By Logan Zachary. November 20, 2022.

Summary: Multiple photographs of the 1891 Franklin Gallery are assembled to simulate a walk-through. A floor plan of the gallery is created. The Victory Point Record is identified. An artifact without provenance at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum is identified.

Acknowledgments:

Douglas Wamsley

Sylvia Wright

Russell Potter

Alexa Price

Glenn Marty Stein

Allegra Rosenberg

Jeremy Michell

Claire Warrior

Frank Michael Schuster

Andrés Paredes

Brent Piniuta

Richard Crangle

Kenn Harper

& Alison Freebairn

Previously this blog has debuted three guides to touring the Franklin Expedition in London. This guide will be the fourth, and is again set in London. However, this site cannot be visited without a time machine.

When I was trying to convince my fellow Midwesterners to travel to the Franklin relics exhibition Death In The Ice, I would remark that “…there hasn’t been one of these since 1891.” That 1891 exhibition was London’s massive Royal Naval Exhibition, of which the Franklin Expedition represented just one slice — the first gallery upon entering the gates.

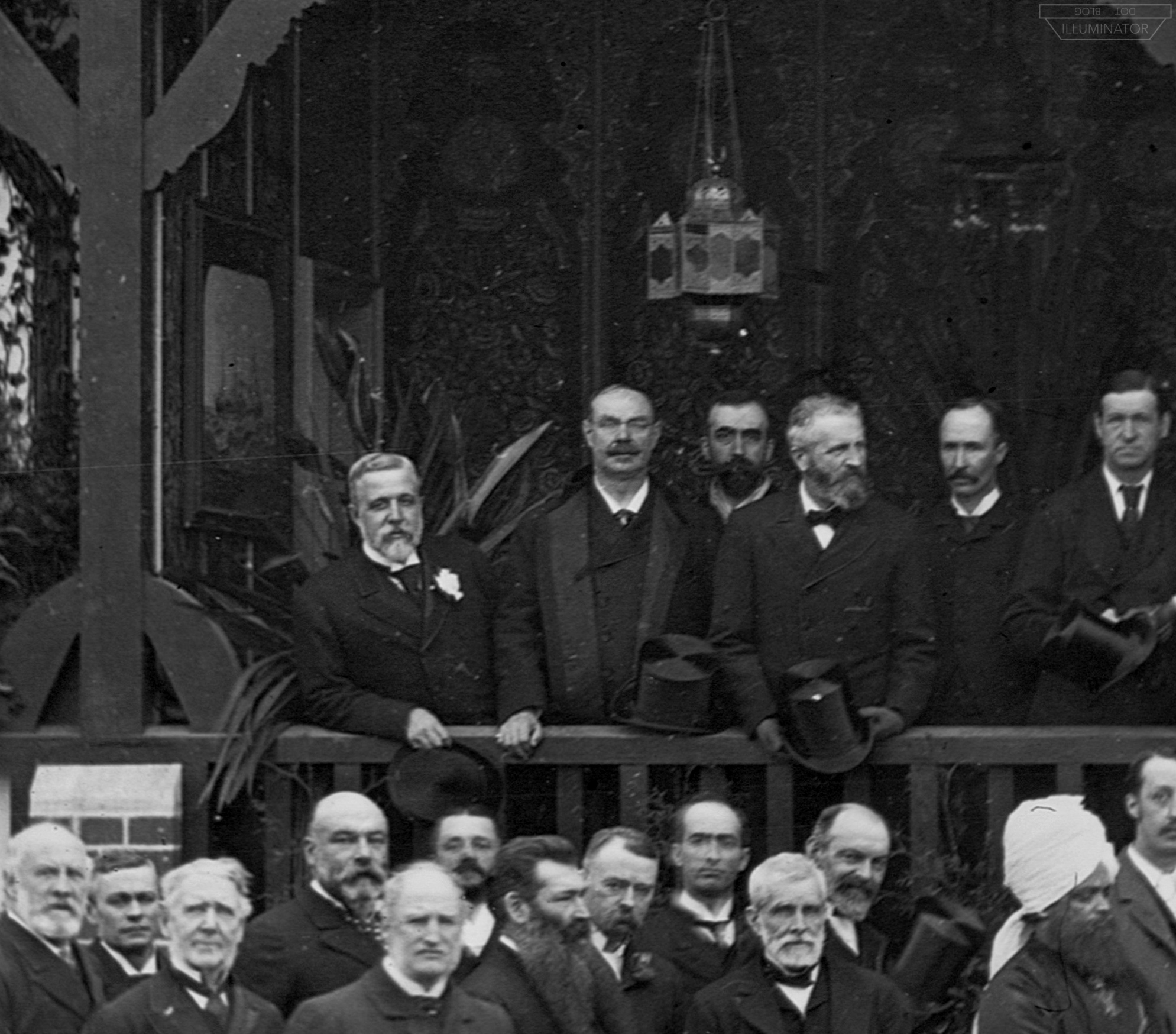

{ ▽ The Royal Naval Exhibition. Penny Illustrated, 2 May 1891. }

{ ▽ The Royal Naval Exhibition. ILN, 6 June 1891. }

{ ▽ Londoners ogle mannequins on an Arctic expedition. }

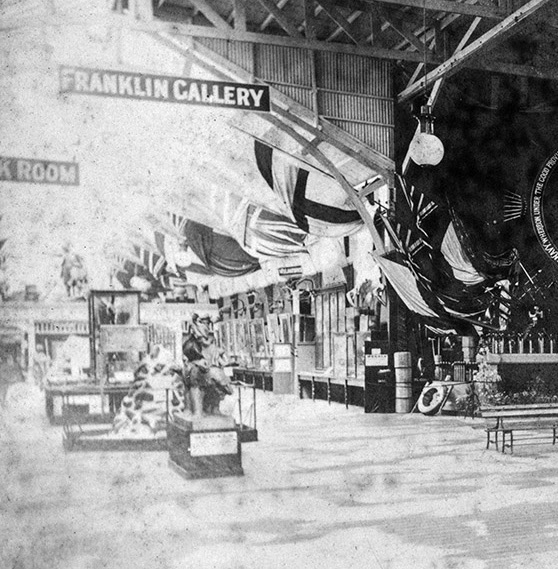

{ The Franklin Gallery in The Graphic, 9 May 1891. }

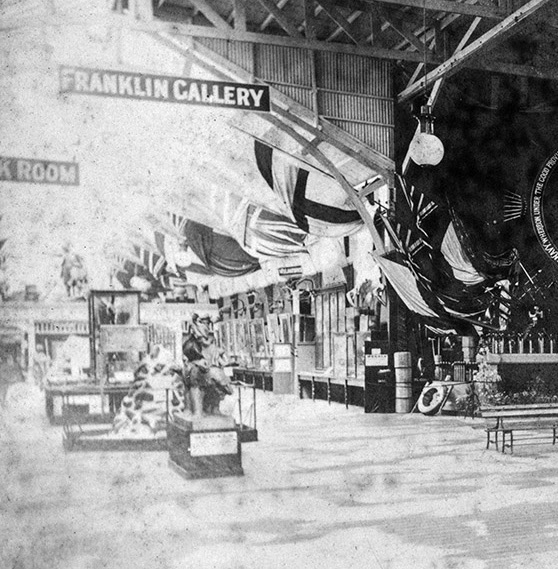

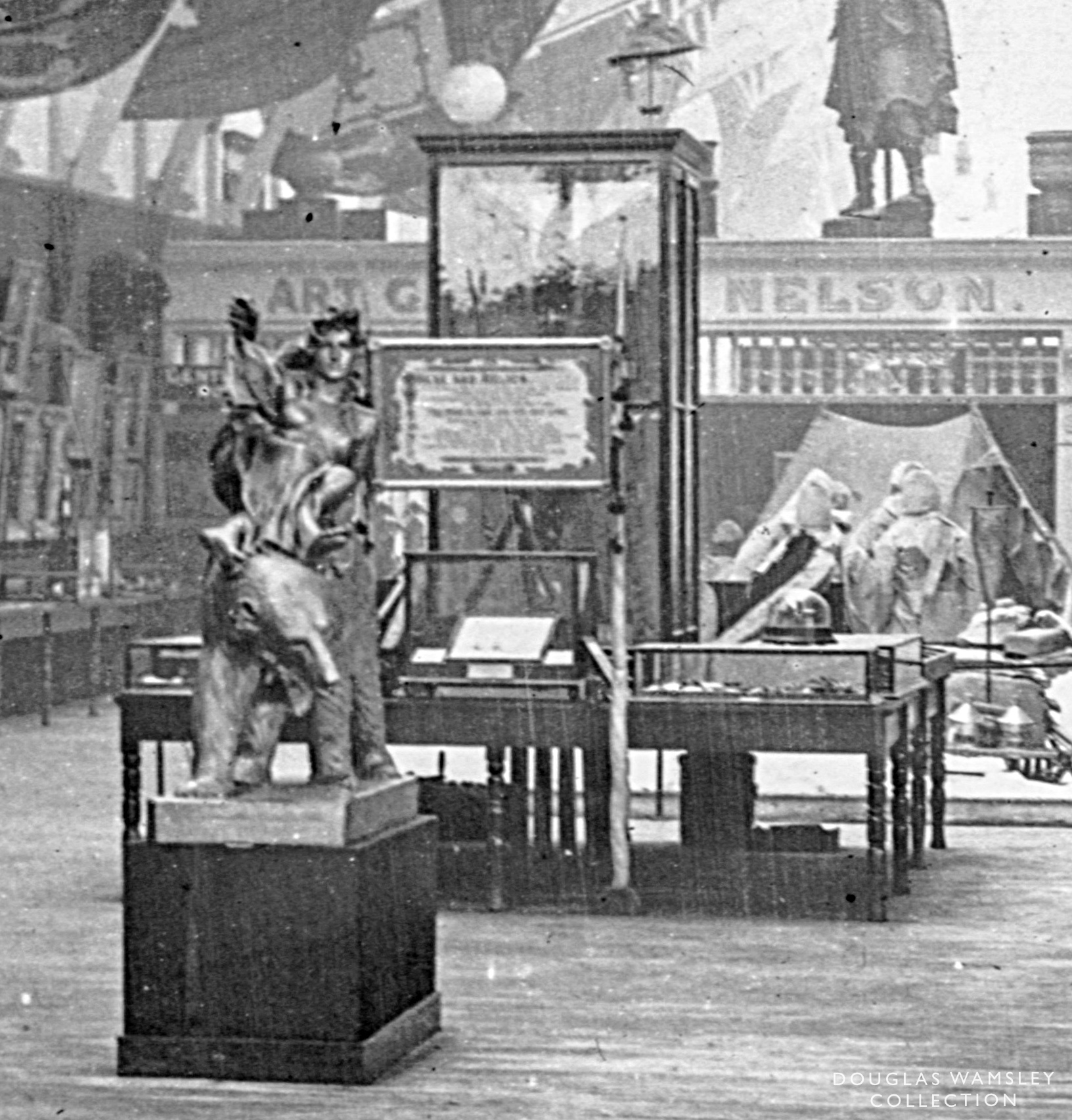

A photograph has survived of the “Franklin Gallery” at the Royal Naval Exhibition. If you’ve read Huw Lewis-Jones’ paper devoted to the Franklin Gallery (2005), or have seen Russell Potter’s talk “Relics of Surpassing Interest” (2018), you may recall seeing that one photograph.

