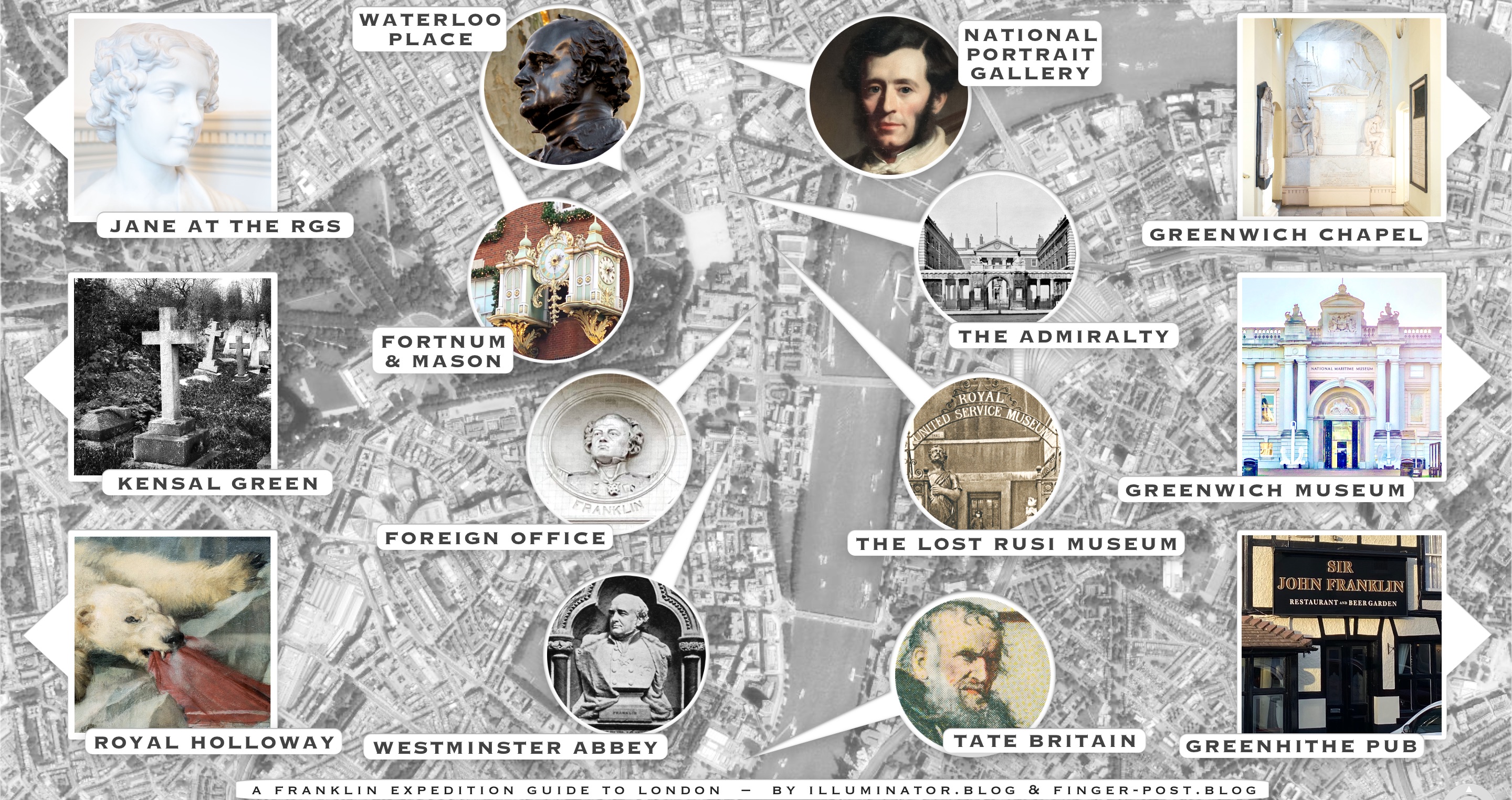

The Franklin Expedition vanished into the Northwest Passage almost 200 years ago. London was the city they departed from. Loved ones left behind were in London. The search to find them was directed from London. And, bits and pieces of the expedition have been returning to London ever since.

Thus London is home to more Franklin Expedition history sites than anywhere outside the Passage itself. This is a guide to touring them.

Don’t hesitate to browse the photographs before reading, as this guide is not ordered by importance. The initial sites listed are simply the ones within walking distance of Westminster Abbey, north to south (see map above). The guide then turns east towards Greenwich, then swings back west towards Kensal Green. Some of London’s best Franklin sites are out on these east/west fringes, requiring long tube and train rides to reach. Indeed the difficult site listed last here, the furthest from the center, will be the #1 priority for some travellers.

This guide is a project with ex-Londoner Alison Freebairn at Finger-Post.blog. This is our 3rd London/Franklin touring guide, connecting our previous guides to Greenwich’s Polar Worlds (link) and Kensal Green Cemetery (link). [And Alison has since completed a Franklin Expedition guide to touring Edinburgh (link).]

– L.Z. July 14, 2021.

