to perhaps have been “chopped” at by George Edwards.

{ “Common Prayer” relic detail. }

And if this cover is from the Snow-Edwards prayer book, then there is something potentially crucial here. Parker Snow once said that, “the Prayer Book was glued together by the decomposition of the body,” that being the one identified as the officer (Durham County Advertiser, 9 March 1860). If this AAA2153 is from that same book, then there may be DNA samples surviving that could link Snow’s Prayer Book to a specific set of remains at the Boat Place. Indeed, it looks like a brown hair is visible at the top of this last photograph.

[It may be of note: for some reason, this AAA2153 was kept separate from the rest of the book relics at the 1859 RUSI Museum exhibition. It was placed alone in Case #5 – the only book in that case. The associated info card does not suggest why this distinction was made; it merely says “Prayer Book Cover.” See my October 2020 article “Cheyne’s Relics” for imagery (link).]

Appendix 4: Miscellaneous notes.

{ The Boat Place, sans Boat, by French balloonist de Fonvielle. }

{ In his book and here in Le Voleur, 4 May 1877. }

Parker Snow would eventually secure a ship for the new Franklin search his speeches were promoting: the Endeavor (previously the Triumvir). It got no closer to the Northwest Passage than Newcastle upon Tyne in 1861. When this attempt failed, Snow travelled in early 1862 to North America for a search by land, which also never materialized. Thus he ended up in the United States, initiating his feud with Charles Francis Hall, and dropping relics into Abraham Lincoln’s coffin. Snow’s wife Sarah Snow was with him for all these schemes — and she had intended to sail on the Endeavour with Snow to search for Franklin Expedition survivors in the Northwest Passage.

How did “the Boat Place” get its name? I looked into this question in Appendix 6 of my November 2021 article “Reversing the Chronometers at the Boat Place” (link).

Immediately following George Back’s letter in the January 1860 issue of The Nautical Magazine is a short review of McClintock’s expedition book, The Voyage of the Fox. That review invokes the phrase, “Man proposes but the Almighty disposes.” One wonders if Edwin Landseer had read this same review. Just a few years later, Landseer would unveil a painting evoking the final dramatic scene from The Voyage of the Fox, entitled Man Proposes, God Disposes.

{ The map from The Voyage of the Fox, 1859. }

Halfway between the Boat Place (marked “X” on the above map) and Bellot Strait is a headland named Point Edwards. In his 1909 biography of McClintock, Clements Markham states that Point Edwards was named, “after the carpenter’s mate, Hobson’s sledge” (Appendix C in Markham’s book). [And north of Point Edwards is Toms Island, named for the Quartermaster.] Markham’s book is also interesting in that he is aware that Toms and Edwards discovered the boat; he must have had access to Hobson’s report or something similar. This is Markham’s entry for Edwards in his Index: “Edwards, G., one of Hobson’s sledge crew, 221; discovered the Erebus boat, 223; carpenter's mate of the Fox, 308.”

In the past decade, a narwhal tusk cane has been at auction with an inscription in silver which reads: “Brought Home in the FOX by Geo Edwards. Sent out by Lady Franklin 1859.”

{ Illustrated London News, 12 Oct 1850. }

Above is the full article from the image seen at the start of this article: Snow’s map of Cape Riley that appeared in the Illustrated London News. [Click to load at high resolution.]

For twenty-three years from 1853, Parker Snow kept a sulphur-crested cockatoo wherever he travelled (The People, 20 April 1890). Therefore, this cockatoo was around for most of the events in this article. Tookoolitoo, Ebierbing, and Charles Francis Hall would have met the cockatoo at Snow’s home in the United States.

The historian John Carroll Power (cited in this article for writing about Snow’s coffin relic deposit) is buried a short walk away from Abraham Lincoln, in Springfield’s Oak Ridge Cemetery. His gravestone inscription records that he was, “on duty the night of Nov. 7, 1876 when ghouls attempted to steal the body of President Lincoln.”

(All photographs taken by the author in late 2021.)

William Parker Snow and his wife Sarah Snow are buried in an unmarked grave near the southeast corner of Bexleyheath Cemetery (just east of Greenwich). Their plot (OP 22) is the depression in the ground immediately to the east of the grave marked for Alice Clyne (died 1917). My thanks to Cemeteries Officer Jo Pardon for assistance in finding and confirming this grave location. I’ve taken a photograph from the west with my messenger bag sitting where the Snows’ headstone would have been (link to photo).