{ Russell Potter in “Relics of Surpassing Interest.” }

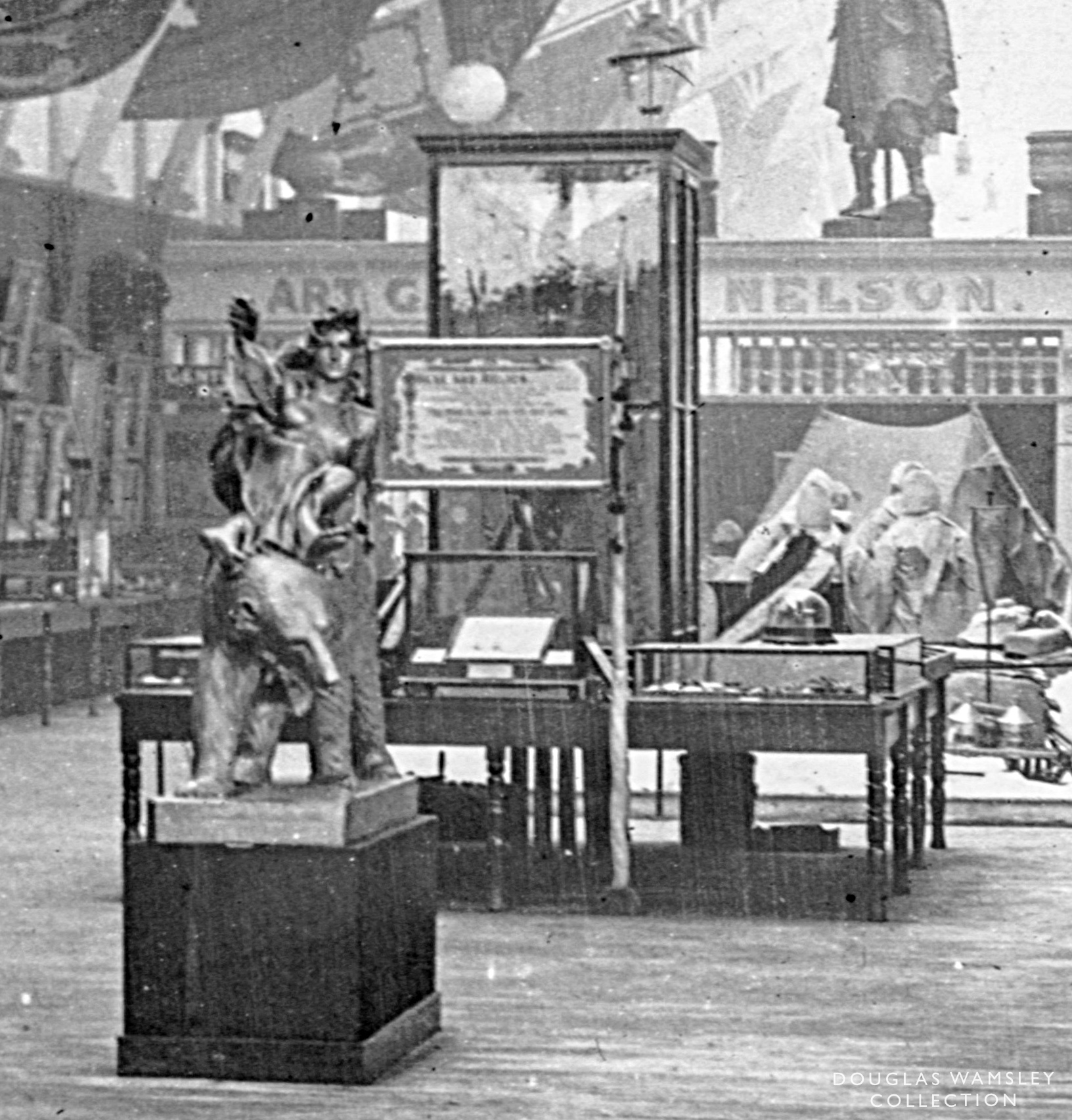

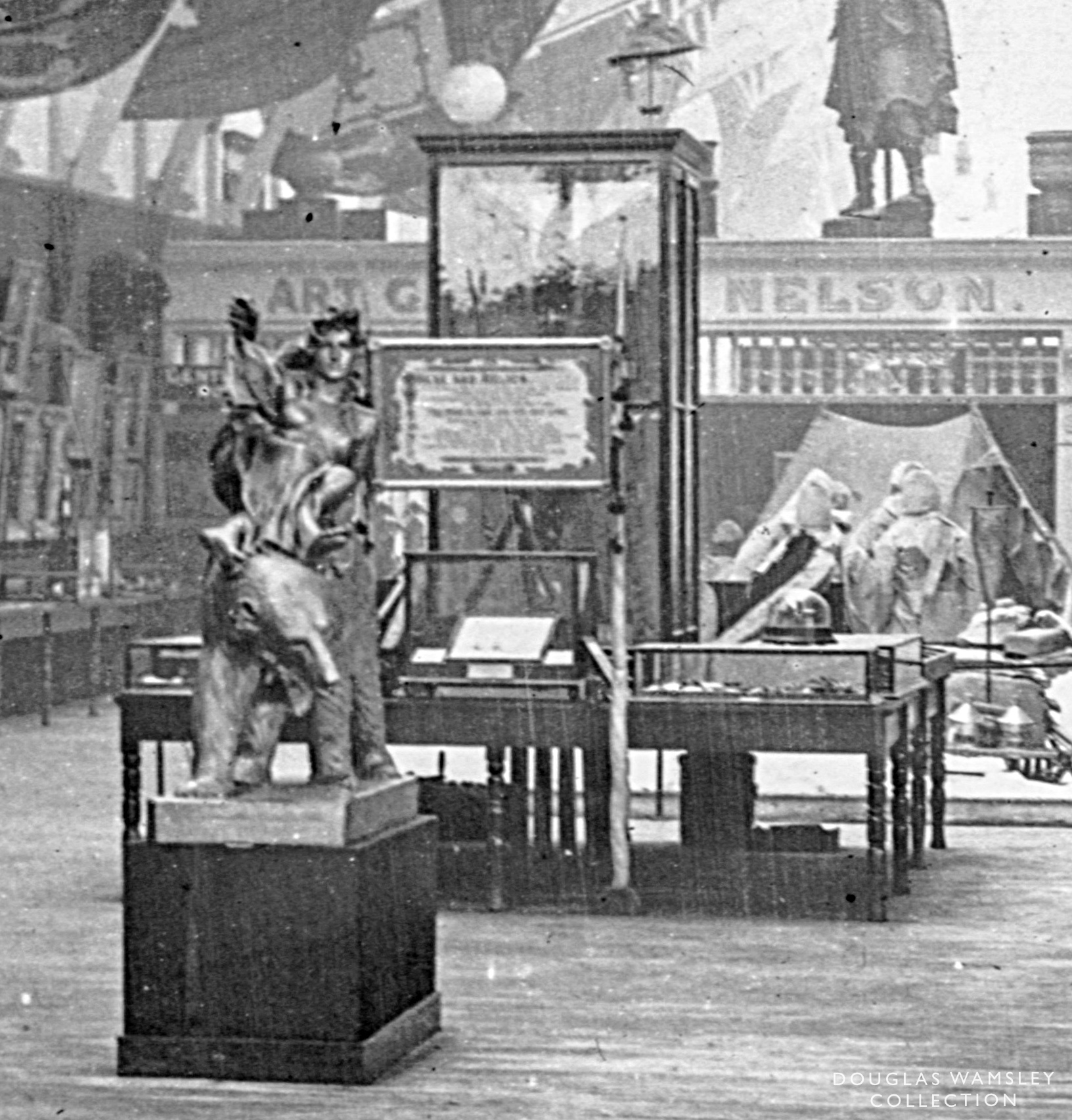

The photograph shows a wider view of The Graphic newspaper’s sketch seen above. We see the same tent in the distance, but with another team of mannequins now visible, manhauling a sledge across fake snow. On the wall beyond are portraits of eminent Franklin searchers, with artifacts below too distant to discern.

However, a glance at the exhibition’s catalogue tells us just how much we are not seeing. This cannot be the entire exhibit. For one thing, the Franklin Gallery was supposed to have a life-size model of the Victory Point cairn. For another, there should be an allegorical statue of a naked woman riding a polar bear (representing ‘Polar Spirit’). Clearly neither is visible in the photograph. What was behind the camera’s view here? What paintings and artifacts were held on the opposite wall? What does it say on that triangular flag flying from the sledge?

These questions, and the impossibility of ever answering them, have intrigued me on a scale with the question of where McClintock’s ‘Fox’ docked in London, or the source of the alleged Franklin relics buried in Abraham Lincoln’s coffin. But that one single photograph was not the end of the story. Over the past several years, I have learned that more photographs of the Franklin Gallery do exist, previously unanalyzed, at Greenwich and in a private collection — but just one and a half more.

To these, we will add a few slivers hiding along the edges of nearby photographs. Examining details inside each, this guide will simulate a visit to the 1891 Franklin Gallery. All images marked with the “▽” deck prism symbol can be clicked to download at high resolution. Keep a sharp eye out: the vast majority of the objects in these photographs await identification, and new identifications were being made right up until publication.

ENTERING THE ROYAL NAVAL EXHIBITION

{ ▽ Official Daily Programme, 24 September 1891 }

{ Full issue available in the Bibliography. }

{ ▽ A medal from the Royal Naval Exhibition. }

{ ▽ Map of the exhibition. Engineering, 13 February 1891. }

{ A rediscovered photograph of the RNE’s entrance. }

{ Stead, 1891. Image courtesy Douglas Wamsley. }

The Royal Naval Exhibition was not an annual fair; there was not an “R.N.E.” for 1890 or 1892, etc. It was one long summer in 1891, from May to October, attracting over two million visitors (Jephson 1892). It was held in west London, on the grounds of the Chelsea Hospital for military pensioners (across the Thames from the later Battersea Power Station). Two London newspapers acclaimed it as the best exhibition since the Crystal Palace, forty years earlier (Lewis-Jones 2005a; Daily Telegraph/Daily Chronicle, 4/8 May 1891).

The photographs that follow are almost all from a lantern slide series created at the time. [Lantern slides are two pieces of glass taped together with a photograph trapped between, which is then projected onto a screen before a crowd.] This series was devoted solely to the Royal Naval Exhibition, and was accompanied by a booklet of suggested readings for each image.

Had we bought a ticket in 1891 and entered the Royal Naval Exhibition through the main entrance, we would have spilled directly from the turnstiles into the Franklin Gallery, followed immediately by the Nelson Gallery. However, as Franklin is our destination, we should begin with a few photographs showing just how grand the rest of the exhibition was — as if we had arrived by sneaking in through a gap in the back fence.

{ A gate marked “Naval Exhibition” with children peering in. }

{ ▽ Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 16 May 1891. }

The Royal Naval Exhibition was Roman in scale: they built an artificial lake for mock naval battles, showing off not triremes but torpedoes.

{ ▽ Miniature warships battle. Graphic, 9 May 1891. }

{ ▽ Crowds line the shore for mock battles with real explosions. }

{ Detail from photograph below. }

Torpedo men demonstrating a Whitehead torpedo: “No vessel could survive the shock caused by the explosion of one of these missiles properly directed and exploded under her bottom” (from the suggested lantern slide reading for this image; RNE Optical Lantern Readings, 1891).

{ Detail from photograph below. }

Alison and I count fifteen distinct faces in the full photograph (below).

{ ▽ Torpedo men with a Whitehead torpedo. }

The large wheel behind the torpedo men is Pain’s “Mammoth Silver Fire Wheel,” part of an evening fireworks display (RNE Daily Programme), and visible in all of these Lake photographs.

{ ▽ Miniature warships battling. }

The RNE exhibition buildings in the background are (left to right): the huge Trafalgar panorama, the towered P&O steamship pavilion, and the “George” grill with balcony seating (and a clock showing a little after 5).

{ ▽ Boom. }

{ ▽ Inside the Trafalgar panorama building. }

{ Detail of sailors in photograph below. }

{ ▽ Sailors with electrically-controlled boats. }

{ Detail from photograph below. }

{ ▽ Queen Victoria visits the RNE, at the P&O steamship pavilion. }

{ ▽ The Heroine. }

Above is the ‘smack’ Heroine, an old North Sea fishing trawler out of Yarmouth.

{ ▽ Model of HMS Victory. }

The principal attraction of the Royal Naval Exhibition was their full-size model of HMS Victory. Inside on the orlop deck, visitors encountered a Tussaud’s wax tableau of the death of Nelson (RNE Catalogue #5334). The ship was entered via an exterior staircase, seen distantly in this image (marked by signs strictly prohibiting smoking and stating the closing time). In the above photograph, there is someone looking at the camera from inside the nearest gun port.

Glancing at the map of the RNE, it seems perverse that this main attraction was set in a distant corner of the exhibition. But a sketch from across the river (below) shows a likely explanation. In such a position, the Victory’s stern — and her decorative gingerbread-work — overlooked the Thames, doubtlessly pulling in much attention from traffic on the river. The visitors seen here getting off at the “Victoria Pier” start by walking towards that view of the Victory (though they are about to learn that the entrance into the RNE is down past the model lighthouse).

{ The Victory’s stern from the Thames, on the right-hand side. }

{ ▽ Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 6 June 1891. }

{ A rare close photograph of the RNE Victory model’s stern. }

{ Stead, 1891. Image courtesy Douglas Wamsley. }

{ ▽ The Arena. }

Opposite the RNE’s artificial lake was a field called the Arena, seen above during cutlass drill. On the far left we can see a bit of the RNE’s grand stand seating, with uniformed band members before it holding their instruments on the field’s edge. [And on the distant horizon, we can see the twin Victorian Gothic towers of the old Chelsea Bridge, wickedly demolished in the 1930s.]

{ ▽ The Graphic, 8 August 1891. }

{ Detail from photograph below. }

Balloons were launched from inside the Royal Naval Exhibition. Inflated with hydrogen gas, they carried a half dozen passengers thousands of feet into the air; after landing, balloon and basket were “packed up and carted to the nearest railway station” (RNE Lantern Readings).

{ ▽ Balloon. }

{ GIF juxtaposition of the previous two ‘Arena’ photographs. }

{ Detail from photograph below. }

{ ▽ The “mandoline band,” photographed in the galleries’ Quadrangle. }

{ ▽ A bandstand in the galleries’ Quadrangle. }

Above is the ‘Quadrangle’ enclosed by the RNE’s western galleries, with a bandstand to fill the secluded space with music. One of the long gallery buildings can be seen distantly through the tree branches on the right; it is the Seppings Gallery (and thus the Franklin Gallery is here behind us and to the right).

Everywhere hanging from strings are multicoloured lights, for evenings here to “present a fairy-like scene” (RNE Lantern Readings). Deep in the background, we can just see Gordon House through the trees (brick, left), and next to it the open terrace of the “Ward Room” café. The lantern slide readings tell us that this terrace café was generally crowded at night (the RNE was open till the surprisingly late hour of 11 o’clock at night; RNE Catalogue, page xvii). At high resolution (below), it is possible to just make out the backs of the chairs in the “Ward Room.”

{ Detail of the distant café. The letters “...NE” appear on the hillside. }

{ Detail from photograph below. }

{ ▽ The Iceberg pavilion. }

[Running behind the Iceberg pavilion is the RNE’s St. Vincent Gallery, with the chimneys of Chelsea Hospital beyond.]

{ Detail of entrance to Iceberg, from photograph above. }

{ ▽ HMS Investigator beset inside the Iceberg pavilion. }

A model of HMS Investigator was the nucleus of the Iceberg pavilion, her name written on the bow as if she were a pre-Dreadnought. Investigator was a Franklin search ship, effectively making the Franklin presence at the RNE not just a dedicated gallery but also an entire separate pavilion. An accompanying electric light show simulated the Aurora Borealis. [RNE Catalogue #5353; RNE “Colossal Iceberg” pamphlet.]

{ Detail from photograph above. }

{ ▽ The Howe Gallery, with staircase to the Cook Gallery. }

With this photograph, we move into the galleries, thick with exhibits that went on for over half a mile. The above image is the north end of the Howe Gallery, with the Cook Gallery just up the stairs. But for our purposes, it is the staircase itself (with the words “He Won’t Be Happy Till He Gets It” repeated on each step) to make a visual note of.

{ ▽ The Cook Gallery, facing northeast. }

[In this Cook Gallery photograph, there is a sign for Parkinson & Frodsham, makers of one of the two chronometers found at the ‘Boat Place.’]

{ ▽ The Blake Gallery. }

{ ▽ The Blake Gallery, silver ship models. }

{ ▽ The Camperdown Gallery, RNE Catalogue #5150. }

{ Telegraph buoy. Illustrated London News, 9 May 1891. }

This huge object, hung with chains and various wicked-looking anchors, was a buoy of the “Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company of London.” It was painted red, and has the company flag flying above it. The long ship model in front (left) is likely Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Eastern, in her later career laying deep sea telegraph cables.

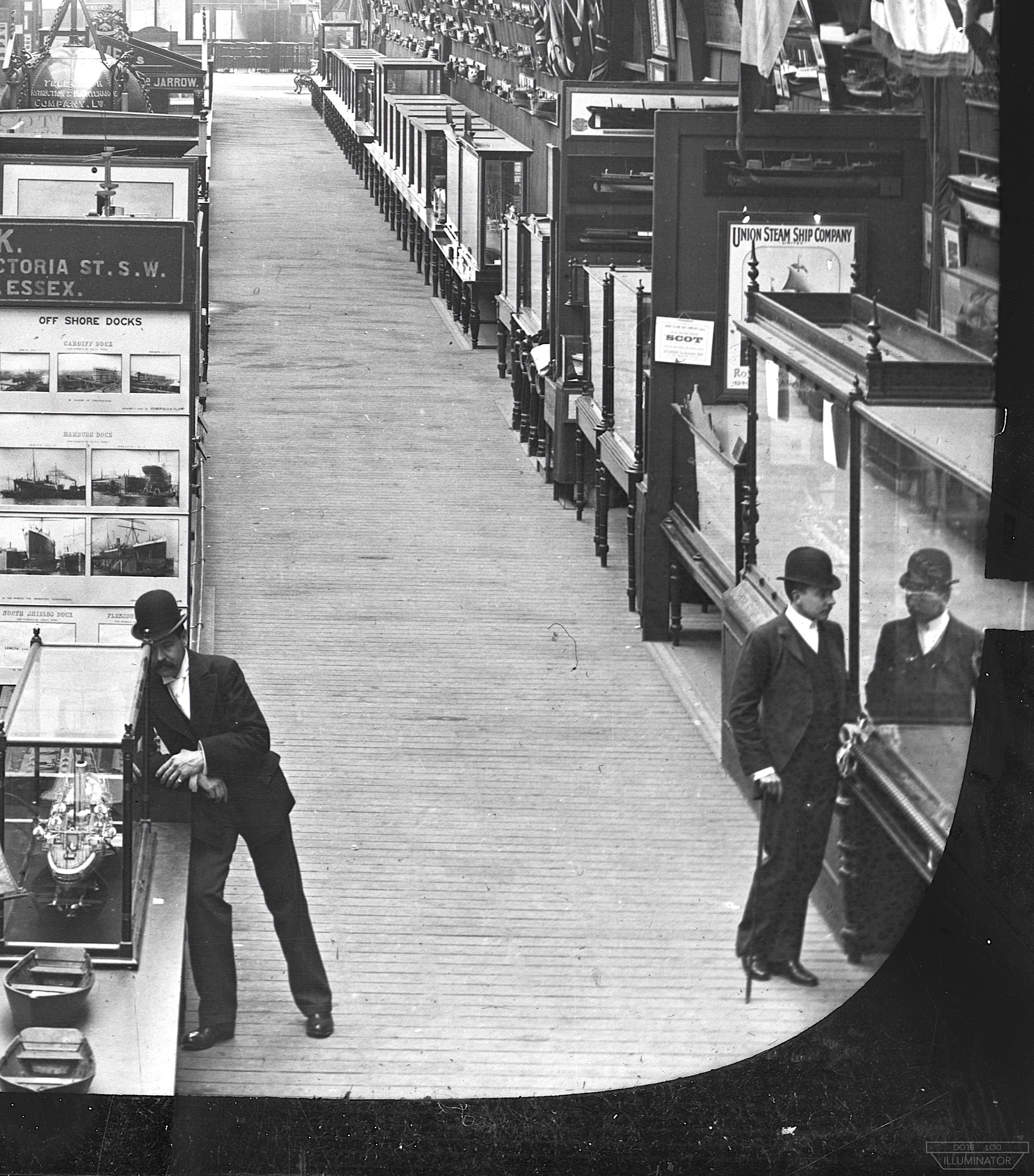

{ ▽ Telegraph buoy in the Seppings Gallery. }

The Catalogue of the Royal Naval Exhibition tells us that the telegraph buoy (#4508) was located in the Seppings Gallery. That means that the above photograph was taken very close to our destination, the Franklin Gallery.