* * *

{ Franklin at Waterloo Place. Author photo. }

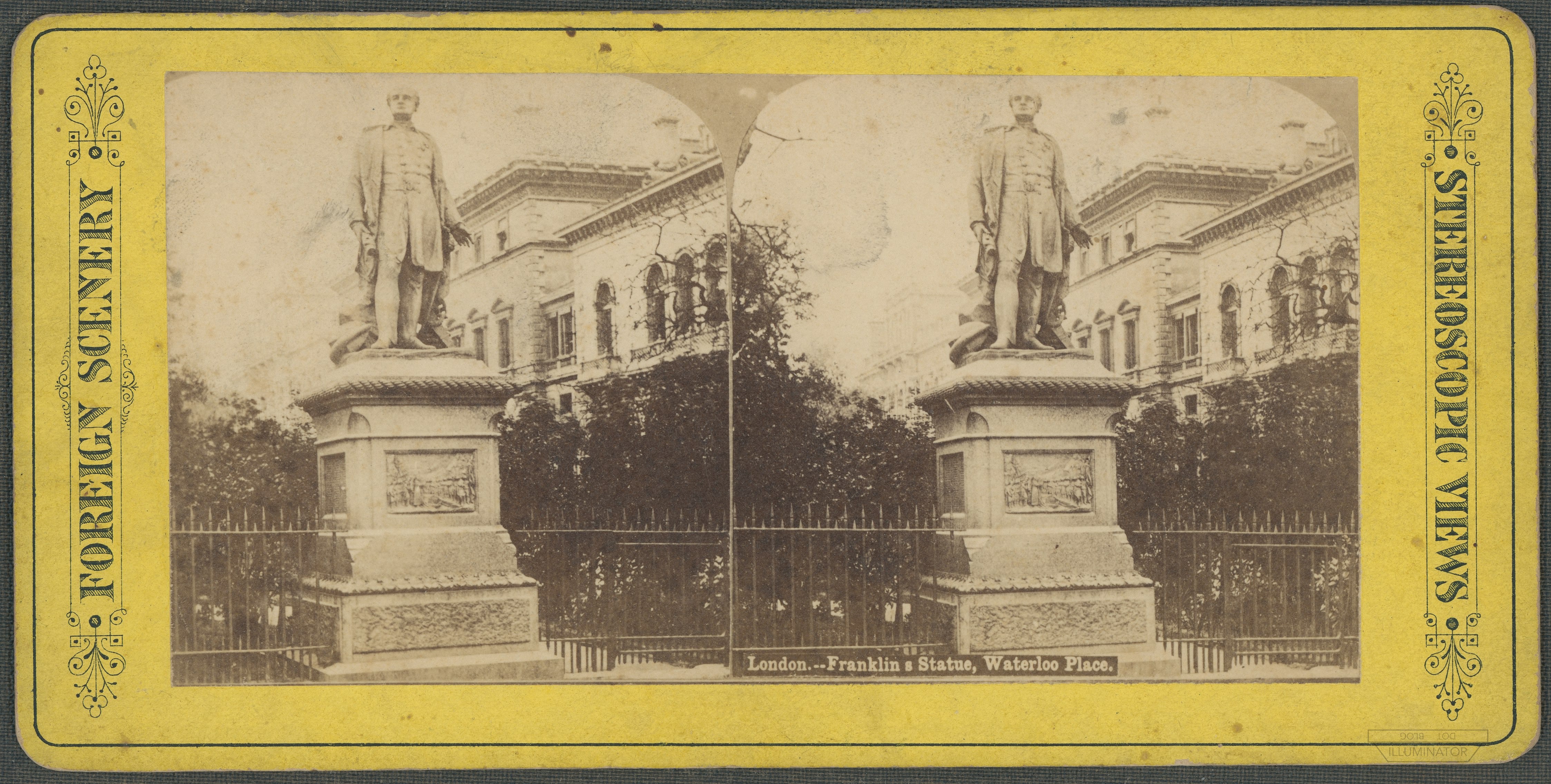

When this statue was unveiled before a crowd in 1866, Jane Franklin watched from the balcony of the Athenaeum Club next door. Intended as the primary London monument to the lost expedition, there had been a serious push to have it erected in Trafalgar Square. Here, Franklin stands almost directly across from a statue of Britain’s other polar martyr, Robert Falcon Scott. Waterloo Place is the easiest box to check off on a London Franklin tour, as you can visit the statue day or night.

But to see the hidden panel on the back, you’ll need the luck to catch a fence gate open during the day (or, a membership at the Athenaeum Club that controls this property). Each side of the granite pedestal features a bronze panel. On the left and right sides are full crew lists for Erebus and Terror. The hidden back panel features a map of the Arctic, showing two ships at the location known from the Victory Point Record.

{ Early stereogram; Athenaeum Club on the right. Author image. }

The Aberdeen granite pedestal is ringed above by a bronze cable, and below by oak leaves and acorns. On the pedestal’s front panel, a bearded Captain Crozier is reading the funeral service for the recently deceased Franklin. The casket lies on a sledge at his feet, with Franklin’s name and death date (June 11 1847) on the lid. In the background, Erebus and Terror are locked in the ice.

{ Franklin’s funeral. Photo by Andrés Paredes of Kabloonas (link). }

{ Used with permission. }

Atop the pedestal stands an 8 foot tall Sir John Franklin in bronze. He wears the three medals we see in his daguerreotype — including the one round his neck later traded to John Rae by the Inuit, today held in nearby Greenwich. A sword with a lion’s head pommel hangs from his belt; at his feet are a coiled cable and anchor hooked round blocks of ice. Franklin holds an octagonal telescope, charts, and caliper compass, as the sculptor is portraying Franklin’s announcement to the men that the southern sledge teams had completed the mapping of the Northwest Passage.

The statue was done by Matthew Noble in 1866. Nine years later, Noble would also create the bust of Franklin in Westminster Abbey.

{ McClintock by Stephen Pearce, eye detail. Author photo. }

{ McClintock by Stephen Pearce. Author photo. }

Update April 2025: Fabiënne Tetteroo spotted that a portrait of Sir John Ross by James Green (NPG 314) is now on display in Room 18. In May 2025, Alex Cross shared photos showing that it is the centerpiece of that room.

Update June 2023: Sadly, this first-rate London/Franklin site is no more. In the renovation of the gallery during the pandemic, all Northwest Passage-related portraits were removed.