Appendix 5: Snow’s other relics.

Regarding Parker Snow’s other Franklin relics, while English newspapers occasionally mentioned a razor, the most extensive list I’ve found comes from the American newspaper Harper’s Weekly (2 April 1864).

THE GREAT FAIR.The “Old Curiosity Shop” will contain not a few interesting things, prominent among which will be a small collection of some relics from the Sir John Franklin expedition, exhibited by Captain Parker Snow, himself an Arctic explorer. They are mostly taken from the boat found on the west coast of King William’s Island in May, 1859. In the boat were two skeletons. One was found with the head leaning upon the hand, and in the hand a prayer-book open to the service for the burial of the dead at sea. The stained pages of that service are in this collection. There are also a rusty razor, a bit of Windsor soap, shreds of cloth and buttons, parts of a stocking, a knot of rope, an Esquimaux pipe, etc. They are all very small, and the collection is in a case which can be easily lifted. There is also some sugar in a glass vial from the “Jury” [sic] beach stores, left in 1825, and some sugar as packed for the sledges of traveling parties. A profoundly sad interest invests all of them.

A newspaper clipping in Snow’s papers mirrors this list but changes the pipe from Inuit to English (see unknown newspaper, 1864).

However, the above is not the most interesting list. Another article from an unknown newspaper in Snow’s papers (see 14 Oct 1859 in the Bibliography) reports relics at a Snow speech in Stepney, very soon after Snow obtained relics from the Fox expedition.

He then exhibited some of the relics that had been brought from the Franklin expedition, consisting of two of the leaves of a prayer-book, which was found in the boat, under the head of the skeleton; a fly-leaf from a bible belonging to Lieut. Fairholm; a fly-leaf of a prayer-book belonging to Graham Gore; a razor, and a piece of stocking, marked “W. S.”

That stocking marked “W.S.” is interesting. Such a relic also appears in Hobson’s report, found at Victory Point. Perhaps Parker Snow’s W.S. stocking was the other half of the pair. [This is also the only indication I’ve found that Edwards may also have collected relics from Victory Point, assuming Edwards is Snow’s lone relic source.] The ‘fly-leaf from a Graham Gore prayer-book’ would have been a puzzle, prior to understanding Snow’s connection to George Edwards. But the ‘Fairholme Bible’ is a mystery to me. As far as I know, it is an otherwise unknown relic. Given that two of these three relics are likely genuine, it’s a reasonable assumption that the Fairholme Bible was genuine as well. On the newspaper clipping, Snow crossed out an inaccurate word in the next line (regarding missionary Allen Gardiner); he however made no corrections to this relics list. Hopefully Edwards returned the rest of the Bible to the Fairholme family. As no books were recovered at Victory Point, the Bible presumably came from the Boat Place. And if so, then it is a further suggestion that Edwards began an excavation of the boat before Hobson arrived, as now not one but two books with the name of a lost officer are in Edwards’ private relics collection (for more on this last topic, see Appendix 6).

Appendix 6: Analysis of the Edwards account fragments.

The natural purpose of analysis is to come to conclusions — e.g., Edwards was right about the skull, or he was not. I have largely avoided doing so here: despite being discovered 163 years ago, the archaeological analysis of the Boat Place site is ongoing. Whatever can be learned from Edwards’ fragmented account must come when integrated into all other Boat Place evidence, and that evidence is not all in yet.

This section, then, will outline discrete puzzle pieces, but will not attempt to sand off rough edges in order to prematurely fit pieces into position.

As an opening example of this: the following statements from the Hobson and Edwards accounts seem to rhyme.

Hobson: “The small bones of the hands and feet remained in the mitts and stockings” (Stenton 2014).

Snow-Edwards: “On the hand of the other body was a mitten; and on attempting to take it off, the finger nails came away with it” (Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 8 October 1859).

The similarity of these statements suggests that they refer to the same experience. One of the searchers may have examined a mitten before realizing it contained human remains, and then the shock of that realization caused both narrators to recall the same detail.