Seppings—who was Seppings, that he should have his name given to a gallery? Nelson we know, and Blake, and Benbow, but Seppings—who in the name of wonder was Seppings?[W.T. Stead, How to See the Royal Naval Exhibition, 1891.]

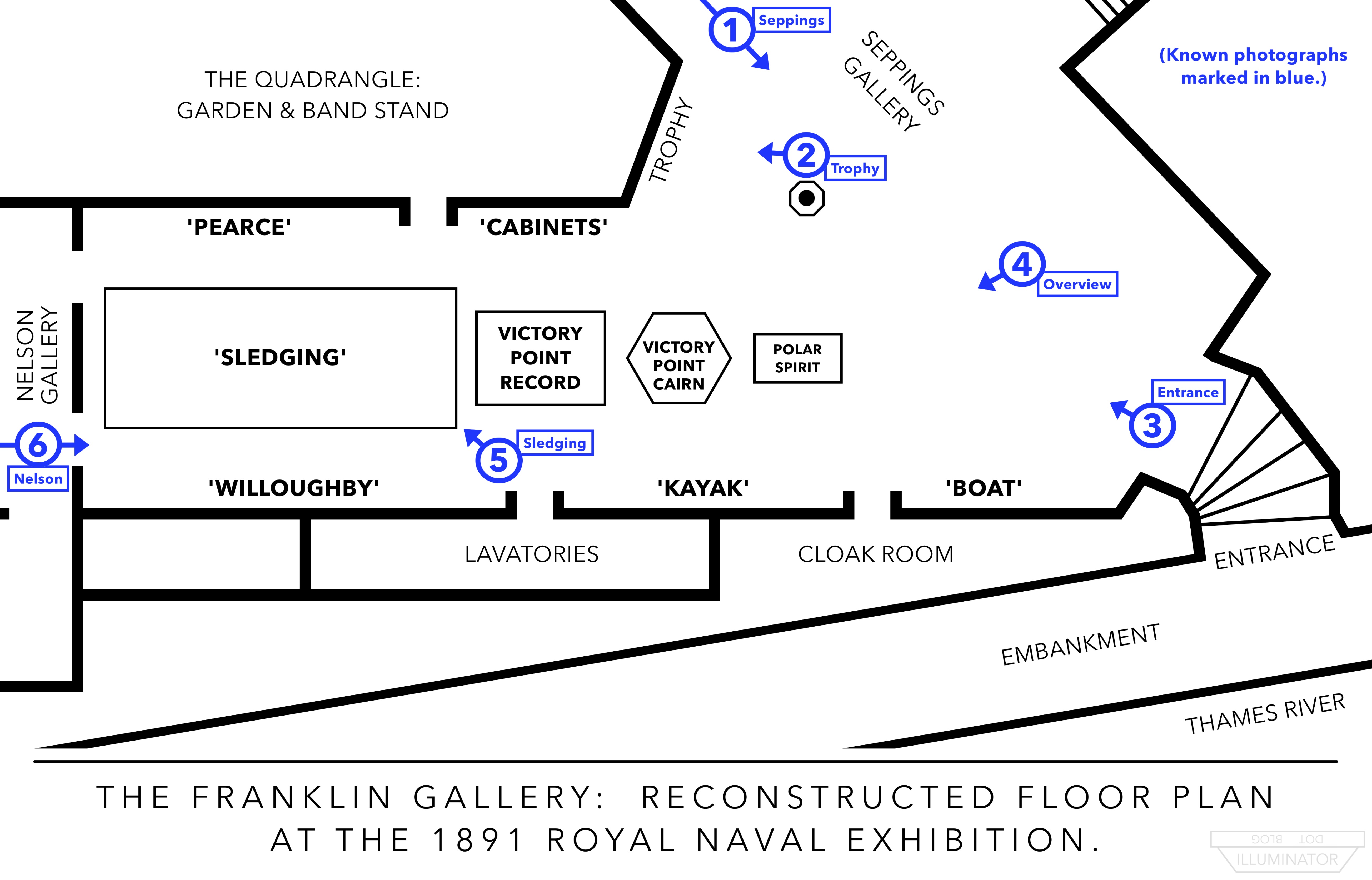

The hall of the Seppings Gallery connected to the Franklin Gallery at its east end (detail below). At their junction was also the main entrance to the Royal Naval Exhibition, facing the Thames.

Halfway down the gallery is a flag flying, illuminated by light. It is the flag of the same telegraph buoy that we saw earlier.

A photograph of the Trophy survives in the RNE lantern slides series.

Those cabinets facing away from us are part of the Franklin Gallery’s exhibits. The top cabinet has a glass side. Though we can see into it, I have not been able to guess what artifact is inside.

Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum also has a photograph of the Trophy. But theirs is different: it is taken from much further back.

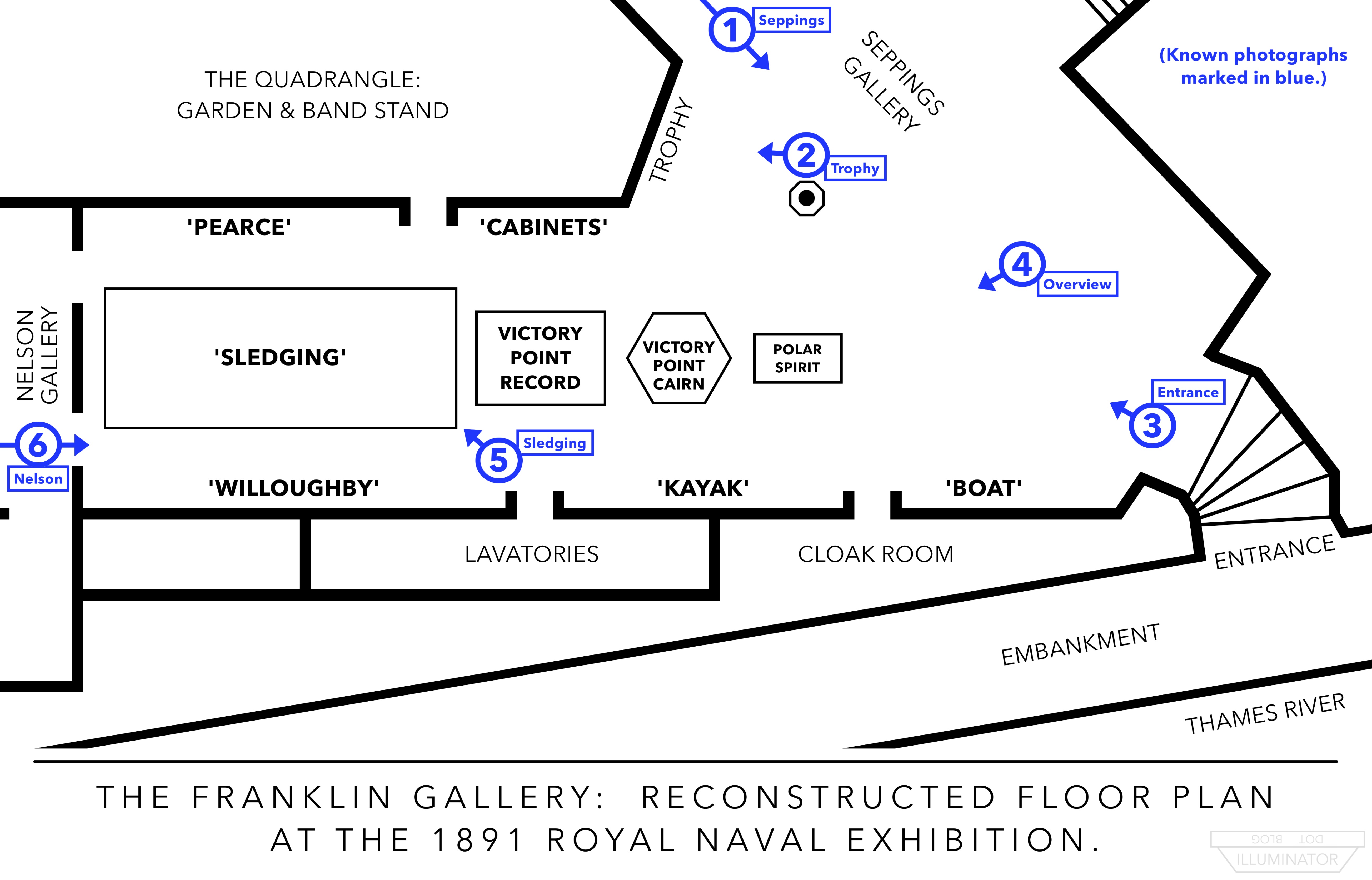

The most recognizable new exhibit is the one in the middle. Visitors had said that there was a model of the Victory Point cairn in the Franklin Gallery (Washington 1892; St. James’s Gazette, 15 July 1891). In the photograph, we can distinctly see a conical mound of snow-covered rocks. As Leopold McClintock was directly involved in realizing the Franklin Gallery (Times, 4 Feb 1891; Preston Herald, 28 March 1891), this is one of the few depictions of the Victory Point cairn overseen by someone who had actually been there.

{ Detail from RNE map above. }

{ Two Victorians posing. }

I do not know the names of these two gents in bowler hats.

But by the sign hanging above them, we can tell that they are in that same Seppings Gallery.

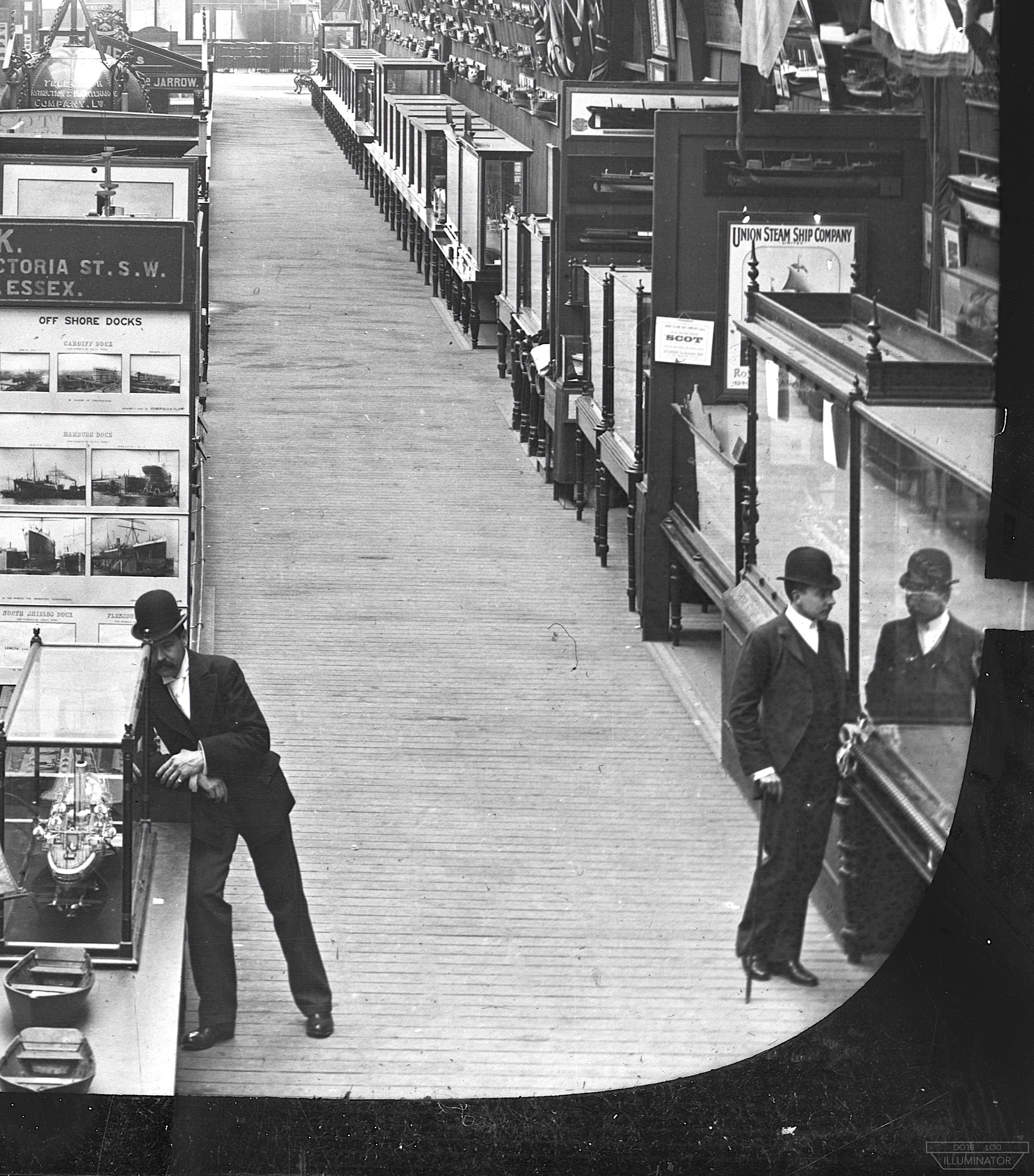

{ ▽ The Seppings Gallery. }

If the Seppings Gallery connected to the Franklin Gallery at one end, then which end are we looking towards here? If this photograph were facing north, then we ought to see a stairway at the far end — a twin of the stairway we saw earlier when facing north in the Howe Gallery. Instead, our height above the two Victorians suggests that, in fact, we are atop that stairway, looking down at them, and towards the Thames.

Nor do we see any stairs in the far distance. Instead, we see light.

{ Far end highlighted. }

Halfway down the gallery is a flag flying, illuminated by light. It is the flag of the same telegraph buoy that we saw earlier.

{ Detail from photograph above. }

Above is a closer look at the photograph. In the immediate foreground, we see the big telegraph buoy with the flag above it. Just above that buoy, but much further back, there is a sign. It seems to say “Way Out.” To the right of these, there is a telltale row of turnstiles. That light, the lack of stairs, the “Way Out,” the turnstiles... We are seeing the main entrance to the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition: from the inside.

What an unusual view — how many of us enter a museum or gallery and immediately turn around, to photograph whatever was 180º behind us as we entered? On the other side of that light would be the Thames. Before the river would be Embankment (the street), with a line of Victorians along it waiting to enter the exhibition. This was the scene where, ticket in hand and at last passing through the gates, the millions had to choose a path: one of the forked galleries stretching away before them, or hard right to the outdoor exhibits they’d peered at while standing in line. In their rushed anticipation, not one in a thousand might have recalled this scene behind them. Yet here we can still see it. There is a clock above the door, showing us what time this photograph was taken; I think it reads about 11:20.

{ Entrance detail. }

If we could walk down to those turnstiles and face right, we would then be looking directly into the Franklin Gallery hall. We are seeing the edges of it here in this photograph. There is a small booth with a canopy and a word above it; I have been unable to guess the word (though it may be another “Way Out” sign).