Prior to the pandemic, the following significant portraits were on display here:

The Arctic Council by Stephen Pearce, 1851 (link).

Sir Leopold McClintock by Stephen Pearce, 1859 (link).

Sir Robert McClure by Stephen Pearce, 1855 (link).

Sir William Edward Parry by Samuel Drummond, ~1820 (link).

Sir James Clark Ross by Bernhard Smith, plaster medallion (link).

Sir John Richardson by Bernhard Smith, plaster medallion (link).

Early miniature of John Barrow (link).

Perhaps a future re-organization of the gallery will return some of these. Please contact me if you encounter any Franklin or Northwest Passage portrait on a future visit to the gallery.

{ McClintock by Stephen Pearce, glove detail. Author photo. }

[ Official website: NPG.org.uk ]

FORTNUM & MASON

More than a place for afternoon tea after a day of touring: Fortnum & Mason is the same firm, from this same address, that helped supply the Franklin Expedition in 1845.

Capt. Crozier growled at them, in one of the final letters sent home by the expedition:

“…my sugar and tea have not made their appearance. The sugar is a great loss to me but the tea I care not for. I cannot at all events say much for Fortnum and Mason’s punctuality. They directed my things to Captain Fitzjames Terror, but by some strange accident they discovered my name sufficiently accurate to send me the bill and I was fool enough to pay it from their declaring that the things were absolutely delivered on board. Growling again”

Letter to James Clark Ross (9 July 1845).

The name Fortnum & Mason also appears on one of the extremely rare surviving papers from the missing expedition: Beechey Paper #7, “Superior Chocolate Powder” (link), discovered on or near Beechey Island.

{ Beechey Paper #7. Photographed by author. }

{ The National Archives of the UK: ADM 7/190 }

The 2nd-to-last paragraph is of note. The emphasis on Parry (and the misspelling of the secondary Franklin) suggest that this product endorsement came during the 1820s Northwest Passage heyday. By the time the 1845 expedition was sailing, these past successes were older than some of Franklin’s crew.

The address written on this label – 182 Piccadilly – is still Fortnum & Mason’s address. (Note that Fortnum & Mason is a bit pricy, and that a reservation is needed ahead of time for afternoon tea.)

[ Official website: FortnumAndMason.com ]

THE ADMIRALTY

{ The Admiralty, circa 1895. Author image. }

The face of the Admiralty on Whitehall since the 18th century. Somewhere in this building, John Barrow sat at his desk. Later the Franklin search expeditions were planned and sent out from here.

It is not possible to enter, except under special circumstances such as the citywide Open House London festival weekend (and even then, this is apparently a difficult building to get into). However the Admiralty’s well-known facade (the Ripley building, seen above) can be viewed just by walking down Whitehall.

The location of Jane Franklin’s apartment, “The Battery,” is also nearby: 33 Spring Gardens, from where she fired off letters to the admirals at close range. But Jane’s apartment is long gone; the address is now the back entrance of a 1930s art deco theater (and it looks exactly like that sounds).

THE LOST RUSI MUSEUM

{ Banqueting Hall, once the RUSI Museum. Author image. }

Across the street from the Admiralty is the 17th century building which should have been the #1 site on this itinerary: the lost RUSI Museum, once the repository of the vast majority of London’s Franklin relics. The museum was liquidated in the 1960s to free up the Banqueting Hall building for Whitehall political receptions.

{ RUSI entrance – Orion and Bulldog figureheads. Author image. }

The RUSI Museum’s collection of Franklin relics went mostly to Greenwich, some were sold and have turned up in Calgary, and some are still missing. It’s now principally visited for being the site of King Charles’ execution, and for being a neoclassical Inigo Jones design with a Reubens ceiling. The RUSI as an institution still occupies the building next door, and their 1895 library is open by appointment.

Footnote 1: I have posted a few 1960s newspaper editorials, of horrified reactions unable to stop the museum’s dissolution and the auction of artifacts (link).

Footnote 2: Prior to 1895, the RUSI Museum’s location was just down the side street here, in a building nicknamed the Goose Pie House (click for image). When tens of thousands came to see the new blue Victory Point Record and other relics brought back by Captain McClintock, they were coming here. The Cheyne stereography of those relics was done at this location (link to article). The demolished museum building stood roughly where the Gurkha memorial statue is now (click for location image – the old RUSI is on the right, and you can see Horse Guards on the far distant left).

[ Official website: hrp.org.uk/Banqueting-House ]

FRANKLIN AT THE FOREIGN OFFICE

This Foreign Office building was constructed during the 1860s. Which means that Franklin’s bust was put here shortly after the McClintock relics went on display at the nearby RUSI Museum. If the sculptor had turned Franklin’s head in the other direction, he would have been looking up the street toward where the Victory Point Record then was.

Advisory: Due to the netting over the bust, if you take too close of a photograph, Franklin will look like he’s starring in a theater production of Hellraiser.

WESTMINSTER ABBEY

{ Source: Historic England Archive (link), 1875-1900 }

{ If zooming crashes your browser, just open that link. }

This monument was installed at the behest of Jane Franklin, on July 31st, 1875. While she saw it completed, she didn’t live to see it unveiled. She died on the 18th of that same month, and her funeral was in Kensal Green Cemetery on the 23rd – just a week before the unveiling.

The bust is by Matthew Noble, the same sculptor of the Waterloo Place statue a decade earlier. Noble again includes Franklin’s three medals seen in his daguerreotype, including the one recovered from the Arctic and held nearby in Greenwich.

{ Franklin spoon traded by the Inuit to John Rae. }

At the top is the Franklin family crest, a conger eel between two branches. This design will be familiar to Franklinists, as the same crest is seen on John’s spoons recovered from the Arctic. Below it is his family’s Latin motto NISV (“by struggle”), used on sledge flags during the McClintock search.