However we are prevented from making further deductions, as the two accounts disagree on which skeleton the mitten was found with. Snow’s account identifies the mitten as being, “on the hand of the other body,” that is: not the one found with his Prayer Book. Further Snow speeches would specify that his Prayer Book was found with the body identified as an officer (e.g., Durham County Advertiser, 9 March 1860). Therefore, Snow identifies the mitt with the forward skeleton. But Hobson disagrees: he identifies the “bones in mitts” story with the skeleton at the stern.

Perhaps most noteworthy about the mitten story, then, is that we see Edwards echoing a unique detail from the Hobson report — a document he would not have had access to.

A second example of the Hobson and Edwards accounts rhyming is that identification of an officer. The Back-Edwards account says that, “Edwards cut open the garments of one [skeleton], and by the quality of the under clothing perceived that he was an officer” (The Nautical Magazine, January 1860). Snow’s speeches would specify this as “the fineness of the linen” (Durham County Advertiser, 9 March 1860). Hobson also identified one skeleton as an officer — but on the presence of a chronometer: “From this I think it likely the deceased may have been an officer, but I cannot pretend to say that there was anything else to lead to that conclusion.” Regarding clothing, Hobson states, “I cannot say what clothing he wore.”

Thus both accounts identify one skeleton as a potential officer, but they cite different evidence — and, Hobson specifically rules out additional evidence to support his own idea.

Hobson names which timepiece (of five present) was found with the skeleton: Parkinson & Frodsham 980, from HMS Erebus. Early photography has shown that chronometer to have had its glass intact upon recovery, further suggesting that the “officer” might have carried it in working order (Zachary 2021). Why does Edwards not include this Royal Navy chronometer in his story? And if Edwards’ detail of officer clothing is at all accurate, then why does Hobson dismiss it?

{ The officer’s cap band from the Boat Place. }

We know that potential officer clothing was found in the boat. Hobson reports collecting naval buttons with crown and anchor, as well as spring hooks for sword belts and a gold cap band (all these items survive today in the National Maritime Museum’s collection; see Bibliography). While it’s possible that an item as small as buttons may have been missed during an excavation conducted with pickaxes (the tool specified by Hobson), we should assume that the sword belt hooks and gold cap band were not found with this skeleton. They are too conspicuous to have been overlooked, especially as Hobson recovered and listed them in his report. Furthermore, there are too many spring hooks for one officer, and swords are perhaps less likely to have been worn on a desperate march to Back’s Fish River. Therefore, if we assume that these latter items were taken from the ships as trade goods, it’s possible that the golden officer buttons found in the boat were merely trade goods as well. Notably, the golden cap band is recovered without mention of a cap being attached to it. We should also consider that Hobson was himself an officer, and ought to have had a keener eye for recognizing “officer clothing” than the ship’s carpenter.

Therefore in these first two comparisons — human remains in a mitten, and the presence of an officer — the Edwards account fragments can be judged as less plausibly accurate than the Hobson report. That only fingernails would be left (and then even discovered) inside a mitten seems less likely than that their associated finger bones would still be with them. And as Hobson is very clear on which chronometer was found with the “officer” skeleton (and as we still have that very relic), it is troubling that Edwards never mentions a chronometer here — which Hobson specifically states was the only evidence present to suggest an officer identification.

This brings us to the issue where we are certain that Edwards was right, and both Hobson and McClintock were wrong: the presence of a skull.

From the Snow-Edwards account, there is not any ambiguity. Not only is the Prayer Book described as being beneath a skull, but as well the Prayer Book had to be chopped away from the skull. As stated in the main article, while Hobson and McClintock reported seeing zero skulls at the Boat Place, In-nook-poo-zhe-jook reported seeing skulls there to Charles Francis Hall and Tookoolitoo (Stenton et al. 2015). As well, the later Schwatka search (1878-80) counted three skulls at the site (Stenton et al. 2015).

Both Hobson and McClintock did report two jaw bones at the Boat Place, each associated with one of the skeletons. But a skull and a jaw are not human bones that one might easily confuse. And while a skull can effectively cover a small book, requiring chopping to peel one from the other, it’s hard to imagine a similar situation arising from only a jaw bone.