And if we could walk down there, we would also see the entrance “trophy,” a statue of Britannia that divided the Seppings Gallery from the Franklin Gallery, greeting visitors as they entered.

{ The Trophy under construction (and the Iceberg as well). }

{ Photograph by A. Freebairn. Daily Graphic, 1 May 1891. }

{ National Library of Scotland (licence). }

{ The Trophy completed. Illustrated London News, 9 May 1891. }

A photograph of the Trophy survives in the RNE lantern slides series.

{ Detail from photograph below. }

{ ▽ The Britannia Trophy. Weapons, flags, and potted plants. }

You may recognize this Britannia: she was made from a cast of the Britannia still standing atop the Armada Memorial in Plymouth, including her pet lion (RNE Catalogue, p. 1).

From this vantage, we can peek into the Franklin Gallery. That’s it around the corner to the left. We can just discern the mannequins manhauling a sledge, seen in the photograph at the start of this article.

{ Detail of peek. }

Those cabinets facing away from us are part of the Franklin Gallery’s exhibits. The top cabinet has a glass side. Though we can see into it, I have not been able to guess what artifact is inside.

{ Detail of glass cabinet. }

Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum also has a photograph of the Trophy. But theirs is different: it is taken from much further back.

{ ▽ The Britannia Trophy. }

Above: the Trophy again close up.

Below: the Trophy from a distance.

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (ALB1386.1). }

In this invaluable photograph, we see what visitors first saw upon entering the Royal Naval Exhibition. In the middle is the Trophy. On the right is the Seppings Gallery; earlier we looked down this gallery from the far distance, and now we are looking back up it. The turnstiles we saw earlier must be right behind us now.

And on the left, finally, what I imagined I would never see: another surviving photograph of the Franklin Gallery.

{ Detail from photograph above. ©NMM (ALB1386.1) }

This photograph was included in an album purchased by the museum in 1996. That critical left edge with the Franklin Gallery is quite blurry, and perhaps for this reason it has gone unanalyzed until now (cf. Van der Merwe 2001, Lewis-Jones 2005a). This photograph doubles our visual knowledge of the gallery’s layout and exhibits. From this image, we can begin to create a floor plan.

To do so, we must connect this image to the sledging photograph that we began with. Where are those manhauling mannequins? They are far away, all but eclipsed behind three new exhibits on the main floor that previously we could not see.

{ The Franklin Gallery highlighted on the RNE Catalogue map. }

{ Franklin Gallery initial floor plan. }

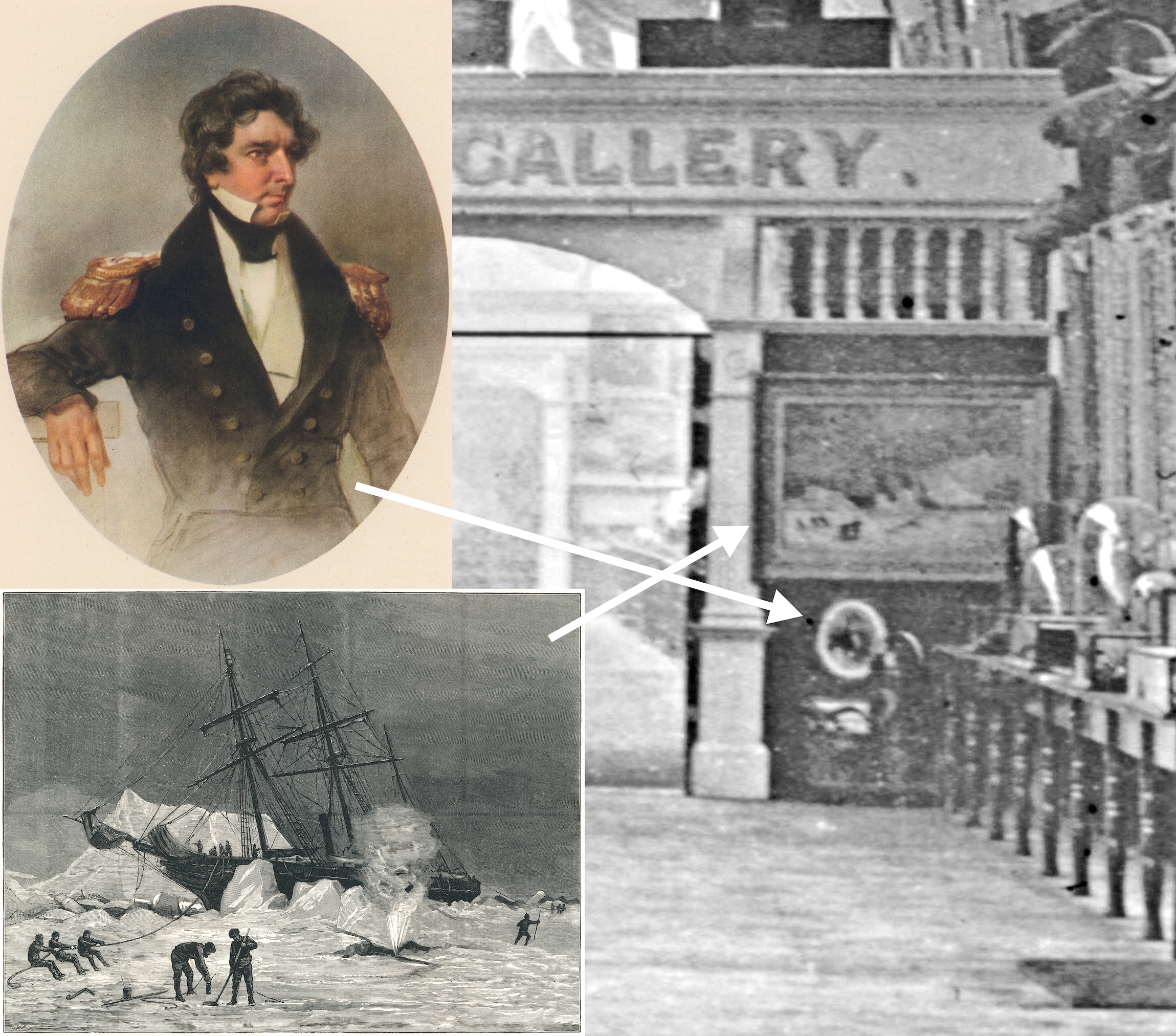

{ ▽ The Victory Point cairn in The Illustrated London News, 15 Oct 1859. }

The most recognizable new exhibit is the one in the middle. Visitors had said that there was a model of the Victory Point cairn in the Franklin Gallery (Washington 1892; St. James’s Gazette, 15 July 1891). In the photograph, we can distinctly see a conical mound of snow-covered rocks. As Leopold McClintock was directly involved in realizing the Franklin Gallery (Times, 4 Feb 1891; Preston Herald, 28 March 1891), this is one of the few depictions of the Victory Point cairn overseen by someone who had actually been there.

{ Detail from previous photograph. ©NMM (ALB1386.1) }

In front of the Victory Point cairn is the statue entitled The Polar Spirit by Ferdinand Junck, representing “the Spirit of Arctic Research.” Polar Spirit was variously described as: a somewhat dishevelled lady, a Northern maid, stark naked riding upon a Polar bear, with her hair blown forward, one arm aloft holding a compass.

All that is quite hard to discern in Greenwich’s photograph above.

However, we can now turn to the final new photograph for this article.

{ Lantern slide courtesy Douglas Wamsley. }

With this new angle, we can make sense of the previous view of the sculpture. We can see the polar bear, and two bare human feet (crossed) above his head. Polar Spirit herself has her right arm aloft, holding up what must be the compass.

[The Victory Point cairn has gone missing in this photograph, a detail we will return to.]

This image of The Polar Spirit is just one small bite taken from the following lantern slide.

{ ▽ The Franklin Gallery. Lantern slide courtesy Douglas Wamsley. }

This extraordinary photograph comes from the collection of polar author Douglas Wamsley. In one image, we can see almost everything in the Franklin Gallery that was previously hidden from view.

{ Detail from lantern slide above. }

Along the Thames wall, dozens of paintings and prints are now visible. As of publishing this article, nearly every one of these remains unidentified (and this despite the titles of the works being listed in the RNE’s Catalogue, and the signature on one of the unidentified paintings here being close to readable).

The large sledge with boat lashed atop is from the George Nares expedition of 1875–76, part of its shield having been deciphered (see Appendix 3). And an object above came into focus just prior to publishing. Notice that there are vertical supports along the wall. The one closest to us, behind the boat, has an odd detail lower down: it has sharp little teeth sticking out.

This is not to prevent museumgoers from climbing the walls: it is an ice saw, for cutting channels through the ice. And, it may well be the same ice saw on display today at Polar Worlds in Greenwich (#AAA4058, see image below). If you zoom in on each, they both have the same pattern of three bolts in a triangle securing the blade to the handle. [And the crossbar seen only in the 1891 photograph (at the top) may survive today as Greenwich’s artifact #AAA4042 (link).]

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (AAA4058). }

Despite these nearest paintings not yet being identified, a handful much further down the gallery have been figured out. We must walk all the way down to the end of the Franklin Gallery, to the dividing wall separating Franklin from the Nelson Gallery. Here two paintings have been identified almost at the limit of the lantern slide’s resolution.

{ Franklin Gallery overview with arrow to dividing wall. }

{ Detail from lantern slide above, with two comparisons. }

Thanks to researcher Alexa Price, the small oval image can be recognized as a portrait of James Clark Ross held by the RGS (known from the RNE Catalogue to have loaned a portrait of Ross to the Franklin Gallery). The larger painting on top is Pandora Nipped In Melville Bay by W. W. May, seen here compared to the Illustrated London News sketch (25 Nov 1876) which revealed its identity; the figures of five men in the lower corner are a distinct match.

These paintings were previously obscured from our view in the manhaul sledging photograph (seen at the start of this article, and below). They were hidden behind the first mannequin in the team.

{ Image highlighting smocks. From photograph below. }

At this high of resolution, we can see something new here: these are not plain smocks. There are cartoons drawn on the back of each. The clearest is the last man in the team; we can discern the eyes and nose of a face. This sledging tableau was created with material from Nares’ North Pole expedition of 1875–76 (RNE Lantern Readings; Stead 1891). Greenwich has a surviving example of one of the Nares expedition smocks (link to #AAA3998); in addition to its own cartoon, it has a ribbon across the bottom somewhat similar to the last smock in the photograph above.

In the paintings above their heads, you may have spotted that third from the right is James Clark Ross. Isn’t it odd that a painting of Ross would be here, when we just saw an oval portrait of James Clark Ross a few steps to the left?

Nor is that all. Just a few steps to the right is yet a third depiction of James Clark Ross. He is the man with the white pompadour in the center of Pearce’s The Arctic Council. Even for ‘The Handsomest Man In The Navy,’ this is a lot of Ross held in one corner.

{ Detail of Pearce’s The Arctic Council. From photograph further below. }

And, despite this being the Franklin Gallery, Sir John’s ghostly portrait inside The Arctic Council painting (top center-left) is the only depiction of Franklin yet identified in these photographs. [...and of James Fitzjames, fainter still in the oval portrait next to him.]

Paintings on this wall were noted as being works by the Arctic portraitist Stephen Pearce. The most identifications had been made by the National Maritime Museum, who identified six portraits in their photograph (#ALB1386.3). For this article, Alison Freebairn has identified an additional nine. One of these new identifications is in fact not by Pearce (Captain Cook, by Dance-Holland). Click the image below to see her proposed identifications; this brings the total paintings identified on this wall to fifteen, with at least two at the far end still unknown.

{ ▽ Portraits with Freebairn’s new identifications. }

There is a Union Jack hanging beneath Robert McClure’s portrait. According to the RNE Catalogue, the Franklin Gallery featured a “Union Jack carried home through the North-West Passage in McClure’s Expedition.” Given how closely it is tacked to his portrait, we are likely seeing that flag here.

{ ▽ The manhaul sledging tableau in the Franklin Gallery. }

{ Detail of left/Thames wall, from Doug Wamsley’s lantern slide. }

Turning to the side of the gallery that we could not see before: in the far distance (past a short staircase), we can see the more thick and ornate frames characteristic of oil paintings.

{ Willoughby painting marked by arrow. }

One has been identified, that of Hugh Willoughby, “frozen in the north sea in 1553” as the text beneath his hat reads (though not legible in the above print). Willoughby and two ships disappeared in that year looking for a Northeast Passage (but unlike Franklin: the ships, their bodies, and Willoughby’s journal were soon found).

The picture frames of the nearer section (below) are different in appearance, and more resemble prints of Arctic scenes; Douglas Wamsley identified sea and landscape prints by May, Moss, and Inglefield here just prior to publishing. On the counter appear to be several narwhal tusks and two pairs of walrus tusks. In contrast to the mannequins displaying British dress and equipment in the Arctic, here we see a mannequin representing the Inuit in the Arctic, seated in a kayak.

{ ‘Kayak’ section, from Doug Wamsley’s lantern slide. }

In front of the kayak is an Inuit sledge. It is a decent visual match for a bone sledge used by Capt. Edward Parry that The Daily Graphic had sketched as being present in the Franklin Gallery (below, top right).

{ Bone sledge used by Parry (item #3). Daily Graphic, 8 May 1891. }

Taken all together, this section appears to be devoted to Inuit culture, backgrounded with imagery emphasizing Arctic scenery over British portraiture. And from this, a coherent layout of the entire gallery can be suggested: clockwise chronologically, by earliest presence in the Arctic.

To begin with, we saw that immediately past this section was a painting of Hugh Willoughby, who lived in the 1500s. And across the gallery, the paintings of the 1800s Franklin searchers seemed to ‘end’ (on the far left) with an earlier explorer: James Cook, from the 1700s. These placements would make sense if one imagines moving clockwise chronologically.

And to the right of the Franklin searcher portraits section (‘Pearce’) is an area with currently no artifacts yet identified, simply marked ‘Cabinets’ on the floor plan below. A visitor report from 1891 suggests what may be there: “In a large glass case on the right of the gallery were shown the sledge banners used by the North Polar Expedition under Sir George Nares...” (Washington 1892; Italics mine. – L.Z.). As no such display appears in the ‘Pearce’ section, this description must refer to the unknown ‘Cabinets’ area. George Nares’ North Pole expedition was then the most recent of all, from 1875-76.

The same visitor report also suggests a chronological route by asserting that the portraits section “began” with Willoughby, despite the photography showing us that Willoughby’s painting was hung deep inside the gallery.

The left wall was covered with polar charts and cartoons of Arctic and Antarctic scenery, and on either side of the gallery were exhibited portraits of Arctic explorers, beginning with Sir Hugh Willoughby, who perished with all his crew in 1554, and continuing down to Cook, Parry, Franklin, and Officers of our own day...[Washington 1892; Italics mine. – L.Z.]

{ Franklin Gallery floor plan with clockwise chronological route. }

Taken all together, this suggests four chronological zones in a clockwise course around the gallery perimeter: Inuit (‘Kayak’), pre-Franklin exploration (‘Willoughby’), Franklin Searchers (‘Pearce’), and finally Nares (‘Cabinets’). As a visitor intent on seeing everything would be inclined to hug that outer/Thames wall, this floor plan would naturally direct them into the section devoted to Inuit culture first (as would an initial stop at the Cloak Room).

[When I entered Ottawa’s Death in the Ice in 2018, that exhibition also began by hugging an outer wall directly into a section on Inuit culture. The most salient differences from 1891 were that: Death in the Ice moved counter-clockwise, it did not deploy half as many mannequins, and it substituted George Nares with Doug Stenton & Parks Canada.]