Lower down is a scene of two ships locked in the ice. At the bottom is the epitaph written for Franklin by the poet Alfred Tennyson (the husband of one of Franklin’s nieces):

Not here: the white north has thy bones; and thou, heroic sailor-soul, art passing on thine happier voyage now toward no earthly pole.

Beneath Franklin’s memorial are plaques for McClintock and Rae, the two searchers who zeroed in on where Franklin’s expedition had ended.

The monument is at a bottleneck in the crowd flow – which can make it easy to shuffle past unawares. Tickets must be purchased (online or in person) to enter the Abbey.

Footnote: Franklin descendant Mary Williamson has used her family’s papers to write two articles for Visions of the North on this monument, adding a number of personal details around the unveiling ceremony (1st article link) (2nd article link).

[ Official website: Westminster-Abbey.org ]

THE NORTH-WEST PASSAGE AT TATE BRITAIN

{ The North-West Passage by John Everett Millais. 1874. Tate. }

John Everett Millais composed this painting in 1874, during the preparations for the first major British Arctic expedition since Franklin’s thirty years earlier. The age of the graying sailor shows that he is a veteran of either the Franklin searches or earlier Northwest Passage attempts.

Above all, the look on the face of the sailor makes this painting remarkable. The search for the passage is not idealized; the hardship, regret, and failure of the previous generation are all conveyed in his eyes. He has a glass of alcohol by him, as a young girl’s index finger goes through a journal or history of the search. That younger generation’s hand is atop the older man’s clenched hand, which is to say: she is encouraging him through this moment, not the other way round. Millais’ subtitle for exhibition, “It might be done and England should do it,” seems a band-aid on how conflicted this painting reads.

The map on the table is the Inglefield chart of HMS Investigator’s Northwest Passage discovery, during their Franklin search (that passage had to be completed on foot across ice, the ship was abandoned, men died, etc). On the wall are hung depictions of Admiral Nelson and a ship locked in the ice.

Unfortunately Tate Britain has this painting hung very high. I’ve licensed the above high resolution image from the Tate so that fine details can be studied before a visit is made in person. Update May 2023: Millais’ painting is now hung at eye level; see photographs here (link).

Footnote: The expedition then under preparation in 1874 would be Nares 1875-76 attempt at the North Pole. Polar Worlds in Greenwich currently has relics from this expedition on display.

Further reading: ‘The North-West Passage’ by Sir John Millais by Ian R. Stone (link).

* * *

– POINTS EAST –

GREENWICH MUSEUM

GREENWICH CHAPEL

BELLOT’S OBELISK

GREENHITHE PUB

* * *

GREENWICH NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM

{ Greenwich museum, Neptune Hall entrance. }

The home of the lion’s share of all Franklin relics – a title that can only be taken away if Canada finishes excavating Erebus and Terror. Nearly every famous Franklin relic from the Victorian search era is held here, including the Victory Point Record (too fragile for public display).

However only a very few Franklin relics are on display at one time. The current Polar Worlds exhibit is showing about a dozen, plus many other artifacts related to Franklin and the Northwest Passage – and paintings of Erebus and Terror. I’ve written a dedicated Franklin guide to the Polar Worlds exhibit (link).

Greenwich’s museum is also the only Franklin site in London where elements of Inuit culture can be seen. The final cabinet in Polar Worlds displays a fusion of artifacts, pieces of Erebus & Terror that the Inuit transformed into tools for Arctic survival – e.g. literally a Goldner can made into an ulu. There is an instructional video by Sammy Kogvik, the Inuk from Gjoa Haven who in 2016 directed searchers to Terror Bay.

When you are here, you are extremely close to two other Franklin sites (discussed next): the grave of an actual Franklin Expedition sailor at the Old Royal Naval College, and the Bellot monument on the Thames waterfront. There’s also a large public park behind the museum which leads to the Royal Observatory – and beyond that, to a house stayed in by James Clark Ross and Francis Crozier (see Homes section in the Appendix). Somewhere beneath the yard to the west is where William Edward Parry is buried, and there’s a monument nearby listing his name (see photo below). Many historical documents can also be requested at the museum’s Caird Library. Entry to the museum is free.

What is this collection of buildings?

The museum complex is essentially a mini-palace with a sailors’ orphanage built around it. The august Victorian facade was in fact the boys’ gymnasium.

{ The museum vs. the college. Author image & notations. }

The National Maritime Museum occupies a number of buildings further back from the river than Wren’s Old Royal Naval College (née Greenwich Hospital). The central building – the Queen’s House – is by far the oldest, built in the early 1600s as part of the palace then sitting on Wren’s future Hospital site. During the Napoleonic Wars, that Queen’s House was donated to the Hospital’s school for sailors’ orphans. As part of this transition, east and west wings were erected and attached via long colonnade arms, as we see today. Half a century after these (in the years between the McClintock and Schwatka searches), a 2nd L-shaped western wing was added, and between this new western wing and the older western wing was dropped a gymnasium: Neptune’s Hall. The facade of that old gymnasium for the boys’ school is now the main entrance to the National Maritime Museum (and this history explains why the entrance’s bookend wings are mismatched). The school/orphanage was known as, "the cradle of the Royal Navy.”

After the Franklin Expedition disappeared, the sons of four missing Franklin Expedition fathers – William Wentzell, Richard Wall, Alexander Wilson, and Robert Johns – were sent to live here. Cyriax states that the Erebus’ Second Master Henry Foster Collins had been educated here as well. In addition, Parker Snow (eccentric Franklin searcher) and Ernest Joyce (Shackleton Ross Sea Party leader) had been sent here after their fathers died.