McClintock’s immediate report to the public (The Times, 23 September 1859) did not specify that the boat’s skeletons were headless; this is the likely cause of at least one contemporaneous illustrated newspaper depicting skulls (Harper’s Weekly, 29 Oct 1859). Is it possible, therefore, that Snow’s skull was a false detail that he picked up from illustrated newspapers? The early date of Snow’s first speech, on October 4th, seems to preclude this. The Illustrated London News didn’t begin publishing Fox Expedition scene sketches until October 8th, with most arriving on the 15th. The only Fox Expedition illustrations printed earlier than Snow’s debut speech seem to be the facsimiles of the Victory Point Record (printed in various newspapers on October 1st).

{ The Boat Place in Harper’s Weekly, 29 Oct 1859. }

Can it be possible, then, for Edwards to have witnessed a skull in the boat that Hobson and McClintock did not?

For this to occur, Edwards would have to have removed the skull from the locale. And remarkably, we have to concede that this is technically possible: both Snow and Hobson report that, for some unknown amount of time, Edwards was alone at the Boat Place site.

What motive could Edwards have for removing a skull? One is evident from the text: the potential mutilation of the skull by chopping at it, as a disrespectful and possibly damaging act. Perhaps Edwards had begun to dig along the inner edge of the boat, and came upon the skull with a book beneath it. In his haste to seize what he believed may be a private journal – solving the Franklin mystery – he broke away the head from the body, and chopped the book from the head. Then, in embarrassment or horror at seeing he’d committed this act only to retrieve a Prayer Book, he hid the evidence — burying the severed skull away under the snow before Toms with Hobson returned.

While not impossible, this seems on the outer edge of likelihood. It also requires that, contrary to an inclination to hide evidence of his act, Edwards must then confess his story to Parker Snow in London upon his return. But confession of one’s actions is nothing unusual. And while taking away the skull from a body is itself a further act of desecration, we do not know how much flesh might still have been on these “skeletons” (particularly if buried under a heap of clothing). In fact, in Back’s letter and Snow’s initial speech, the word “skeleton” never appears: the term used is “bodies.” [McClintock used “skeletons;” The Times, 23 Sept 1859.] It is a very different thing to nick a skull with a knife’s blade than to be chopping into hair and flesh. In an early speech, Parker Snow stated that pages of the Prayer Book were “glued together by the decomposition of the body” (Durham County Advertiser, 9 March 1860). It is impossible to imagine what Edwards went through in such a scene, or to rule out erratic behavior in facing this situation. And he was alone.

Setting aside any motive for such an act, then, one way to read Hobson’s narrative may be that the site was untouched when Hobson arrived.

On reaching the spot, I found a large boat entirely embedded in snow, above which nothing of her was visible but a portion of her port gunwale, elevated above the other by the boat’s heeling considerably to starboard. … Digging her out was, of course, a work of time, but on throwing out a few shovels full of snow, wooden paddles were found which answered the purpose of shovels and all hands were able to work at it.

At a glance, this can be read as implying that Edwards had touched nothing while he waited for Toms and Hobson to return.

However, Hobson is writing well after the fact, not in the moment. And Hobson’s purpose here is to recreate the original scene for McClintock; he may not bother to mention any minor excavation that Edwards might have begun working on. To use a modern analogy: the 28 foot boat is the equivalent in length of a trailer camper, or two cars parked end to end. Edwards could have been digging only in the boot/trunk of one of those cars, leaving the majority of the site still untouched beneath the snow when Hobson arrived. In this sense, it’s noteworthy that “on reaching the spot,” Hobson identifies the visible gunwale as the port not the starboard side. This seems like a fact that Hobson wouldn’t be certain of until after the bow or stern were uncovered (unless, of course, they already had been — by Edwards).

Looking at the situation from what we know of Edwards’ other behavior during the search: it is unlikely that someone about to secret away relics for himself — including one naming a lost officer — would be too hesitant to begin the excavation immediately, alone. And this especially when Edwards knows that his officer is lame, and when that officer assessed Edwards as taking a leadership role in the search.

Therefore, while a quick read of Hobson’s report suggests Edwards may have initially touched nothing, it is more accurate to say that the report does not address the issue. And, as noted earlier, a motive for Edwards to remove a skull from the boat is not unimaginable, however unlikely. As well, Edwards had the opportunity to commit such an act, as he spent some amount of time alone at the site.