It should be noted that a rope appears to prevent walking behind the tent (observable in the sledging tableau lantern slide), requiring a brief entry into the Nelson Gallery to complete this circuit. Spatial concessions are also made along the way, e.g., Captain Cook’s large portrait is put with the equally-large Franklin searcher portraits, and the large Nares ice boat is not forced into the small Nares section, etc. Or so I imagine: I have left the tentative artifact names for each section on the floor plan, not pushing categories onto them yet, so as to leave the matter open for others to reconsider.

There is one section missing from this clockwise chronology: Where are the Franklin Expedition relics themselves? The only display left unaccounted for is the table at the center of the gallery, between the cairn and the sledging tableau.

As mentioned earlier, the Victory Point cairn is missing from Doug Wamsley’s lantern slide. It should be right behind Polar Spirit. This absence can be explained by newspaper reports, which tell us in mid-July that the Victory Point cairn had only just made its debut, two months after the exhibition had opened (e.g., St. James’s Gazette, 15 July 1891). [And this also tells us that Wamsley’s photograph was taken earlier than Greenwich’s.]

The absence of the cairn is much to our advantage, as it gives us a clear view of the unidentified exhibit behind it.

{ Detail from Doug Wamsley’s lantern slide. }

Without making any identifications, one visitor report can be used to confirm that this centerpiece exhibit was indeed the location of the Franklin relics:

In the central space beyond the cairn, the relics recovered from the lost expedition, including the record, were arranged in glass cases upon a large table. ... In the centre stood a trophy of fourteen flags, all being banners carried by sledges employed in the Franklin search. The remaining central space of the gallery was occupied by a representation of an ice-field or floe, on which was exhibited in realistic form the mode of sledge travelling adopted in our Arctic expeditions...[Washington 1892; Italics mine. – L.Z.]

When examining the photograph above (or even Greenwich’s), that description becomes unambiguous: the Franklin relics are here, between the (missing) cairn and the mannequins’ ice-field, with an upright “trophy” cabinet for fourteen sledge flags.

From this distance, what can be identified?

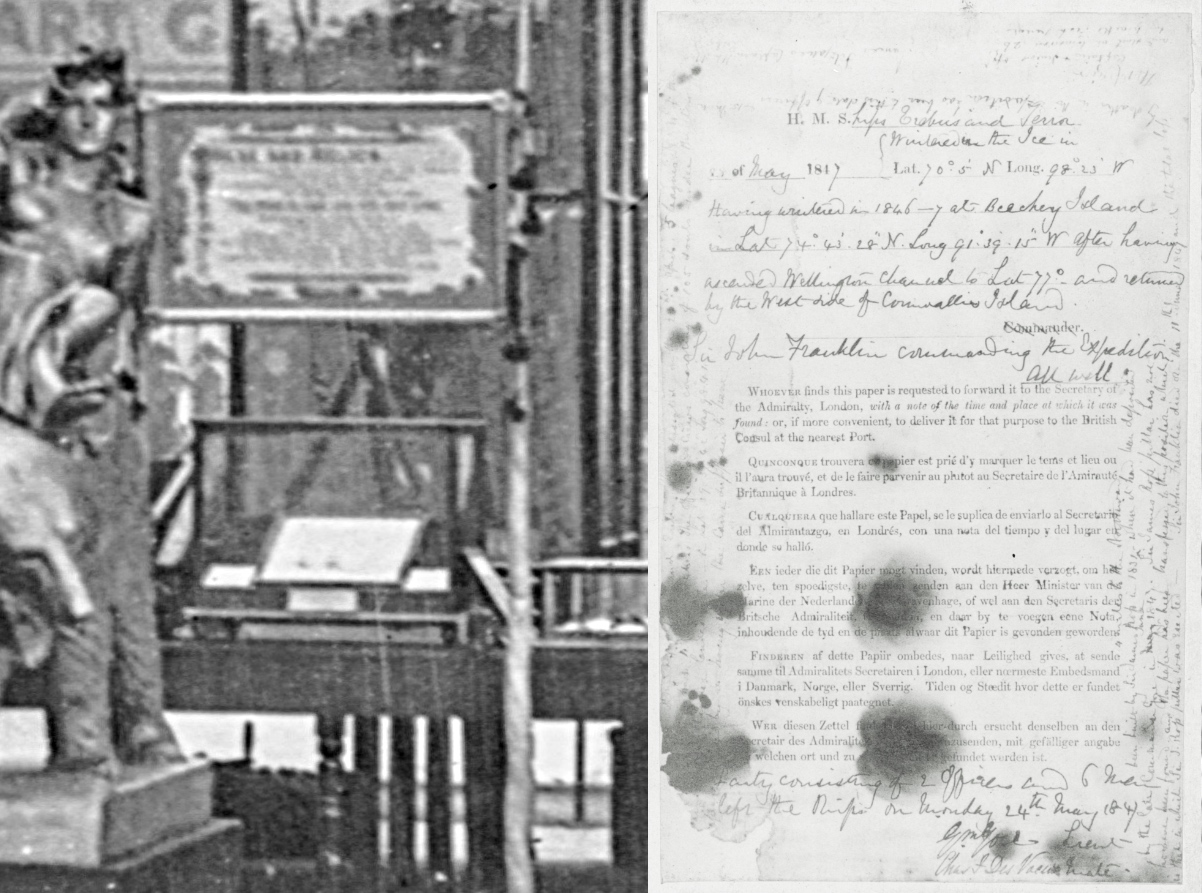

Two vertical narwhal tusks support a rectangular sign with writing on it. These frame a single glass cabinet below, which appears to contain... almost nothing. There are no three-dimensional Franklin relics inside. There is only a flat frame tilted upwards at an angle.

{ Detail of central glass cabinet. }

That flat frame has only one identifiable feature: dark spots near the bottom, slightly offset to the left.

There is a famous Franklin relic that has dark spots near the bottom, also offset to the left.

{ Images (L/R) courtesy of Doug Wamsley and Kenn Harper. }

It is the Victory Point Record. And what else could have warranted this position? The two smaller frames on either side are perhaps transcriptions of the 1847 and 1848 notes respectively, with a small nameplate centered beneath.

And we have a witness who described where in the gallery the Victory Point Record was displayed. Annette McClintock, wife of Leopold the searcher, published an essay devoted to the 1891 Franklin Gallery. In it, when she comes to the Victory Point Record, she tells us that it was located, “in the central glass case.” That otherwise vague statement agrees perfectly with the above image: the glass case in the middle of the table, at the center of the Franklin Gallery.

How unusual that the first Franklin relic identified in these old photographs would be this one, a mere sheet of paper. The slightest reflection in the glass would have prevented us from seeing those spots. To my knowledge, this is only the second photograph of the Victory Point Record taken in the 19th century (the other being Cheyne’s from 1859, seen above courtesy of Kenn Harper).

{ Annette Elizabeth McClintock, née Delap; born 1840, died 1920. }

{ Photograph provided by her great-grandaughter, Sylvia Wright. }

* * *

This ought to be the conclusion of this tour. We can now see the 1891 Franklin Gallery from multiple photographs, with enough angles to draw a floor plan, and enough artifacts identified to suggest the overall organization.

{ Franklin Gallery reconstructed floor plan. }

However, there is one more item to examine here. It will allow us to pull part of the 1891 Franklin Gallery out from black and white and into modern 2022 color. And, it again involves Annette McClintock.

While I had looked at the Victory Point Record beneath, Alison Freebairn focused on what appeared to be writing on a sign above it.

{ Detail of the sign. }

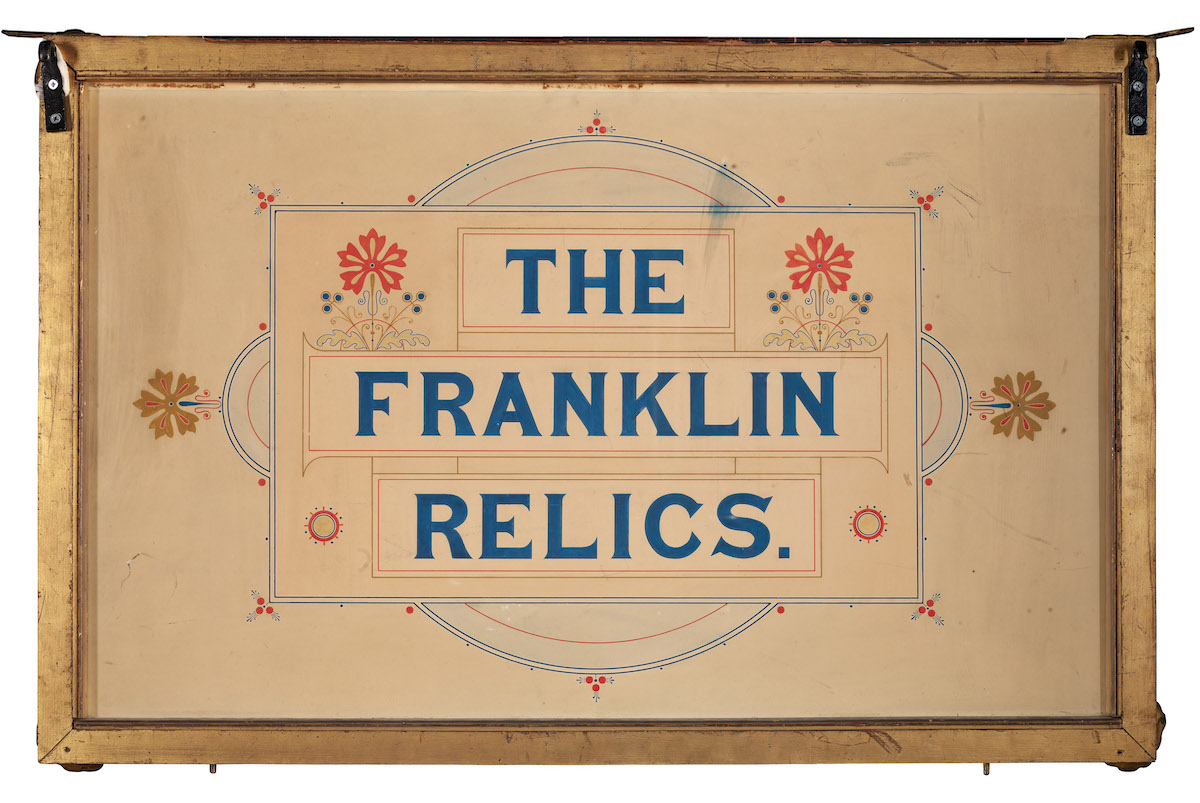

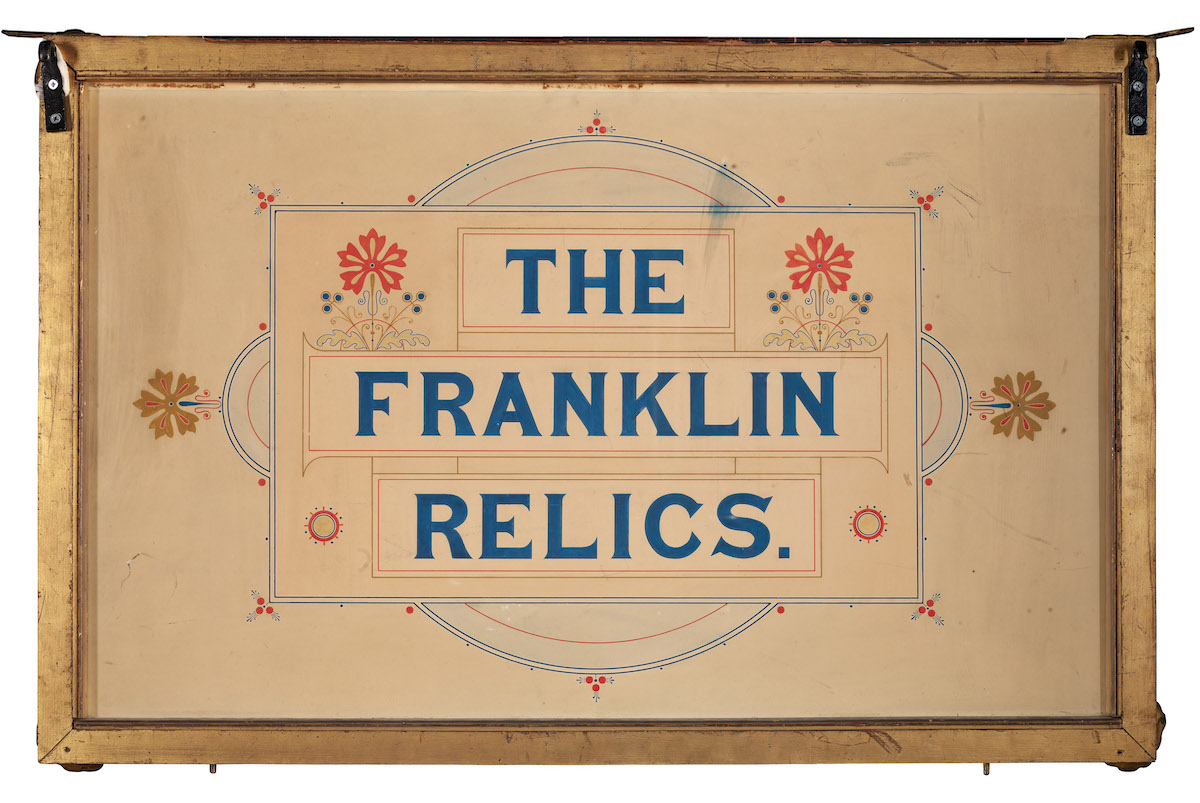

This is not a Franklin relic. It would have been a custom piece of the 1891 exhibition itself. I recall Alison saying that the first line looked like three bold words, and that the last word of those three might be “Relics.” One can squint and see how that fits. Later she came back and proposed a solution for the entire top line: “These Sad Relics.”

These sad relics... That phrase rang a bell. Leopold McClintock had used that phrase when he came to the Boat Place in his book The Voyage of the Fox. He had also recently reused the phrase in his letter to The Times (4 February 1891) asking for private relics to be offered for display at the Franklin Gallery.

{ Page 295 from McClintock’s The Voyage of the Fox. }

Now, returning to our own time, there is an artifact surviving today at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum, with cryptic lines printed on it regarding the Franklin relics. It is described as a framed sign or notice a little more than 3 feet wide. All provenance for this artifact has been lost to the past, such as who created it, when, and where it was hung. There is no imagery available, only this description.

The museum does note that it must have been made “After 1859,” as that year is mentioned in the text on it. In addition to Franklin, the text references Admiral Nelson and General Gordon.

And that text begins with the same three words Alison had just read off the Franklin Gallery photograph: “These sad relics are all that has come back to us of the expedition under Sir John Franklin...”

That Greenwich’s sign referenced General Gordon was now a clue. Gordon was not remotely connected to Arctic exploration. And while Gordon was famous before his death, it is unlikely that his fame would have spilled over into Franklin’s realm prior to his imperial martyrdom at Khartoum. That occurred in 1885. This would suggest that the museum’s sign was in fact created much later, after 1885 — which would put it very near to the time of the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition.

Indeed, Greenwich’s sign mentions Gordon right at the end, quoting him with, “England was made by her adventurers.” In her essay on the Franklin Gallery, Annette McClintock had also mentioned General Gordon right at the end — and she had done so using that same quote.

Thus confident that this could be the same ‘These Sad Relics’ sign she had deciphered in the Franklin Gallery image, Alison requested that the sign at Greenwich’s museum be pulled out from storage and photographed.