{ Fame on the Queen’s House lawn. Author image. }

Above is a photograph of the Queen’s House when it was still functioning as a boys’ school. A training ship, “Fame,” is visible where today there is only grass. When the Queen’s House became a maritime museum, her three-masted lawn ornament was destroyed (the Fame’s bare-breasted figurehead still exists, as the schoolboys marched off with her when they relocated to Suffolk). Given this historical precedent, I believe another wooden-hulled ship will one day be placed before the Queen’s House. I suggest that she should be an exact replica of HMS Terror. Terror is certainly famous, but more importantly: we will soon know every last deck plank, propeller blade, cabin bunk, and captain’s chair of her, down to the last illuminator. Terror’s icy grave preserves her like a Beechey Island mummy, but it also keeps her too remote to be recovered by Canada. As eye-catching as Fame was on the Queen’s House lawn, so too would be a new HMS Terror for London.

[ Official website: RMG.co.uk ]

GREENWICH HOSPITAL’S CHAPEL

{ Franklin monument, globe marked "British America." }

{ Old Royal Naval College Chapel. Author photo. }

While there are many graves in London related to Franklin and the Northwest Passage, there is only one place in London to visit the grave of an actual sailor from the Franklin Expedition: the Chapel of Greenwich Hospital (now known as the Old Royal Naval College). The bones are believed to be Harry Goodsir, the naturalist and Assistant Surgeon aboard HMS Erebus.

{ 1858 Franklin monument. Note the Pole Star detail near the top. }

{ Author photograph. }

In 1869, the Inuit led Franklin searcher Charles Francis Hall to this skeleton on King William Island, found along with the remains of a silk vest. Hall brought the bones back to the United States, where they found their way to the Royal Navy’s attaché in Washington DC: Edward Inglefield, himself a veteran Franklin searcher.

{ London’s only Franklin Expedition grave. Author photo. }

Inglefield returned the skeleton to England. An analysis at the time decided that these were the bones of Lieutenant Le Vesconte from HMS Erebus. In 1873, the skeleton was interred beneath the pavement before the Franklin Expedition monument at Greenwich Hospital. The Hospital’s Franklin Expedition monument already existed, finished in 1858. (This seems odd given that McClintock was still out searching, but the plan was enacted after Rae’s discoveries proved that Franklin at least was dead.) The monument was not built for the Chapel; its original position was in the Painted Hall – home to the Franklin relics brought back by Rae.

{ Greenwich Chapel narthex, Franklin monument in alcove. }

During renovations in 1938, both monument and skeleton were transferred from beneath one of Wren’s domes to the other: from the Painted Hall to the Chapel. They were unfortunately relegated to a stairwell; only in 2009 were monument and sailor’s skeleton placed prominently in the Chapel narthex, as seen today. That final 2009 transferral had an additional benefit: it was an opportunity for a modern re-examination of the bones, which in 2011 changed the original identification away from Le Vesconte. The new study used details about the teeth to infer that in fact the skeleton is likely to be Harry Goodsir (link to paper).

The Chapel has one other connection to the Franklin Expedition: a wooden memorial plaque naming Edwin James Howard Helpman, the 23 year old Clerk in Charge on HMS Terror. He had previously served under Fitzjames on the Clio. He is here memorialized as one of the, “Old Boys of the Royal Naval School who died in the service of their Country.” [Note: this school was neither the orphanage nor the college; it was a school for officers’ sons that moved near Greenwich in 1844.]

{ Photograph by Alison Freebairn. }

{ The Old Royal Naval College from the Thames. Author image. }

What is this collection of buildings?

The Old Royal Naval College is one of the architectural landmarks of London. It was designed by Christopher Wren as Greenwich Hospital at the start of the 1700s. In this instance, the meaning of “hospital” is closer to hospitality; it was a home for aged Royal Navy sailors. In 1873, Greenwich Hospital became the new Royal Naval College (coincidentally or not, the same year that the skeleton was interred in the Painted Hall). The Royal Naval College left the premises in 1998; it is now mostly occupied by the University of Greenwich, however the site retains the former college’s name.

Prior to Greenwich Hospital, this property had been a royal palace (the birthplace of Henry VIII, Mary I, and Elizabeth I), of which the Queen’s House was a late addition. The four “courts” or buildings are split to allow the Queen’s House behind them to view the Thames (their split being the width of the Queen’s House).

Further reading: ‘Nelsons of Discovery’: Notes on the Franklin Monument in Greenwich by Huw Lewis-Jones (link).

[ Official website: ORNC.org ]

BELLOT’S OBELISK

{ The Bellot Memorial at Greenwich Hospital (link) 1857 }

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London }

In old sketches and photographs of Beechey Island, there are not three grave markers: there are five. If only three Franklin Expedition sailors died on Beechey, then whose were the other two graves? One was for Joseph René Bellot, for whom this obelisk in Greenwich stands. Bellot was a French naval officer, yet he volunteered for two Franklin searches. On the first, Bellot helped the Royal Navy add to their maps the critical strait that connects Prince Regent Inlet west to Peel Sound, now bearing his name: Bellot Strait. But Bellot is not buried on Beechey; his body lies at the bottom of Wellington Channel to the northwest. He died falling through the ice in August 1853, on a mission during the Belcher search. Greenwich’s monument to Bellot was dedicated in 1856, and is made of Aberdeen granite (like Franklin’s pedestal on Waterloo Place a decade later). When Beechey Island’s historic grave markers were replaced with replicas in recent decades, for some reason a marker for Joseph René Bellot was not replaced – and never has been.