Having generously considered such scenarios, it is clear that the most plausible explanation for the skull in the Snow-Edwards account must be that: either Snow or Edwards invented a skull at the Boat Place, which just happened to later be proved correct. It is no great feat to imagine a skull at a site where skeletons are present. And the younger skeleton at the bow already establishes a precedent for skulls being removed from the boat by (presumably) animals. Perhaps the Prayer Book was found frozen in the spot where the skeleton’s missing head ought to have lain — and then Parker Snow misremembered or exaggerated this from “found frozen where the skull should be” to “found frozen to a skull.”

As Edwards was there, he would certainly know if a skull had been found. But Parker Snow was not there, and only heard the details secondhand. As well, Parker Snow has an obvious motive for sensationalizing his speech: to generate better press coverage, as he was ultimately trying to raise funding for a Franklin search of his own.

However, having just proved Snow’s dubious Lincoln coffin relics to be genuine in this same article, it would be rash to immediately return to dismissing Snow’s credibility the moment the story seems improbable — and this especially when we know that Schwatka would prove that skulls were indeed present.

And, there is a further wrinkle in attempting to dismiss this point, an echo of the issue from the outset of this article: Parker Snow did not stop telling this story.

When this began in late 1859, it would have been trivial to apply social pressure on Snow from McClintock, Hobson, Jane Franklin, George Edwards, etc., to have Snow stop telling a disturbing and falsely exaggerated story of books chopped from heads. Indeed, the power of exactly this sort of pressure is manifest in the next year, when Parker Snow is taking pains to correct newspapers that Jane Franklin had not in fact been financially supporting his proposed new Franklin search (Morning Advertiser, 29 May 1860; Evening Standard, 24 Oct 1860).

And Snow did at the time make public corrections regarding these speeches. As soon as October 15th of 1859, there is a letter to the editor by Snow (Morning Advertiser) making specific corrections — and, he mentions relics. But the corrections are mostly concerned with other issues, and the relics correction is so brief and vague as to be indecipherable: “The subject of Arctic Exploration is one so extensive that I had to go through my lecture very hurriedly. Hence the mistake in confounding my remarks upon the arduous labours of others with what I said of my own opinions; also as regards the various relics obtained at the several places.”

“The various relics obtained at the several places.” Whatever this means, it is nevertheless true that Parker Snow went on telling the story of the Prayer Book frozen to the skull. He did seem to drop Edwards’ name from his speeches, and perhaps Edwards requested this. Otherwise, Snow continued to tell the story for at least the next eight years (the latest appearance in newspapers I have found is January 18, 1868), and no one from the expedition seems to have ever written a public letter correcting or condemning him.

Indeed, just a month after making worldwide news with Edwards’ story, in November of 1859 we find Parker Snow working publicly with Leopold McClintock, assisting him with his presentation at Burlington House to the Royal Geographical Society: “The paper [McClintock’s speech] was illustrated and explained by diagrams and drawings prepared by Captain R. Collinson, R.N., and Mr. Parker Snow, showing the route taken by the expedition...” (Express, 15 Nov 1859).

If Parker Snow had been telling a gruesome fabrication regarding McClintock’s own expedition, then why would he be given the high-profile credibility of assisting McClintock at his Royal Geographical Society speech? Snow was stumping the country with his macabre tale of a book chopped from a skull both before and after appearing with McClintock at Burlington House.

I will not here attempt to resolve these contradictions. This article is not the place to force a resolution, as we are neither at the end of the archaeological investigation of the Boat Place site, nor the search for further Edwards account fragments.

And so in closing, to step back from this discussion of fine-grained details, there is one way to assess and integrate Edwards’ account immediately: as a broad confirmation of Hobson’s report.

This is more welcome than it might seem. A close read of McClintock’s narrative shows him contradicting Hobson’s report on several points. This is astonishing as McClintock had not been present at the discovery, and also as he would have had Hobson’s report before him as he finished writing and editing his book.

In McClintock’s narrative, it is the younger skeleton at the boat’s bow that is identified as the officer — not the skeleton at the stern. Regarding the disturbed bones of the forward skeleton, McClintock graduates Hobson’s supposed culprit “foxes” up to “large and powerful animals, probably wolves.” And McClintock misses the fact that one chronometer was found in the pocket position of the skeleton at the stern, instead lumping the discovery of all five timepieces together. These three deviations fall on a single page of McClintock’s book (p. 294, 1st ed.) — and without an intermediary like Parker Snow or a newspaper to pin the discrepancies on.