While she waited, we sent the argument to Russell Potter. Russell dug further and found an article in a Scottish newspaper by a woman who visited London in the summer of 1891 (Dundee Evening Telegraph, 21 July 1891). This woman, Marguerite (“Our Own Lady Contributor”), toured the Royal Naval Exhibition, and actually wrote out a lengthy inscription which she said had ‘surmounted’ the Franklin relics. Tellingly, she discusses this immediately before coming to the Victory Point Record, as if the two were located close to each other in the gallery. Marguerite’s transcription is nearly a word-for-word match for the transcription of the sign at Greenwich. And her transcription begins with the words, “These sad relics...”

As well, I returned to an 1891 newspaper that Russell had alerted me to years earlier, with rare sketches of Franklin relics at the RNE. Turning the page, I saw a scene that was now instantly familiar.

{ Photograph by Alison Freebairn. The Queen, 30 May 1891. }

{ National Library of Scotland (licence). }

At a glance, this is the Victory Point Record exhibit at the Franklin Gallery, just as we saw in Doug Wamsley’s lantern slide. In the tall upright cabinet, we can now clearly see the search sledge flags hanging inside. And the artist places the words ‘These Sad Relics’ on the sign right where Alison had said they were.

Alison has since received new photography of the sign without provenance at the National Maritime Museum, which she can share for this article.

It is a match.

{ Sign at the 1891 Franklin Gallery. }

{ Sign without provenance at Greenwich’s museum. }

{ © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London }

{ The sign above the Victory Point Record. }

{ The reverse of the ‘These Sad Relics’ sign. }

Reading the words carefully shows us that Annette McClintock and this sign did not merely share that one General Gordon quote. Annette McClintock had also used the phrases “sad relics” and “forged the last link” in her essay, as the sign does. And the sign’s list of virtues — “Courage, Discipline, and Devotion to Duty” — is the same troika (in the same order) used by Annette McClintock in the first line of her essay. We therefore believe the anonymous author of the ‘These Sad Relics’ sign is likely to have been Annette McClintock herself, her pen already flowing from having written one or the other first.

All of this information in Alison’s argument was sent to Jeremy Michell, Curator of Polar Relics at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum. Michell reviewed the case and has since updated the museum’s public record (link to artifact #AAB0506). That record now identifies the museum’s ‘These Sad Relics’ sign as coming from the Royal Naval Exhibition of 1891, having hung above the central case in the Franklin Gallery.

As such, it is the most outstanding remnant of the 1891 Franklin Gallery to have survived to the present day.

* * *

Many other objects in these Franklin Gallery photographs await identification. Indeed, more were identified as this article was prepared for publication. Douglas Wamsley identified the rows of imagery behind the kayak as the Moss chromo-lithographs from the Nares expedition. And in a separate annex to this article, I will argue that one silhouette beneath the Franklin relics display is a match for a stove that Schwatka recovered from Victory Point. Full (and future) identifications will be listed in Appendix 3.

The End.

– L.Z. November 20, 2022.

This article owes a debt of gratitude to Sylvia Wright for answering questions and offering family photographs of her great-grandmother, beginning back in 2018 when Sylvia first explained to Alexa Price and I that it was her ancestor who had authored the essay discussed in this article.

{ Sylvia Wright, née McClintock, great-granddaughter of Annette McClintock, }

{ with husband Malcolm and grandchild. }

Annette Elizabeth McClintock, née Delap, was born in 1840 and died in 1920. She married Leopold in 1870 and they had five children. Sylvia notes that while her great-grandmother Annette was born a Delap, her father later changed the family name back to Dunlop (as it had been before the family emigrated from Ayrshire to Sligo in the early 1600s). Annette is buried under a large Celtic cross in City of Westminster Cemetery (now Hanwell) alongside her husband, as well as a daughter and a sister. For Annette McClintock’s exact grave location in the cemetery, see “A Franklin Expedition Guide to London” (link).

This article also owes a debt of gratitude to author Douglas Wamsley. His polar collection was instrumental in identifying a number of rare prints in the Franklin Gallery, as well as providing first views of the stern of the Victory model and the main entrance on the Thames — to my knowledge, photographs never before seen in modern analyses of the Royal Naval Exhibition. Wamsley also provided the rare Franklin Gallery lantern slide which is the centerpiece of this study; without it, the majority of this article would simply not be here.

* * *

APPENDICES

1. Additional notes and imagery.

2. Alternate source versions.

3. Full artifact identifications.

4. The lantern slides and other photographs.

Bibliography.

Appendix 1: Additional notes and imagery.

It’s striking to see photography from an exhibition on British polar exploration with Scott and Shackleton nowhere in evidence. Shackleton was a teenager in 1891; their voyage on the Discovery together was only 10 years in the future. At the Royal Naval Exhibition, we see the final moments of Franklin’s long cultural dominance before ceding the field to newcomers. It would be nearly a century till the lead stoker from HMS Terror propelled Franklin back to the forefront.

{ ▽ Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 16 May 1891. }

{ ▽ Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 16 May 1891. }

{ ▽ Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 16 May 1891. }

One rare RNE photograph is now missing. It was a view of two men in a stand, the older man with a large white beard, selling Wildes Ship Tobacco in one of the galleries. A cropped photo of it appeared in Huw Lewis-Jones’ PhD thesis in 2006. When I contacted the Royal Navy museum in Portsmouth about the original, they told me it had since disappeared. Please contact me if you know more, or if you have a surviving full view of this lost lantern slide. [For more information on all RNE photographs, see Appendix 4.]

Regarding the Victory Point cairn, it should be noted that what McClintock would have seen in 1859 was the cairn as rebuilt by the sledge party of his lieutenant, William R. Hobson (McClintock’s Voyage of the Fox: “Hobson removed every stone of this cairn down to the ground and rebuilt it.”). How closely Hobson’s men rebuilt the cairn to the shape and height of Crozier’s is unknowable, although the stones used would almost certainly be the same (just for simplicity, given the snow covering the ground, plus the need to get the ill Hobson back to the ship). Hobson was dead by the time of the Royal Naval Exhibition (died 1880) — and so was his sledgemate, Edwards the Carpenter (see my April 2022 article of the same name). It is also possible that the early newspaper sketches of the Victory Point cairn were from a design endorsed by McClintock (see Appendix 1 in my August 2022 article “Sketches of ‘Peglar’”). It should also here be noted that the accepted location of Victory Point has moved a few miles up the shore from where Crozier, Fitzjames, Hobson, and McClintock had decided it was (see Richard J. Cyriax’s 1952 “The Position of Victory Point, King William Island” in Polar Record).

In an article discussing the Victory Point Record earlier this year (link), I quoted “Marguerite” commenting that the VPR was still blue in color when she saw it in 1891: “The most touching relic is the last record written by the survivors, brown faded writing meandering round the margin of the blue official folio...” (Dundee Evening Telegraph, 21 July 1891). I’d noted that, “As the original VPR was still blue in 1891 – thirty years after its recovery – this may indicate that it was thereafter exposed to sunlight somewhere in London.” Looking now at the skylight roof we see in these Franklin Gallery photographs, the Victory Point Record in its central glass cabinet was likely exposed to sunlight most days from May to October of that year. Potentially, the reason we know the Victory Point Record as a brown not blue document today is the summer it spent at the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition.

This “Marguerite” writing for the Dundee Evening Telegraph — who has here given us critical details on both the Victory Point Record and the ‘These Sad Relics’ sign — is likely to have been Jessie Margaret King, an activist and one of Scotland’s first full-time female journalists. A photograph of King at her desk exists online (link), seen on the cover of Charlotte Lauder’s 2021 article on King in the Victorian Periodicals Review: “The conquering feminine”: Women Journalists and the People’s Friend Magazine, 1869–1905 (link).

P.S.—I would like to correct a provoking little error which crept into the first line of the Franklin epitaph, as given on Tuesday. It should run, of course—“Not here. The White North hath thy bones,” &c., instead of “my,” which makes nonsense of it, or worse. M.

[“Marguerite” in Dundee Evening Telegraph, 24 July 1891, page 4.]

Journalist (and Titanic victim) W.T. Stead writing in his guide to the RNE:

“The walls are hung with pictures of Arctic worthies, although Lady Franklin, but for whom Arctic exploration would have perished of inanition for at least a quarter of a century, is conspicuous by her absence. There are portraits and to spare of the Arctic Council and the Arctic navigators whom they sent out, but of the woman whose fiery zeal and unswerving devotion made these stout admirals her willing instruments there is not a trace.”[W.T. Stead, How to See the Royal Naval Exhibition, 1891.]

{ Aberdeen Press & Journal, 6 May 1891. (source) }

One known Arctic mannequin is still missing. Two newspapers sketched a mannequin up in a crow’s nest at the RNE (one is seen above), which I cannot yet find in these Franklin Gallery photographs. One visitor reported it as “by the entrance” to the Franklin Gallery (Marine Engineer, 1 May 1891). Both sketches show a barrel attached to a mast with a rope ladder below; in The Queen’s sketch (30 May 1891, page 852), the mannequin holds a telescope. Interestingly, Greenwich’s museum still holds a Nares Expedition crow’s nest today (#AAA4312, currently on display in Polar Worlds), with both a shield and rope ladder similar to The Queen’s sketch. When I contacted curator Claire Warrior at the museum, she recalled that a mannequin was in their Nares crow’s nest as recently as the 1980s.

Also in the above sketch, below the crow’s nest depiction, readers of this site will recognize a relic identified (wrongly) as “A Franklin Relic.” It is a sign reading “Observatory A.D. 1824-25,” which I wrote about in May 2020 (link).

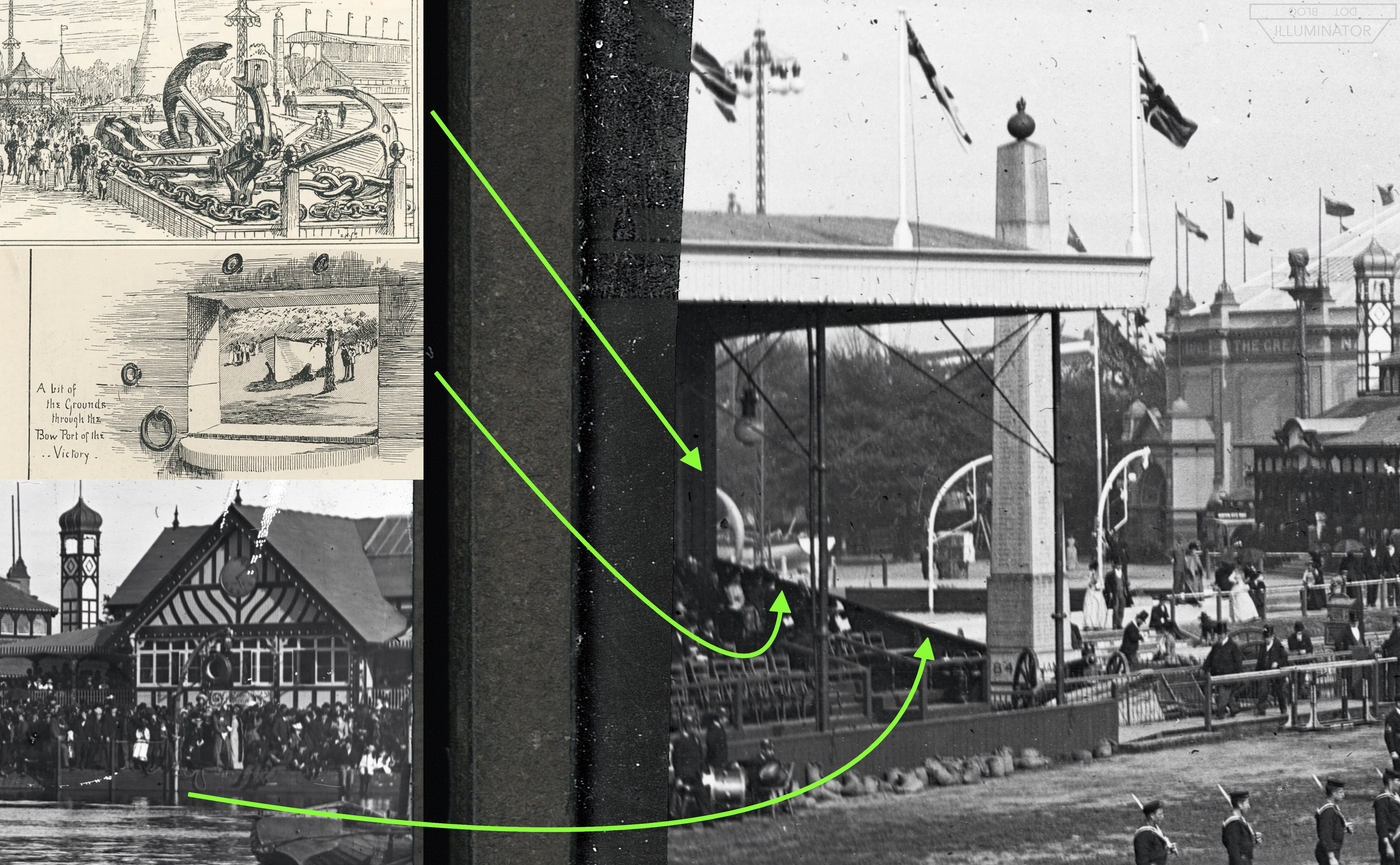

{ ILN, 9 May 1891; Sporting and Dramatic News, 6 June 1891; }

{ Lake lantern slide (two ships); Arena lantern slide (cutlass). }

The above right-hand photograph (Arena cutlass drill slide) is useful for tying together some less prominent features on the map. From top to bottom, I believe the photograph is showing us: the “monster” Hingley anchors display (RNE #5331), a boat that was sketched just west of the Victory model, and the two davits at the edge of the Lake seen in other photographs. The obelisk nearer to us – memorializing the January 1849 Battle of Chillianwala, its year and month visible at the base – is one of the only structures in these photographs still surviving on the site today.

As the middle newspaper sketch above states, that small boat was seen through the port side of the life-size Victory model. Where is the Victory then? The huge model is here: one of our only images of it. If you look closely at the distant trees, you can see a bright stripe rising above the treetops – and at the right end, two of the stern lanterns are just visible. In the shadows beneath the trees, an even bigger stripe and several gun ports can be discerned.

As to the small boat: there may have been further boats on display in that area. However, in the photograph below, the middle arrow points at the only part of the crowd where people in back seemed to have found something to stand up on. My guess is that they are standing on that (one) boat, the same seen in the above sketch and photograph.