Footnote 1: For more information on Bellot, see the 20 min. video (link) by Nadine & Jean-Claude Forestier-Blazart. As a bonus, in the first two minutes is an image of the Greenwich Chapel memorial in its old (pre-2009) back stairwell location. These two creators co-authored with William Barr the 2014 Polar Record paper on Bellot (link). Frances Woodward also wrote a paper on Bellot for Polar Record in 1950 (link).

Footnote 2: The fifth grave marker on Beechey is for Thomas Morgan, a sailor from McClure’s HMS Investigator who died during their Northwest Passage crossing/Franklin search.

GREENHITHE PUB

{ The Sir John Franklin Pub in Greenhithe. }

Every person you’ve read about in this story, every Fitzjames anecdote about someone that’s stuck in your head, a family’s crest that you know from a spoon, Victorian handwriting you’ve struggled through, caulker’s mate who carved his name into a knife handle, seaman clutching his certificate case: they were all right here. Everyone in this story was at this spot, and they were all here together. Jane Franklin was among them, the final peaceful year of her life before she became The Search personified. Sophia Cracroft was here, the last time Crozier would see her. Torrington, Braine, and Hartnell were up walking around. Two Antarctic veterans were visible over the top of the pub: sister bomb ships that would require underwater multibeam sonar in the dark to ever find again. The Beard daguerreotypist came onboard Erebus and took his daguerreotypes here; those reflections in Graham Gore’s cap brim are of this place. An artist from the Illustrated London News was in Fitzjames’ cabin, sketching that there were two portraits on his wall. The sound of fiddle music and Neptune barking was coming from Erebus. Marines in red were getting a drink together, and lieutenant’s epaulettes were turning villagers’ heads as they jingled along the high street.

And in addition to all these people we know, crowds of Londoners were jammed into the village for the May 19th departure. The newspaper sketch showed additional onlookers out in boats, gawking and pointing at Erebus and Terror as they set sail. Osmer on Erebus wrote that the cheering of the crowds here as they left was “deafening.”

This is the Sir John Franklin Pub (then the White Hart) and its quay, in the quiet village of Greenhithe on the Thames. A train to Greenhithe station puts you within a five minutes walk to the site. The pub today caters to locals getting off work, with only a few decorative nods to 1845. You can get a beer here, but you might be just as content to take the road to the left and look out on the water for a bit.

After they left and vanished, search teams above the Arctic Circle would find a two-gallon earthenware jug from the expedition. It was marked, “R. Wheatley, Wine and Spirit Merchant, Greenhithe, Kent.”

Footnote 1: The 1850-51 Royal Navy search squadron also left from Greenhithe. Then McClintock was here, and Sherard Osborn, Captains Austin and Ommanney, and the young Clements Markham. They sailed from here in April; that August they would find a rake at Cape Riley, then a cairn across the bay, and finally three graves on that same island – Beechey.

Footnote 2: Franklin researcher Peter Carney of Erebus & Terror Files (link) was filmed here visiting the Sir John Franklin Pub and speaking about the expedition. The brief two minute video is an excellent visual overview of the scene.

{ Peter Carney at Greenhithe. Direct link to open in new tab/app. }

(The other two of the three videos in this series show Peter at St. Andrews church in Gravesend. See the Minor Sites section in the Appendix for more information.)

Footnote 3: Dover-Kent.com has a number of older images and photography of the pub waterfront and exterior (link). (Note that there used to be a Catholic church immediately left/west of the pub.)

Footnote 4: The Greenhithe wine jug was found by Schwatka’s American search expedition, 1879, on King William Island.

Footnote 5: London also has an Enterprise pub, with a mosaic of the ship sailing in icy waters near a polar bear. To find this pub, see our article about this and other (lost) Franklin Expedition pubs of London (link).

* * *

– POINTS WEST –

JANE AT THE RGS

KENSAL GREEN CEMETERY

McCLINTOCK’S CEMETERY

THE LANDSEER AT ROYAL HOLLOWAY

* * *

JANE FRANKLIN AT THE RGS

{ Jane Franklin by Mary Grant, 1877. Author photograph. }

Before her death, Jane Franklin lobbied to have her husband memorialized in stone at Westminster Abbey and Waterloo Place. Yet the only sculpture of Jane herself in London is this marble bust, created after she had passed away. It was based on the portrait of her at age 23 by Amélie Romilly in Geneva.

{ The Royal Geographical Society, London. }

Held by the Royal Geographical Society, this unique sculpture is immediately inside a building that is unfortunately not open to the public. One recent Franklin writer managed to talk his way past security for a brief visit, however another writer (not a mother tongue English speaker) was refused access. The bust of Jane is in a hall immediately inside the main entrance, to your left as you walk in. You can nearly see her through the front windows, deep in the corner at the ground floor.

Good luck trying – it doesn’t hurt to ask. The entrance guards are not responsible for this policy, and being a door guard in a massive city is apt to make one grouchy. Mention that the statue is just inside to the left, and you’d only be just a minute. When they gruffly respond that the building is not open to the public, one might try flashing some history at them, such as that Jane received their Founder’s Medal – the first woman they ever awarded a society medal to – in 1860, in the wake of McClintock’s discoveries in the Fox, which she had financed, even after the Admiralty had given up, etc etc. Do send me a message about how it goes for you.

Footnote: I have a page with more photographs of the bust (link). Alison has written about the Romilly portrait on which this bust is based (link).

[Official website: RGS.org ]

KENSAL GREEN CEMETERY

{ John Ross at Kensal Green Cemetery. Author photo. }

A few miles northwest from Buckingham Palace is a massive Victorian cemetery of sinking graves and tilting monuments. It is London’s titanic Kensal Green Cemetery. It contains more grave monuments relating to the Franklin Expedition and the Northwest Passage than anywhere else.

Buried here are Jane Franklin, Sophia Cracroft, John Ross, John Barrow Jr, George Back, Robert McClure, Clements Markham, and more.