However disturbing to see apparent errors in McClintock’s narrative, it is simple enough to dismiss any deviations from Hobson on the grounds that McClintock wasn’t there. Most tellingly, McClintock presents neither evidence nor rationale for his identification of one skeleton as an officer — a stark omission.

Now with the addition of Edwards’ account, we can triangulate our evaluations of the other two narratives. Edwards told his story months before it was possible to purchase a copy of The Voyage of the Fox, and without access to Hobson’s official report to McClintock. Yet overall, his story bears out the details of Hobson’s account on a number of common points: Hobson, Toms, Edwards, and Christian were members of the sledging party. They departed the Fox on the 2nd of April. When they found it, the boat was almost entirely buried by snow, and had to be dug out. It was noticed by a pole sticking out from the snow. Something was found with one skeleton to suggest he was an officer. A mitt was found that had human remains inside it. The ship’s carpenter had been present at the moment of the discovery.

In all these details, Edwards confirms Hobson’s account. [And, Edwards names the two members of the sledging party omitted from Hobson’s report: Benjamin W. Pound and William Jones.]

In sum: Wherever McClintock’s narrative deviated from Hobson, Hobson’s version was more plausibly accurate. Now with the Edwards account, we have new deviations from Hobson to examine — and once again, Hobson’s version is the more plausibly accurate. Without ruling out that unique details from Edwards (or McClintock) may yet be proved correct, this new account further supports an evaluation of Hobson’s report as being the canonical version of events at the discovery of the Boat Place.

Not that Hobson’s surveillance of the excavation was perfect. As we have seen: Edwards managed to remove a book naming a lost officer from the site without Hobson detecting and intercepting it, keeping it out of The Voyage of the Fox until the 3rd edition.

Appendix 7: George Edwards biographical notes.

The HMS Assistance muster book entry for George Edwards (TNA ADM 38/7580) is dated 24 February 1852, and gives his age as 26 years and 1 month. It also says that his previous ships were HMS Firefly (1 Aug 1846 – 16 Oct 1847), HMS Powerful (16 April 1848 – 8 March 1851), and HMS Rodney (30 Aug 1851 – 23 Feb 1852).

Alison Freebairn also found a baptism certificate (DHC PE-WYK/RE/2/3) for a George Fry Edwards from Wyke, dated 11 February 1827, the son of William and Mary, profession listed as Carpenter.

A George Edwards shows up in the 1841 and 1851 censuses (aged 14 and 24) living in Wyke with William and Mary as well as several siblings (TNA HO107/286/19/5/4/829, HO107/1857/439/66/305).

Freebairn found a Carpenter’s Crew George Edwards from Wyke in the 1848 allotment book for HMS Powerful (TNA ADM 27/105/6), giving a mother’s name of Mary.

As well, a Seaman’s Ticket for a Carpenter’s Crew George Edwards from Wyke from May 1848 (TNA BT113/185, #369410) found by Freebairn seems to show a birthdate of either 22 January 1820 or 1826, with an age of 22. It states that he first went to sea as Carpenter’s Crew in the year 1846, has served in the Royal Navy 14 months, with this card issued from HMS Powerful on 22 May 1848. The card also states that Edwards could already write at this age.

The final service record for George Edwards of Wyke was found by DJ Holzhueter (TNA ADM 188/26), and states that he was “D.D. at Bombay” (Discharged Dead) on 1 November 1874. Much of this record is difficult to read, but it appears to list a birthdate for Edwards of 22 Jan 1829. His rating is listed either as Carpenter’s Crew or Carpenter’s Mate. His final ships in 1874 were HMS St. Vincent, Asia, Dasher, Asia, and finally Euphrates.

The death notice found by Holzhueter allowed Freebairn to find a burial record (BL IOR/N/3/48, page 295) for Edwards at Mumbai (Bombay) at Sewree Cemetery, which still exists. His profession is listed as Carpenter’s Crew. His cause of death is listed as Peritonitis, aged 48. He is listed as dying on 1st November 1874 and being buried on 2nd November 1874.

Appendix 8: Transcripts of the Edwards account.

Back’s account of interviewing Edwards, in The Nautical Magazine (January 1860).

Franklin’s Expedition: Another Relic.