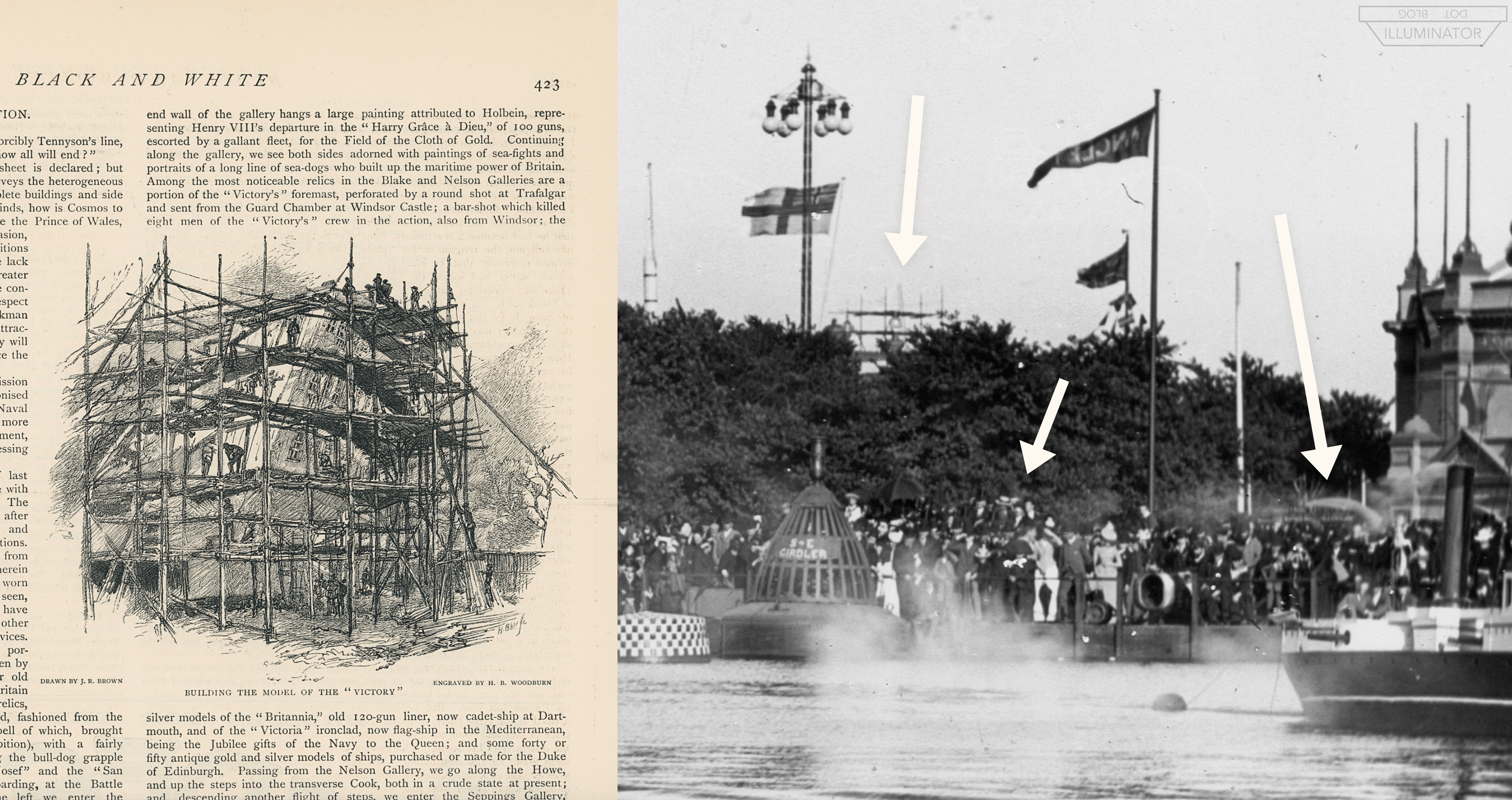

{ Black and White, 2 May 1891; Lake lantern slide (with explosion). }

In this Lake photograph, where we ought to see the Victory over the trees (leftmost arrow), we instead see a strange bit of scaffolding. But a sketch happens to exist of the Victory model under construction, showing her stern covered in just such scaffolding (Black and White, 2 May 1891).

The rightmost arrow (above) points to what I believe is an anchor fluke peeking above the crowd from the Hingley anchors display, seen again in the lower right corner of the sketch below (RNE #5331; RNE Catalogue map #28).

{ ▽ “Sketches at the Royal Naval Exhibition.” ILN, 9 May 1891. }

After the exhibition ended, the Victory model escaped the clutches of firewood merchants bidding a fraction of its original construction cost. Instead it would reappear a year later in the Irish Sea, at an exhibition in Douglas on the Isle of Man (Van der Merwe 2001). Franklinists will recognize this story’s similarity to that of the full-size model of HMS Terror/Erebus, built for the AMC television series The Terror. The model effectively vanished after filming, to be rediscovered years later by Twitter persona @forautumniam at a theme park in Hungary (link). [An article in Dundee’s The Courier covered this story (“The Terror 2,” 24 Aug 2021), although @forautumniam is not among the people interviewed for her discovery.] For detailed information on the Terror/Erebus model, see Matthew Betts’ newly-released book HMS Terror: The Design, Fitting and Voyages of the Polar Discovery Ship.

The RNE’s towered P&O pavilion was re-erected at Devonshire Park in Eastbourne, surviving until the surprisingly late date of 1963 (when it was demolished to make room for the modernist Congress Theater; see Appendix 4).

{ ▽ Illustrated London News, 16 May 1891. }

The above sketch is one of our only views of the Lake looking west. Above the grand stand seating, we can see three giant images of people. I have not found a source mentioning who was represented here. Two of them could be Franklin and Nelson, for instance, given their prominence at the RNE. However, it is just as likely that these may be Pears Soap ads (as appear in RNE publications and around the edges of many RNE photographs). Higher up, there is a square tower with a mushroom shape on top. The RNE Daily Programme tells us that a powerful search light was mounted atop the grand stand seating, and this may be it. It also says that one other search light was located by the Trafalgar Panorama, and if you return to either GIF in this article, you will see a similar mushroom shape appearing and disappearing on a platform near the Trafalgar Panorama roof.

The artificial Lake was measured as 250 feet by 150 feet (Elliot 1891). On its novelty, it was commented that, “...from the innate love of Englishmen for anything in the shape of water, even a boat with two or three people crossing the lake was enough to draw a small crowd” (Jephson 1892).

{ Howe Gallery (left) and Mandoline Band photos. }

We lack names for almost everyone who appears in these photographs, especially those working at the RNE. However, author Glenn Marty Stein (Discovering the North-West Passage, 2015) has been able to suss out part of the careers of the two petty officers pictured above, which one day could help identify who they are. Stein believes that the man with the mutton chops (Howe Gallery) is wearing an Egypt and Sudan Medal 1882–89 with two clasps and Khedive’s Star, and that the clean-shaven man (Mandoline Band, also in Electric Boats on Lake) is wearing ribbon bars for the Egypt and Sudan Medal 1882–89, Naval Long Service & Good Conduct Medal, and Khedive’s Star.

{ Two shots by the Lake of Lionel Wells. }

We believe these two Lake photographs (above) are of the same man: Lionel de Latour/Lautour Wells (“Wills” in the lantern slide readings). Several other photos of him are available online, similar to these poses. A newspaper article on him from 1903 reads like the first time Parker Snow saw Captain Penny:

“A man you would like to go to sea with is Captain Wells. He inspires confidence at a glance. The manliness of that big chest, those broad shoulders, and that neatly trimmed black beard, need only the confirming intelligence of the clear grey sailor's eyes to declare that here is a man indeed. And then the hearty ring of that great voice, which one could well imagine rising above the roar of a tempest at sea or of flames on land. You have not been in his company many minutes before you are impelled to the conclusion that there is no set of circumstances conceivable under which Captain Wells would lose his head. He has always come out at the top.”

[Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 1 October 1903.]

Franklin searcher William Parker Snow, now very aged, wrote about visiting the 1891 RNE. Having failed to organize a group visit with other Arctic veterans like himself, he had to make the trip alone: “...as I feel almost on my beam-ends and nearly a wreck. I attended the opening as an outsider, to remind me of doing the same 40 years ago at the Hyde Park Exhibition; but the drenching rain did me no good, and there is little probability of my attending again.” [Dated 11 May 1891, to the editor of The Daily Chronicle.]

Another famous visitor was Kaiser Wilhelm II. The Kaiser was specifically noted to have toured the Franklin Gallery (Shields Daily News, 10 July 1891), and his wife Auguste Viktoria was reported as asking an attendant to show her the HMS Investigator light show a second time (Dundee Courier, 17 July 1891).

The motto inscribed in a circle behind the RNE’s Britannia trophy, adapted from the Articles of War (RNE Catalogue, page 1), was apparently a favorite phrase of Sir John “Jacky” Fisher (Hamilton 1977, page 91), the jolly modernizer who would prepare the Royal Navy to face the Kaiser’s new fleet in World War 1. Fisher had earlier served under McClintock, and referred to him in his memoirs as “a rare old bit of mahogany” (Memories, 1919). McClintock commented on Fisher’s ebullience that he “almost requires wiring down” (Bacon, The Life of Lord Fisher of Kilverstone, 1929). Fisher attended McClintock’s funeral in London as First Sea Lord.

As mentioned earlier, the Royal Naval Exhibition was held on the grounds of the Chelsea Military Hospital. Why would a naval exhibition be held on the grounds of a military hospital? Why was it not held at the Royal Navy’s (former) hospital, in Greenwich? One reason is that some of the RNE’s buildings already existed from a military exhibition held on the site one year earlier. Another reason was given by RNE organizer Alfred Jephson in the RUSI Journal (1892): “With regard to the site there was little to choose from: Greenwich was by almost common consent vetoed on account of its distance from town, and no doubt hundreds dropped in to the Exhibition of an evening who would never (considering the weather) have journeyed down there.”

The National Maritime Museum’s entrance photograph (#ALB1386.1) shows placards for “Medals” in several places, most gauchely on the base of Polar Spirit. A medal commemorating the Royal Naval Exhibition was shown at the start of this article (link to image). Very small letters on the obverse read: “A. E. Warner, London.” Occasionally these medals are seen today with the original box still intact, inside which is written: “Alfred E. Warner. Engraver & Medallist. 10 Wardour St. London, W.” One of the two ships on the obverse is HMS Camperdown, which two years after the RNE would ram and sink HMS Victoria during a suicidal fleet manoeuvre (her wreck still stands vertically at the bottom of the Mediterranean).

Appendix 2: Alternate source versions.

For anyone working on artifact identifications in the Franklin Gallery, I have come across three Franklin Gallery sources with version issues to be aware of.

The first is that I have seen two different versions of Annette McClintock’s essay. [There may be more that I have not found.] The differences begin on page 10, and are contained within the paragraph that begins, “Being fully persuaded...” In the longer version, she talks about the gallery’s model cairn and quotes directly from the Victory Point Record’s 1848 note, while in the other version she does neither, simply summarizing the 1848 note. Given that we know the model cairn did not appear in the gallery until July, this suggests that the essay not mentioning the cairn is the earlier one. Also, at least in the PDF editions I have seen, her name only appears on the final page of the cairn version of her essay (as “Annette E. McClintock”).

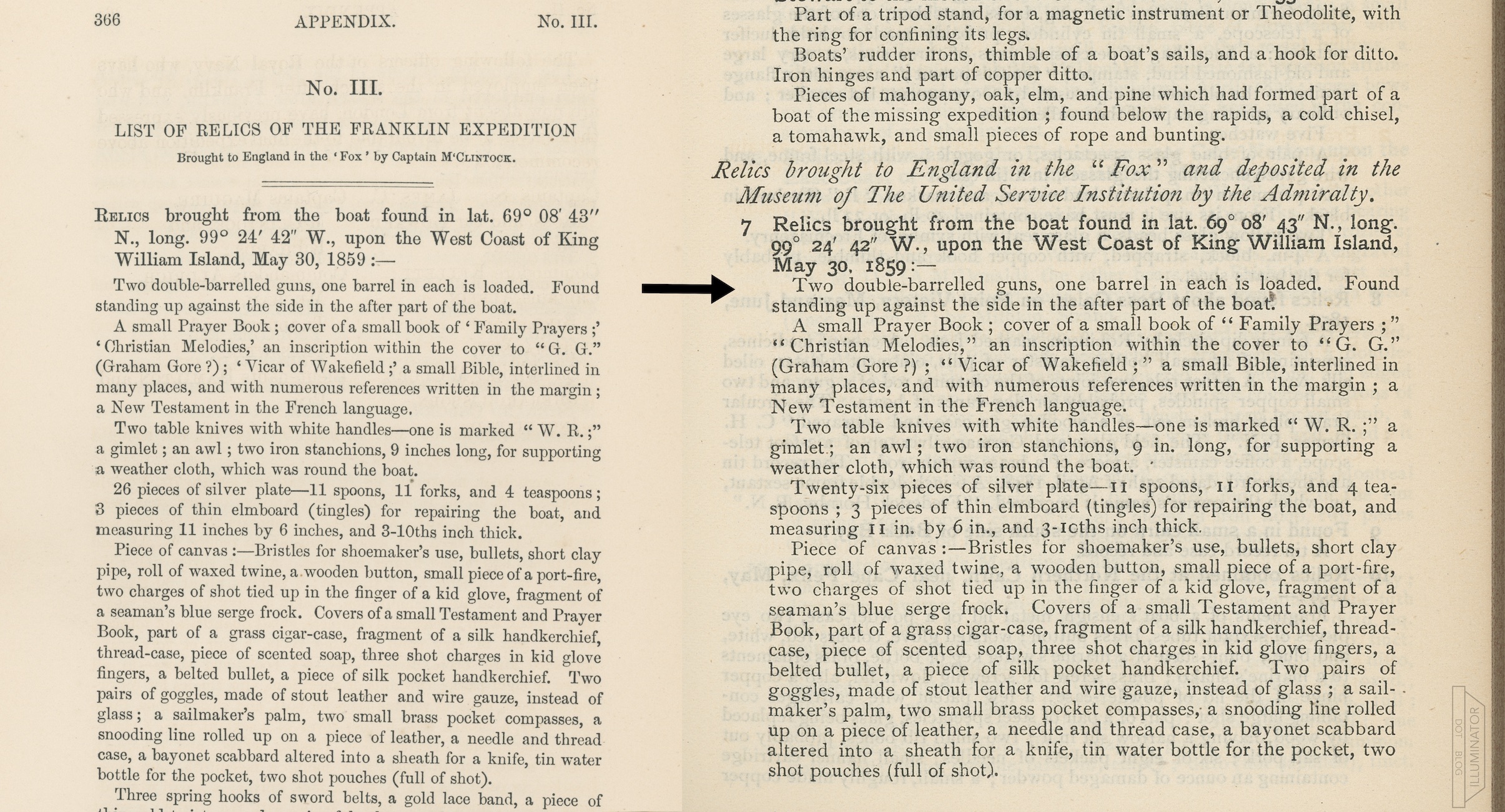

The second issue I have found is that, unfortunately, the list of McClintock’s Franklin relics in the RNE Catalogue is merely a copy of the relics list from his book, The Voyage of the Fox. One can see this side by side: every paragraph, indent, and semicolon is just about identical.

{ McClintock relics lists: Voyage of the Fox (left) vs. RNE Catalogue. }

This makes every entry for McClintock relics in the RNE Catalogue somewhat untrustworthy; to be certain something was there, we ideally would want to see its presence corroborated in another source. That being said, I believe McClintock’s Franklin relics were held since 1859 at London’s RUSI Museum, of which one RNE organizer especially remarked that they had “stripped it to a gantline”:

“...everything that they possessed that was of interest to the Exhibition was freely lent to us by the Institution; in fact, I may say we stripped it to a gantline;”[Jephson 1892.]

The third issue to be aware of is that: there are multiple versions of the RNE Catalogue. I was unaware of this until I managed to obtain a copy, and saw that it was different from the (then) identical versions I had seen online. Afterwards I realized that Pieter van der Merwe had noted this in his 2001 article: “It [the RNE Catalogue] saw two editions.” However, I have since obtained a copy explicitly marked “Fourth Edition” — and, Alison Freebairn has even found reference to a 5th edition [Admiralty Library. Subject Catalogue of Printed Books. Part I. Historical Section. (1912), page 107).

I am here hosting PDFs of my two editions (1st and 4th, of the Franklin Gallery pages only). My earliest edition I believe to be the Catalogue’s 1st edition, though it is not explicitly marked so. The 2nd edition I believe is that commonly found online (its title page however lacking any ordinal designation). These first two editions both carry a Preface dated “May, 1891.” The 2nd edition adds a considerable number of items to the Franklin Gallery, and changes many of the item numbers. The 2nd edition can be distinguished from the 1st edition by the addition of item #13A on page 6 (or alternatively, by the highest Franklin Gallery item number reaching 197, instead of the 1st edition’s 178). The 3rd edition is available online, though rarer; it is marked “Third Edition” on its title page, and its Preface is dated “10th July, 1891.” The Victory Point cairn first appears in this 3rd edition (item #1A), consistent with newspaper notices announcing its debut in the month of July. The 4th edition is marked “Fourth Edition” on the title page, with a Preface dated “August, 1891”; its Franklin Gallery artifacts list seems to be identical to the 3rd edition.