For a full list of Northwest Passage graves at Kensal Green – and a map of their locations – Alison Freebairn and I have written a dedicated guide (link).

[ Official website: KensalGreenCemetery.com ]

McCLINTOCK AT HANWELL CEMETERY

{ Hanwell cemetery. The tallest cross is McClintock’s. }

There seems to be just one grave at this cemetery related to the Franklin story, but it’s one that justifies the journey: Francis Leopold McClintock, leader of the expedition that recovered the Victory Point Record. He lies under a Celtic cross just off the back corner of the old church. McClintock is buried with his wife Annette Elizabeth McClintock, née Delap, who wrote a pamphlet about the Franklin relics for the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition.

Footnote: Hanwell’s historic name is the City of Westminster Cemetery. There’s an odd polar detail you may run into during your visit: the graveyard is frequented by an extremely friendly big grey cat whose name-tag reads Mrs. Chippy (same as the ship’s cat on Shackleton’s 1914-17 expedition).

THE LANDSEER AT ROYAL HOLLOWAY

{ Man Proposes, God Disposes by Edwin Landseer, 1864. }

{ Author photograph. }

The furthest site west on the map is also the most difficult. Edwin Landseer’s Man Proposes, God Disposes hangs in the picture gallery of Royal Holloway, founded as a Victorian school for girls. Landseer painted this masterpiece in 1864, in the wake of the McClintock expedition’s discovery of the Victory Point Record and the Boat Place. The painting’s scene of nautical ruin and bones being devoured by joyous polar bears was enough to earn a public snub from Jane Franklin. Royal Holloway tradition continues to cover up the painting beneath a Union Jack whenever students are seated here for testing.

{ Royal Holloway. Author photo. }

A good deal of planning in advance is necessary to visit this Franklin site. Royal Holloway’s picture gallery is open just one day per week (“It’s a Wednesday, sir.”), only for a few hours, and only during the school year. The journey via train from London may take an hour or two. From the nearest train station (Egham), it’s still necessary to call a cab or find the right bus – or, to walk briskly out of town for a solid half an hour.

{ Royal Holloway’s Picture Gallery; the Landseer is on the left. }

Plan to give yourself additional time here. The rest of Royal Holloway’s picture collection, though contained in just one room, deserves hours of viewing time. In addition to the stunning exterior architecture, there is also an interesting Victorian chapel opposite the Picture Gallery.

Further reading: Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818-1875 by Russell A. Potter.

[ Official website: RoyalHolloway.ac.uk ]

* * *

– APPENDIX –

HOMES

GRAVES NOT IN KENSAL GREEN

ADDITIONAL SITES

FURTHER AFIELD

ADDITIONAL NOTES

CONTRIBUTIONS

* * *

HOMES

James Clark Ross: 2 Eliot Place, Blackheath (maps link). Before sailing away in 1845, Crozier stayed here with his friend and Antarctic superior officer, James Clark Ross. Alexa Price alerted me that Crozier disliked the house, calling it "comfortless" and "Bleakheath" [sic!] – but not ungraciously, evidently in agreement with the Rosses that they needed better lodgings for their family. A blue plaque marks the house.

Jane Franklin’s "The Battery": 33 Spring Gardens (maps link). Now the back entrance of a 1930s art deco theater. Alexa Price directed me to a letter Jane wrote from here to James Clark Ross (Dec 8 1849), denying that she had moved here to pressure the admirals, and then two sentences later remarking that the admirals will do nothing unless someone pressures them.

Jane Franklin’s Griffin family home: 21 Bedford Place (maps link).

Jane & Sophia’s final home: 45 Phillimore Gardens (maps link).

John Rae’s final home: 4 Lower Addison Gardens, Holland Park (maps link). A blue plaque marks the house.

GRAVES NOT IN KENSAL GREEN

A memorial for John Smart Peddie, Surgeon on HMS Terror, is added to the grave of his daughter, Annie Eliza, in the churchyard of St Luke’s Church in Charlton, near Greenwich. The gravestone is flat on the ground and its inscription is vanishing. It reads, “Also in memory of John Smart Peddie, Esq., father of the above, Surgeon HMS Terror, who perished in the Polar Regions in the Expedition under Capt. John Franklin.” The gravestone is currently directly beneath a park bench (to the right as you approach the church). (Link to Kabloonas article.)

The grave of William Edward Parry is in Greenwich, somewhere under the ground off the westernmost wing of the National Maritime Museum. The entrance to the vault is sealed, and the plaque there commemorating Parry was blown away by Nazis during the Blitz. Parry’s name is however mentioned on a nearby officer’s monument (see the aerial photo in the Greenwich Museum section). Parry is also commemorated by a plaque at Holy Trinity Church in Tunbridge Wells, along with a plaque and the grave of his first wife, Isabella Louisa, and their two sons who died with her there in childbirth. The grave is in the yard behind the church, but their two plaques inside the church require permission in advance to view.

The grave of Erasmus Ommanney, Captain of HMS Assistance on the 1850-51 Franklin search, is close to the National Archives in Kew. He discovered the first traces at Cape Riley, which led to the discovery of the Beechey Island graves a few days later. Alison at Finger-Post.blog has written an article about finding his grave (link).

The grave of John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty, is in Camden. Barrow’s personal obsession with finding the Northwest Passage was a driving force behind the 19th century Royal Navy expeditions. He was buried at St. Martin’s Cemetery in Camden, but Alison and I could find no clear evidence of his grave surviving there (the cemetery was mostly converted into a park). Please contact us if you know more.

The grave of James Clark Ross (link to photographs) is northwest of London in Aston Abbots, in the churchyard of St. James the Great (an easy name to remember in this context). His wife Ann and daughter Anne are buried there as well. A window in the church has an inscription commemorating James and Ann.