Interestingly, a few items in the 1st edition seem to disappear from later editions. I believe #78, 126, 164, 170, and 171 are examples of this. Also, one Inglefield narwhal horn disappears from RNE #165 (in later editions as RNE #182).

Appendix 3: Full artifact identifications.

{ Reconstructed floor plan, with section codes. }

For clarity, I’ve created a naming scheme that divides the Franklin Gallery floor plan into three lateral sections: the North wall (N), the Central belt (C), and the South wall (S), using numbers for further subdivisions. For example: “C-2” (that is, Central section #2) is the Victory Point cairn.

All RNE Catalogue numbers are references to the 4th Edition (available for download in Appendix 2). [A reminder that numbers from the 1st edition of the RNE Catalogue will not match the following identifications.]

Section “S-1” I have reserved to refer to anything that may be unseen between the main doors (photo above) and the ice boat (photo below). We can not know what – if anything – is there, but it is a reasonable assumption that something might be. A number of objects listed as being in the Franklin Gallery are clearly not shown in any other section, and are therefore candidates to be in Section S-1 (listed here below).

Besides the above, the only other photograph we have into this section is an extremely distant shot taken from the far end of the Nelson Gallery (surviving at Greenwich’s NMM as photograph #ALB1386.12, and at Portsmouth’s NMRN as lantern slide RNM 1983/1238/32). I have not included the Greenwich or Portsmouth low resolution versions in this article, as purchasing the high resolution is a must to attempt to see the area (and which they do not permit to be published here). However, even at high resolution, neither image is especially helpful. [Click to see a low resolution version online of Greenwich’s photograph.] Curiously, the photograph shows a significant shadow through the arch, as opposed to the light from the entrance I had expected (and as is seen above that arch). It may therefore mean that Section S-1 had a short wall projecting out into the entrance area. It almost looks like we are seeing three paintings hung on such a wall. [Note: Vertical lines appear under the arch due to its collapsable Bostwick gate being closed, which at night sealed off the Nelson Gallery from the Franklin Gallery (Jephson 1892, page 556, Edye’s section). To clearly see two of these gates in their closed positions, near and far, refer to the manhaul sledging tableau lantern slide in this article.]

Lastly, I will note that: there are enough roof elements visible in other photographs that someone could potentially work out just how large this “S-1” section was. [The sizes of many of the identified objects in these photographs are known, and from these the size of the gallery could be extrapolated.]

The following objects – particularly the first one – may be in Section S-1:

#116: “Crow’s Nest.” This RNE item was sketched in the Aberdeen Weekly Journal, 6 May 1891 (see Appendix 1), and in The Queen, 30 May 1891. It was shown in the latter sketch with a shield on its mast. Given the nearby Nares relics in Section S-2 (the ice boat and ice saw) bearing similar shields, this Nares crow’s nest is likely nearby. An early visitor report in The Marine Engineer (1 May 1891) seems to confirm this. After touring the P&O pavilion, the Marine Engineer tour proceeds towards the main entrance area (misnaming the Franklin Gallery as the Howe): “Entering now the galleries we arrive at the point where the Howe and Seppings galleries converge near the main entrance from the Embankment. On our right is a magnificent trophy of arms... On our left is a stall representing H.M.S. Britannia, the school frigate for naval cadets. ... On the opposite side of the gallery, by the entrance to the Howe Gallery, there is a collection of Arctic exhibits—a figure in a “crow’s nest” fixed on the top of a mast confronts one.” It also seems likely that this is the same Nares crow’s nest that survives today at Greenwich (#AAA4312). Greenwich’s Nares crow’s nest has a mast, shield, and rope ladder still associated with it, the rope ladder in particular bearing a striking resemblance to The Queen’s sketch.

#127: “Tablet marked Observatory.” Seen sketched in Aberdeen Weekly Journal, 6 May 1891. This sign may be on the counter in Section S-4, with other pre-Franklin expedition material. However the sketch seen in Appendix 1 (from the Aberdeen Press & Journal, 6 May 1891) shows the sign on a pole, which if true might have made it too large to go up onto a counter display. [Link to Illuminator article on this relic.]

#2: “The Cape Riley Rake.” This Franklin relic – purportedly the first ever found – was an early motive for this study. I wanted to find a photograph of this relic for my 2020 article of the same name (link), and I knew it had been displayed at the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition. It was reportedly about 12 feet long (i.e., nearly as big as the ice saw), which ought to make it easy to spot. Six identified Franklin Gallery photographs later, I still have not found it.

Section S-2 is everything visible in Doug Wamsley’s lantern slide up to the Cloak Room door.

As noted in the main article, there is an ice saw on the wall, potentially a match for Greenwich’s ice saw #AAA4058 (link) and ice saw crossbar #AAA4042 (link). The ice saw has a shield on it, just visible over the gunwales of the boat (a similar one is on the boat itself).

The boat with sledge is almost certainly the “20 ft. Ice Boat with 12 man sleigh” listed in the Catalogue as RNE #116, “Articles used in the Expedition of 1875–76.” The shield with writing on the side starts with words similar to “20 ft. Ice Boat.” There are five lines of writing, the last two of which may be “in the Arctic Expedition” and “of 1875–6.” This boat-sledge is also a strong visual match for the “Ice Boat” seen sketched in The Queen, 30 May 1891, page 852 (and also in ILN, 29 May 1875, page 504).

The bird in the upper case behind the boat may be RNE #194 “Great Northern Diver” (a loon). The “little auk” included in #194 may be to the side of it here.

Section S-3 is everything between the Cloak Room door and the next door further down the gallery.

Presumably the kayak with mannequin is RNE #163, “A Kayak, complete with implements and dress,” as opposed to the simpler entry for RNE #164: “Kayak, completely fitted.” I do not know where the second kayak would be. There are at least two objects on the table in front of the kayak (which I can not identify).

As mentioned in the main article, the sledge to the left of the kayak is RNE #126, “Large Esquimaux Sledge, entirely of bone, brought home by Sir Ed. Parry,” as seen sketched in The Daily Graphic, 8 May 1891, page 5. There seems to be an informational shield resting on the left runner, similar to the two shields seen in section S-2. This is curious, as the other known shields in the Franklin Gallery (ice boat, ice saw, and crow’s nest) all seem to be associated with Nares relics; it raises the question of where the Nares relics were displayed previously, and if Parry’s bone sledge was perhaps there with them.

On the wall just above the sledge is a single frame displaying the first four sketches from A Series of Eight Sketches in Colour (1854) by Samuel Gurney Cresswell, corresponding to RNE #90 & 90A. [The popular one, Critical Position of HMS Investigator, is at the lower right.] The frame with the other four sketches must be obscured from our view by the dividing wall for the Cloak Room door.

Next to (but slightly taller than) that same wall, there appears to be a cabinet facing towards the Nelson Gallery. If the theme of section S-3 is Inuit culture, then this cabinet must be where the smaller Inuit artifacts were displayed, such as the models of kayaks and sledges (RNE #165, 166, 167, 168, 169). It is unfortunate that this cabinet is turned away from us.

Above this cabinet and above the Cresswell sketches is a row of three frames. Douglas Wamsley has identified the two outer frames as containing 13 of the 14 sketches from Walter May’s A Series of Fourteen Sketches, listed in the RNE Catalogue as #90 & 90A. [The one “missing,” curiously, is the sketch of Rae’s Franklin relics.]

On the wall closest to the Inuk in the kayak are five large uniform prints (forming an arch over three smaller frames). Douglas Wamsley has identified these larger prints as works by Edward Inglefield, listed in the RNE Catalogue as #63–67. Alone at the top is The perilous situation of H.M.S. Investigator while wintering in the pack in 1850–51 (RNE #63). In the middle row, on the left is H.M.S. Phoenix, Talbot and Diligence passing a remarkable iceberg (RNE #67), and on the right is H.M.S. Phoenix with her consorts, the Diligence and Breadalbane, among the ice-bergs off Disco (RNE #64). In the bottom row, on the left is Critical position of H.M.S. Phoenix, off Cape Riley, on the 18th of August, 1853, during the gale in which the gallant M. Bellot was drowned (RNE #65), and on the right is H.M.S. Phoenix and the Breadalbane at the moment when the latter was crushed and sunk (RNE #66). Wamsley notes that, as these identifications leave out only RNE #68 from the Catalogue’s group #63–68 marked together as being lent by Inglefield, then #68 (Isabel beset in Smith Sound) is likely to be the frame in the center of those hung on the wall. However, as of publishing we have been unable to find an image of the original to compare the RNE photograph to.

On the wall just beyond the Inuk in the kayak are three rows of five images. Douglas Wamsley has identified these as the chromo-lithographs by Edward Moss (RNE #88) seen in his 1878 book on the Nares expedition, Shores of the Polar Sea. Across the top row, the first can be identified as Back from the Farthest North (Plate 15), the middle as A Floeberg, Simmon’s Island (Plate 12), and the last as On the Northern March (Plate 8). In the second row, the second from the right is The “Alert” in Winter Quarters (Plate 10). In the bottom row, the middle image is The Last of the Paleocrystic Floe (Plate 16).

There are perhaps four narwhal tusks upright on the table in section S-3, with two at the extreme left (presumably from the same skull), and one behind the mannequin’s head. Kenn Harper advised me that the large object at the base of the central upright narwhal tusk is likely to be a narwhal skull/jaw, in which the tusk is still resting. RNE #182 says there were 8 total narwhal tusks in the gallery (two are in section C-3, holding up the sign); oddly the 1st edition RNE Catalogue said that there were 9.

There appear to be two sets of walrus tusks on the far end of the table, which could be part of RNE #183 or #187.

Not technically in this section, though seen in the photograph, is an object on the floor. Alexa Price guessed that this would be a Victorian fire extinguisher; as an example, she sent me a sketch of a Merryweather “hand fire-engine” of the period. We later saw in the RNE Catalogue that the same company seemed to have an exclusive contract: “Messrs. Merryweather & Sons have arranged with the Executive Committee that the whole of their Fire Engines and fire extinguishing apparatus shall be available for the extinction of fire, in the event of an outbreak occurring in the Exhibition buildings” (RNE Catalogue, #4051). A similar Merryweather model to this one — with the ring logo on the side — sold at the auction site Ebay in 2014 (link to sale). There appears to be another Franklin Gallery fire extinguisher beneath the oval portrait of James Clark Ross (in section N-2). More Merryweather fire equipment can be seen in the Howe Gallery lantern slide in this article.

{ Section S-4. }

Section S-4: ‘Willoughby.’

As mentioned in the main article, the first painting is Sir Hugh Willoughby, RNE #25.

At the very end of the section, on the dividing wall, is a landscape painting that can be observed more effectively in wider photographs (i.e., not lantern slides) of the sledging tableau.

{ Sections C-1, C-2 (missing), and C-3. }

Section C-1: ‘Polar Spirit.’

Section C-2: ‘Victory Point Cairn.’

Section C-3: ‘Victory Point Record.’

Section C-1 is the statue The Polar Spirit by Ferdinand Junck (RNE #1). Section C-2 is the Victory Point cairn model (RNE #1A, “Representation of the Cairn in which the Franklin Record was found”).

As argued in the main article, the Victory Point Record (RNE #22) is in the central glass case of section C-3. Above is a custom sign for the Franklin Gallery, beginning with the words “These Sad Relics;” as identified by Alison Freebairn, it is a match for artifact #AAB0506 (link) at Greenwich’s National Maritime Museum. The sign is held up by two narwhal tusks. It should here be questioned if the sign was actually custom-made for the RNE, given that nothing on it indicates that it was. It could be similar to three shields in the Franklin Gallery, each associated with Nares relics, suggesting that they were perhaps created for wherever the Nares relics were previously displayed (see the point about this in Section S-3). Similarly, the ‘These Sad Relics’ sign could have hung above the Franklin relics at the RUSI Museum since that exhibit opened in 1859. In this sense, the point about General Gordon is worth revisiting: associating a quote by Gordon with Franklin strongly suggests a creation date after 1885, and that suggests that the sign was indeed custom-made for the 1891 Franklin Gallery.

I believe the large upright silhouette underneath the display is the stove returned from Victory Point by the Schwatka search. I discuss this in an annex to this article: “A Silhouette in the 1891 Franklin Gallery” (link).

Hanging from the ceiling above section C-3 is RNE #121, “Arctic Balloon.” It is a match for the sketch in The Queen, 30 May 1891. It may be the same object as Greenwich’s #AAA4347 (link); the name Shepherd is attached to both. The pieces hanging beneath the balloon in the RNE photograph would then be included in Greenwich’s #AAA4347.2 (link): “...including the balloon net, rubber tube, various lengths of red ribbon, facsimile messages and white tape from inside the balloon.” [Update 2024: On 26 January 2023, Michael Suever sent me his prior research connecting the RNE balloon to the balloon at Greenwich today. In ADM 169/427 at the National Archives are receipts showing that in September 1914, Herbert E. Shepherd donated the “only existing” Franklin search balloon to Greenwich Hospital. The records state that this had once been “Exhibited at the Ryl Naval Exhibition 1891.” The same artifact is then transferred to the Royal Naval Museum in 1920.]

Prior to seeing the sketch of this exhibit in The Queen (30 May 1891), I thought that Doug Wamsley’s photograph seemed to show one of the Boat Place shotguns upright behind the Victory Point Record. The Queen’s sketch seems to confirm and expand on this, showing a tripod appearing to consist of a paddle handle and both Boat Place double-barreled guns, #AAA2531 (link) and #AAA2612 (link).

Sitting atop the flat cases on the right of the exhibit is a small glass domed display. In the sketch in The Queen (30 May 1891), this almost looks as though it may be Hornby’s sextant (#AAA2230, stolen from Greenwich in 1982; see my October 2020 article “Cheyne’s Relics” for a photograph). Beyond and partially obscured by this domed display is a very long artifact (propped up by a taller display in back); it may be the boat stem recovered by Schwatka at the Erebus Bay ‘Boat Place,’ however even this limited amount of detail does not seem to match that object.

The Queen sketch (30 May 1891) shows a sledge flag with letters, and at the base of the flags cabinet are the letters, “ED IN THE.” What these refer to has not yet been determined.

Section C-4: ‘Sledging.’

Sources identified this manhaul sledging exhibit as consisting entirely of Nares expedition equipment (RNE Lantern Readings; Stead 1891). [Note: I thought I once saw a reference to a sledge here being “a McClintock sledge.” This may have meant the construction style not the expedition origin. If anyone runs across this, please contact me.]

At high resolution, the flag flying from the sledge can be identified as Albert Markham’s motto flag, with the words “Luctor et Emergo” legible. It can be seen sketched in The Geographical Magazine (1 Dec 1876, Volume 3, near page 320, “The Five Flags Hoisted At...”), and was apparently blue with a blue and yellow alternating fringe. [Update 2024: This article originally misidentified the motto flag as belonging to George Nares; in January 2024, Claire Warrior caught the error and contacted me.]

Four of the five manhauling mannequins have smocks with visible cartoons on the back; none have yet been identified. Update 2024: Alex Cross from St Helens, Merseyside, has identified the leader of the team as wearing Smock AAA3985 at Greenwich’s NMM; previously catalogued as an 1857 smock belonging to McClintock, AAA3985 ought to be reconsidered as an 1870s Nares Expedition smock donated by McClintock’s descendants.