The grave of Franklin searcher William Parker Snow is in Bexleyheath Cemetery just east of Greenwich. Snow and his wife Sarah are in an unmarked grave near the southeast corner (link to photograph).

ADDITIONAL SITES

The brick church ruin at Stanmore was the site of John and Jane Franklin’s wedding, on November 5th 1828. Karin Lach connected this ruin to Franklin history after reading in Ken McGoogan’s Lady Franklin’s Revenge that Jane revisited her Stanmore wedding church (then slated to be demolished) on the day that Eleanor married John Philip Gell. The demolition was evidently cancelled when half-complete due to a public outcry. The ruin interior can be visited from April to September.

The East India Docks Basin is where McClintock’s ship the Fox docked after returning from the Northwest Passage with the Victory Point Record. Here she was photographed by John Powles Cheyne for his stereoscopic slides of the Franklin relics. I wrote about tracking down this location for my series on Cheyne (link). Nearby, Alison Freebairn and I found that from 1859 there had been a Sir John Franklin public house here, presumably memorializing the Fox’s return (link).

St. Andrew’s Church in Gravesend has a plaque to the lost expedition presented by Jane Franklin, seen in the visit by Peter Carney (link1, link2). Peter also wrote about the plaque in 2012 (link). Three windows there were also presented by Jane. Cyriax mentions the site in Appendix 1 of his book.

John Franklin was one of the founders of St. Paul’s Church on Dock Street. There is a memorial window there to him from 1873. The church now functions as a nursery, thus permission to visit would require some arranging. Cyriax mentions the site in Appendix 1 of his book.

George Hodgson (Lieutenant on HMS Terror) was baptized at St. George’s Church at Hanover Square in 1817, when his family was living nearby at 15 Grosvenor Street. These sites were found by Hattie (@fadladinida), who the same day visited St. Marylebone Parish Church. That church contains elements of the previous parish church; the vicar believed one to be the baptismal font, which may make it the font at which James Fitzjames and Thomas Jopson were baptized, in 1815 and 1816 respectively. (The site of that previous church is now the nearby Garden of Rest.)

The Linnean Society has the same James Clark Ross and John Richardson roundels that are at the National Portrait Gallery. Their curator Glenn Benson has written an article about these (link).

FURTHER AFIELD

Cambridge has the Scott Polar Research Institute, only a short walk from the train station. The public museum of the institute has some of their Franklin relics on display. By far the most notable is slightly hidden in a protective drawer beneath the others: the Gore Point Record. The sibling to the more famous Victory Point Record, the GPR has the VPR’s same 1847 message, but lacks the 1848 message around the edges. Cambridge is about an hour away from London by train, so if you’re considering Greenhithe and Royal Holloway, Cambridge is comparable travel time.

Spilsby is the hometown of John Franklin. There is an 1861 statue of him on the high street, a memorial plaque in St. James Church, and a plaque marking the home where he was born.

Edinburgh has something only London and the Arctic can claim: the grave of a Franklin Expedition sailor. Buried in Dean Cemetery under an impressive monument, the skeleton was recovered by the Schwatka search. Based on a medal found outside the grave, he has been identified as John Irving from HMS Terror. I have a page with photographs from my visit (link). As well, Alison Freebairn has written an entire guide to touring the Franklin Expedition in Edinburgh (link).

{ Edward Inglefield in full regalia. }

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London }

Note 1: Franklin searcher Edward Inglefield makes several cameo appearances throughout this guide. At Greenwich Chapel, it was he who brought the Goodsir skeleton home from North America to Britain. At Tate Britain, it was he who drew the original of the Northwest Passage map seen on the table in Millais’ painting. In Greenwich museum, the “1852-3” Goldner can in Polar Worlds was brought back from Beechey Island by him. And at Kensal Green Cemetery, he’s one of the Northwest Passage graves that can be visited. Inglefield was also notably present at the 1852 autopsy of John Hartnell on Beechey Island. He absconded with Hartnell’s coffin plate – and it’s never been seen again.

Note 2: Both the Queen’s House and Banqueting Hall (ex-RUSI Museum) on this list were the first neo-classical buildings built in Britain, both in the early 1600s by Inigo Jones after a trip to Italy.

CONTRIBUTIONS

Thanks to Alexa Price (link) for sharing her knowledge on Crozier, James Clark Ross, the Blackheath home, and Jane Franklin at Spring Gardens.

Thanks to Andrés Paredes (link to Kabloonas blog) for use of his blog’s trademark image of the Waterloo Place funeral relief.

Thanks to Hyge Burg for her research which uncovered that the sons of William Wentzell and Richard Wall were sent to Greenwich’s Royal Hospital School after their fathers disappeared with the 1845 expedition.

Thanks to William A. Greenwell for spotting the Helpman memorial in Greenwich Hospital Chapel in 2015 and writing about it (link).

Thanks to Roxana Cioruta for noting that the Arctic Council had gone up at the National Portrait Gallery after my visit.

Thanks to Regina Koellner, whose London photographs in years past I studied to prepare my own London-Franklin tour.

Thanks to Wolfgang Opel (link to Trimaris blog) for spotting that I had missed John Rae’s home at Holland Park.

Thanks to Karin Lach who discovered (link) that the church where John and Jane Franklin were married, though half-demolished, still survives in Stanmore.

Thanks to Kevin Paul McKenzie whose research into his family history showed that Robert Johns’ son was one of the sons of missing Franklin Expedition fathers sent to Greenwich Hospital School.

Thanks to Hattie (@fadladinida) for finding the church where George Hodgson was baptized and other sites near Hanover Square.

The End.

– L.Z. July 14, 2021.